Sex Workers Mobilise Against ‘Dangerous’ Bill Set to Criminalise Clients

by Sophie K Rosa

11 December 2020

Parliament has passed a controversial bill proposing the UK adopts the ‘Nordic model’ for its laws on sex work. The bill, brought by Labour MP Diana Johnson on Wednesday, is opposed by sex workers and groups including Amnesty International, harm-reduction charity Release and Women Against Rape, who argue that the legal model it proposes is driven by ideology, not evidence and puts workers’ lives at risk.

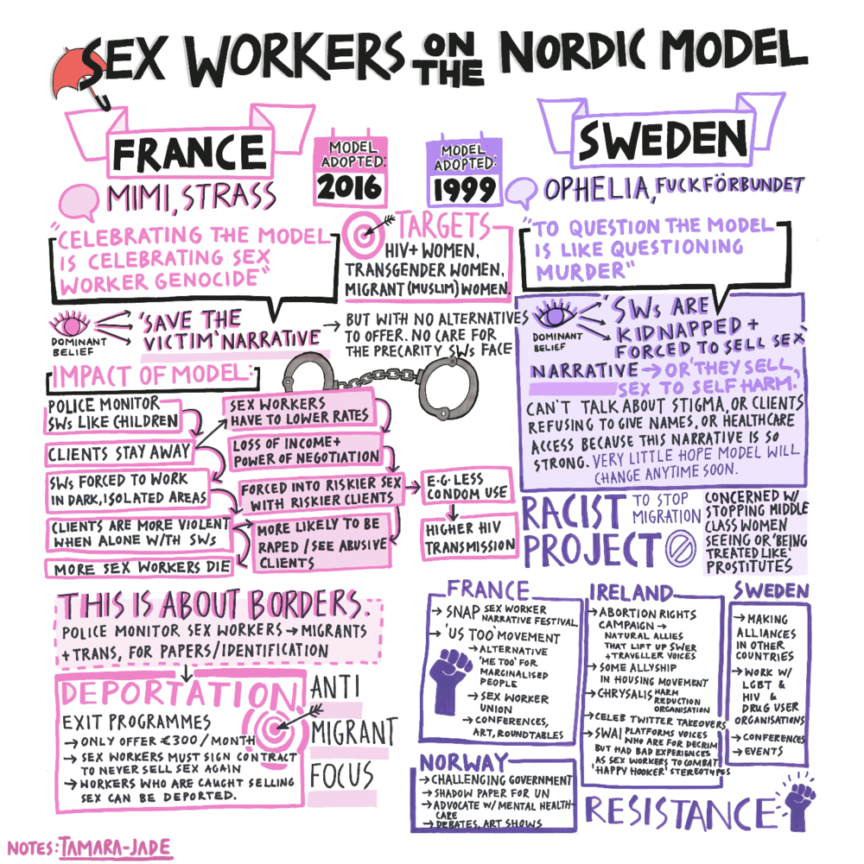

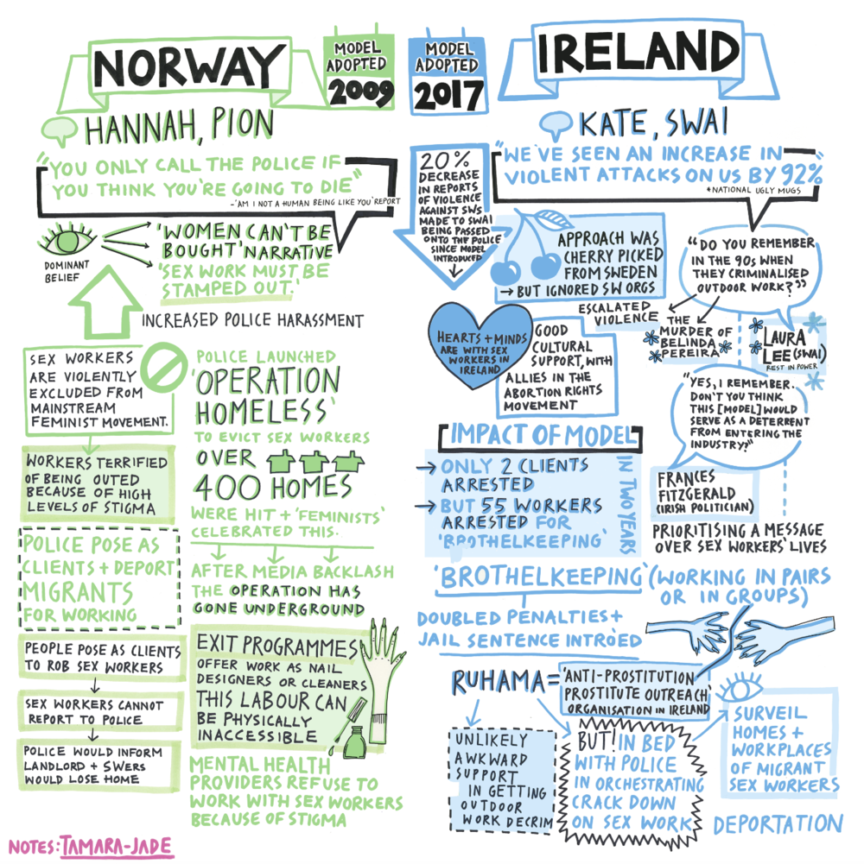

Johnson’s bill – co-signed by Labour MPs including Stella Creasy, Sarah Champion and Rosie Duffield, and opposed by Labour MP Lyn Brown – would criminalise paying for sex and decriminalise selling sex, imposing what is known as the ‘Nordic’ or ‘end demand’ model. This legal model, currently in place in Sweden, Norway, Iceland, France, Ireland, Northern Ireland and Canada, has been met with resistance from sex workers since its inception in 1999.

In theory, the Nordic model criminalises clients and third parties in the sex trade, leaving workers unharmed, whilst supporting them to leave the industry. However, evidence from countries where it is enforced shows that it has created more dangerous working conditions, whilst still criminalising workers and not supporting exit for those who want to leave the industry.

By criminalising paying for sex, Johnson’s bill would shrink sex workers’ client pool, leaving them with less freedom to turn down clients. “What other laws are [these remaining clients] willing to break?” asks Sarah, an organiser for sex workers’ rights campaign Decrim Now and a member of her local Labour party branch, referring to the increased rates of violence that workers living under the Nordic model experience.

“If you criminalise a client, they get to set the terms of how you sell sex,” she explains. A client who is risking arrest is more likely to insist a worker enters a car in a rush, or that they meet in an unsafe, unfamiliar place. Reduced demand means workers have to minimise their screening processes and accept clients they otherwise wouldn’t, as well as lower their prices.

Compelling speech today by @lynbrownmp against a dangerous 10-Minute Rule motion which would criminalise sex workers clients saying it “will put women at greater risk”. #MakeAllWomenSafe https://t.co/XN1LU5PmKn pic.twitter.com/t1UrrCfGuI

— English Collective of Prostitutes ♀️ ⚧️ (@ProstitutesColl) December 9, 2020

