If Jews Don’t Count As an Ethnic Minority, It’s Because We Haven’t Always Wanted To

Only recently has ethnic minority status become covetable. British Jews have spent much of our history avoiding it.

by Joseph Finlay

22 March 2021

Only in recent years has ethnic minority status become something people might adopt out of choice rather than assignation. British Jews have spent much of their history avoiding it.

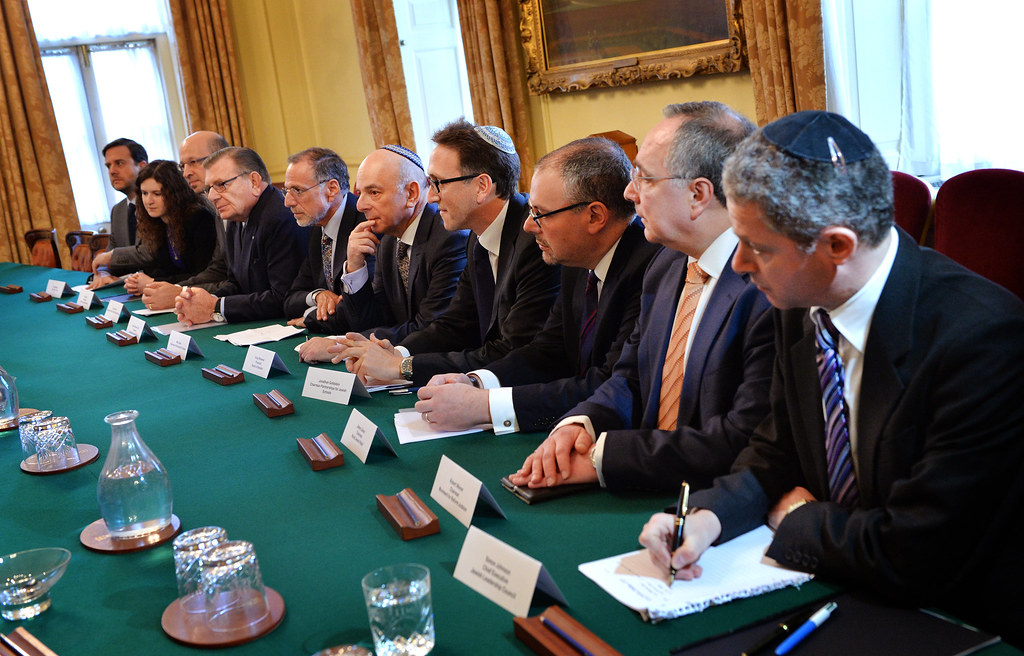

When Anas Sarwar, the newly-elected leader of Scottish Labour, declared himself the first-ever ethnic minority leader of a political party in the UK, he probably didn’t envisage the furore that would ensue. Pointing to Michael Howard, Ed Miliband and even Benjamin Disraeli (no one remembered poor Herbert Samuel, Liberal party leader from 1931 to 1935), Jewish leaders insisted that Sarwar’s statement was further evidence of the fact that, to quote David Baddiel, Jews don’t count. Yet if there is any popular confusion over whether British Jews are an ethnic minority it’s because, for most of their history, they did not wish to be.

Categories of identity are socially constructed and liable to change over time, so anyone expecting a definitive answer to what Jews are is likely to be disappointed. Over time, we have presented ourselves as a race, an ethnicity, a people and a nation, but most commonly, at least when talking to the outside world, as a religion. This has had a key social advantage. By presenting ourselves as members of the Jewish faith, or “Englishmen of the Mosaic persuasion”, Jews could assimilate into Britishness while maintaining a distinct cultural identity. With the important exceptions of Jews from North Africa, the Middle East and India, Jews could be treated as largely white, Jewish difference like that of non-conforming Christian denominations such as Methodists or Quakers. Hence why many Anglo-Jewish institutions, such as the United Synagogue and Chief Rabbinate, are modelled on the Church of England, and why a range of British laws, including those regulating marriages, refer to “persons professing the Jewish religion”.

Of course, there were always antisemites who saw Jews in racial terms, insisting that Jews who converted to Christianity or no longer defined themselves as Jewish were Jews, whether they liked it or not. But this racial identity was, in the main, imposed from without. Antisemitism was distinguished from older forms of anti-Jewish hatred by its foundation in race science; Nazis treated Jews as a race, persecuting them regardless of religious practice. This did not mean Jews accepted their racialisation; indeed, most Jews saw it as a hostile and oppressive categorisation, and Jewish intellectuals played a major role in discrediting race theory in the years after the second world war.

As recently as the 1960s, Jews insisted on themselves as a religious rather than a racial group. In the lead-up to the 1965 Race Relations Act, British Jewish leaders (unsuccessfully) pressed the government for the inclusion of religion – partly because they feared that antisemites would use its absence as a loophole for continuing to attack Jews, but also because of their unhappiness at Jews being labelled a racial or ethnic group. A 1969 Board of Deputies report on race relations presented Jews as a group that could offer help to racialised groups, rather than a racial group in itself.

The primary evidence for Jews being considered an ethnic minority is a 1983 House of Lords ruling which found that, while not protected as a religion, Sikhs could be protected under the Race Relations Act as an ethnic group, citing Jews as a similar example. But the ruling did not define Jews as an ethnic minority for all purposes; it simply meant that Jews could be considered one for the purposes of prosecuting hate crime.

In the 1980s, the British state used the language of “minority ethnic” to summarise Britain’s non-white population, which it was increasingly keen to treat as a whole. Scholarship and official documentation did not put Jews in this category, nor any white European groups living in Britain. In parallel, radical activists created the language of political Blackness as an umbrella term to unite those racialised by the British state. Most Jews – barring a small number of Jews of colour, like the Indian-Jewish radical Shalom Charikar – eschewed it. BME and BAME (terms that have always been used as shorthand for non-white) are the ungainly and unloved inheritors of this era; until very recently, few Jews have used them.

British Jewish leaders strongly opposed the inclusion of a race and ethnicity question on the census in the 1980s, partly on the grounds that Jewish identity was multi-faceted and not simply ethnic, and partly because of memories of Nazi use of Jewish lists in the Holocaust. When ethnicity was added to the census in 1991, “Jewish” was not an option; the Board of Deputies recommended that the vast majority of British Jews should tick “white”. By contrast, Jewish leaders were happy with the inclusion of “Jewish” as one of the given answers for the religion question, first introduced in 2001.

Making Jewish a category in the ethnicity question was once again rejected by the Office for National Statistics for this year’s census, for reasons similar to those of the 1980s: “References to Jewishness as an ethnicity,” concluded an external body after conducting focus groups, “evoked comparisons to the discrimination and persecution suffered by Jewish people over the last century.” Those in the focus groups did not see their Jewishness as ethnic, and felt that to include a Jewish ethnicity would be to “single out” Jews – exactly the reverse of current complaints.

In the 1980s some Jewish activists, particularly within the Jewish Socialist Group and the Union of Jewish Students, began to argue that Jews should portray themselves as an ethnic minority. But the idea really developed in the New Labour period, as, at least in the early years of the Blair era, multiculturalism became, for the first time, a state-sanctioned discourse. This coincided with a period of very close relations between the government and Jewish leaders, marked by the creation in 2001 of Holocaust Memorial Day. In the 2001 census, around 5% of Jewish respondents wrote in “Jewish” as their ethnicity; by 2011, that had increased to around 12%. But the development was still limited: in 2006, speaking in Bevis Marks Synagogue to mark 350 years since the readmission of Jews to England, Tony Blair described British Jews as “the oldest minority faith community in this country” who showed that “faith can be combined with a deep loyalty to our nation”.

If some British Jews now wish to define their Jewishness as ethnicity, they have every right to do so, but given the recent shift that this reflects, wider society can hardly be blamed for struggling to keep up. Until very recently, it made no sense for Jews to claim ethnic minority status; to do so would have constituted a social demotion. The recent reversal seems to be based in a questionable belief that the opposite is now the case.

Much of British Jews’ newfound desire to be categorised as ethnic has been motivated by an erroneous belief that “no other minority would be treated this way”; that racism towards Black and Asian people is taken more seriously than anti-Jewish prejudice. In fact, the reverse is true: antisemitism is treated more seriously than other racisms as a result of the model minority status the British state has increasingly assigned to Jews since the 1980s. This state philosemitism, as Alana Lentin has argued, implicitly positions Jews as aligned with the interests of the state and with whiteness. A new ethnocultural understanding of Jewish identity for the 21st century is possible, but we need to recognise its implications. Such a Jewishness would resist philosemitism and assimilation into whiteness. It would necessitate a distancing from the institutions of the British state, and a greater affinity with other racialised groups. It may be a move worth making. Perhaps it’s time to become Jews of the British persuasion.

Joseph Finlay is a historian of British Jews and race relations in postwar Britain.