A report by Medicins du Monde found that since the introduction of the ‘end demand’ model in France, “violence, of all kinds have increased: insults in the street, physical violence, sexual violence, theft, and armed robbery in the workplace.”

The report also found that the laws “had a detrimental effect on sex workers’ safety, health and overall living conditions,” and “increased impoverishment, especially among people already living precariously, namely undocumented migrant women working in the street.”

“The people who are most affected by the Nordic model are the people with fewest choices,” says Sarah. “They’re having their income source taken away and they don’t have any way to replace it, so they are going to take more risks because they are working in such precarious conditions, which is what we see for precarious workers all over the world.”

aYou will often hear “well sex work can’t be work, you don’t need exit programmes for other work”. Well, here’s the thing, many workers in many industries are trapped in exploitative conditions, abusive workplaces, stressed, bullied, the exit programme should be the welfare state.

— Em (@grumpyhooker) December 10, 2020

The bill would also criminalise what Johnson calls “pimping sites,” which are in fact websites mostly used by sex workers themselves to independently find and screen clients without relying on exploitative third-parties and managers. “Online advertising has been proven to give sex workers more power,” says Sarah, adding that this part of the bill would also prevent sex workers from collectively organising to create their own online platforms.

Niki Adams from the English Collective of Prostitutes believes Johnson’s bill represents a harmful anti-sex work ideology – more concerned with eradicating the industry on moral grounds than improving women’s material conditions – which has “traditionally been led by an unholy alliance of feminist politicians and fundamentalist Christians.” In Northern Ireland, Adam explains, “it was the reactionary, homophobic, anti-abortion Lord Morrow, who, backed by feminist campaigners, put forward the Human Trafficking and Exploitation Bill,” which criminalised clients.

Indeed, Johnson’s speech in parliament to propose the bill, repeatedly referred to “trafficking” and “exploitation”, failing to draw any distinctions between forced labour, trafficked labour and consensual sex work, and without considering how women’s material conditions mean they may choose to cross borders or to do sex work.

“The justification for this bill is that trafficking is rife and can be reduced if sex workers’ clients are criminalized. This is untrue,” says Adams. In fact, she says, “trafficking is enabled by poverty and women’s need and determination to escape it,” as well as “the hostile immigration environment that makes it impossible for most migrants to cross international borders unaided.” Anti-trafficking laws already exist in the UK, and in practice, they “have been used as a justification for police crackdowns which have targeted migrant sex workers for arrest and deportation and have distorted the public perception of how much prostitution is directly the result of trafficking,” says Adams.

The proposed bill also fails to address the most pressing reasons why women do sex work: to earn enough money to survive and care for their children. Adams says that Nordic model proponent ‘feminists’ “target prostitution as uniquely degrading, seemingly oblivious to the degradation and humiliation women face having to skip meals, beg, or submit to a violent partner to keep a roof over their heads.”

The Covid-19 pandemic has seen more women enter sex work, whilst the client base as shrunk – workers report that poverty and violence at work have both risen.

Just saying that we’ve seen what happens to sex workers with a loss of demand for their work due to the pandemic and it’s been terrible, actually

— Lydia Caradonna 💥 (@LydiaCaradonna) December 9, 2020

London-based sex worker Anna* says that she and other sex workers have been faced with more dangerous clients this year. National Ugly Mugs, an anti-violence organisation where sex workers can report incidents, sends text alerts to workers, and Anna says that in the past 24 hours alone she has received messages about “workers being robbed at gunpoint” and raped. “It’s already dangerous,” she says, “and I’m scared about how much worse things will get if this bill is brought into law.”

Anna is also concerned about the impact of the economic fallout from Brexit on sex workers. Because of a lack of other job options and insufficient state support, more women are likely to enter sex work. In this context, the bill feels like “suffocation” and seems to be saying to workers that “we don’t care about your safety,” Anna says.

Just can’t believe how vile it is to do this to us during a pandemic. At a time of incoming economic doom where even more ppl will be pushed into sex work. This bill is murder.

— Fez (@fendalaust) December 9, 2020

Johnson quoted clients’ negative online reviews of sex workers in her speech and referred to “women being raped and abused for profit,” seemingly to invoke outrage against the sex industry on moral, ‘feminist’ grounds. Sarah believes such rhetoric erases sex workers lived experiences and positions them as “disposable collateral damage in some war to punish ‘bad men’.”

“No sex worker I know has that much sympathy for clients,” she says, “but those supporting Johnson’s bill shouldn’t be letting their anger at clients override the need for sex workers to work in safety; criminalisation of women’s incomes and workplaces will not stop men from writing abusive things about women on the internet.”

Anna, who is a United Sex Workers trade union member, wants politicians to heed workers’ demands. “It just makes me angry that people who have no idea what it’s like to do sex work are making decisions that will endanger me and people I love.” She says politicians should “listen to workers” who “know what we need to feel safe”, along with the views of rights and health organisations like Amnesty International, the World Health Organisation, Human Rights Watch, all of which support decriminalisation of the entire sex industry.

I do feel physically sick, it’s already the worst year from my career, we already saw an increase on violence and bad clients during the pandemic, imposing the NM and banning advertising website is extremely harmful, I am fearful for my future https://t.co/ITDgO2MnSA

— Vana (@VanaM124) December 9, 2020

Sex worker activists and allies are calling for people to email their MPs and tell them to oppose the bill, which will have its second reading on 29 January 2021. “Labour members and MPs who claim to be concerned about abuse and violence against women, should back sex worker-led struggles for labour rights,” says Adams, instead of supporting a bill that “will increase violence against sex workers and increase the powers of the police against a criminalised sector of women.”

As sex workers mobilise to fight this bill, Sarah believes that “solidarity across different groups who are also penalised by the state,” is crucial. “It’s really important we don’t ‘other’ sex workers,” she says. “Sex workers’ struggles are migrant struggles; are women’s struggles; are mothers’ struggles; are disabled peoples struggles.”

“Pro-criminalisation ‘feminists’ within the establishment do not represent us,” adds Adams. “Their choice to side with the state and increase police powers against us, whilst standing by as we are made poorer and more vulnerable to violence, is no real feminism at all.”

*Identifying details have been changed to protect anonymity.

Graphics by Tamara Jade.

Sophie K Rosa is a freelance journalist. In addition to Novara Media, she writes for the Guardian, VICE, Open Democracy, CNN, Al Jazeera and Buzzfeed.