Bombers in Paris: The Arrest of Italy’s ‘Red Terrorists’ Raises the Spectre of Political Violence

Decades after Italy’s ‘years of lead’, the left still has questions to reckon with.

by James Butler

28 April 2021

In Paris this morning, seven Italians were arrested, all former members of ‘red terrorist’ groups – small groups of clandestine militants who carried out kidnappings, bombings and assassinations during Italy’s ‘years of lead’. All seven were long ago convicted in their absence by Italian courts, on charges varying from murder to armed robbery; three further ex-terrorists evaded capture by the French authorities. They await a judicial hearing on extradition to Italy, and it is widely expected that extradition will be granted. Italian prime minister Mario Draghi declared that the “terrorist crimes” remained an “open wound” in Italian memory, and welcomed their extradition.

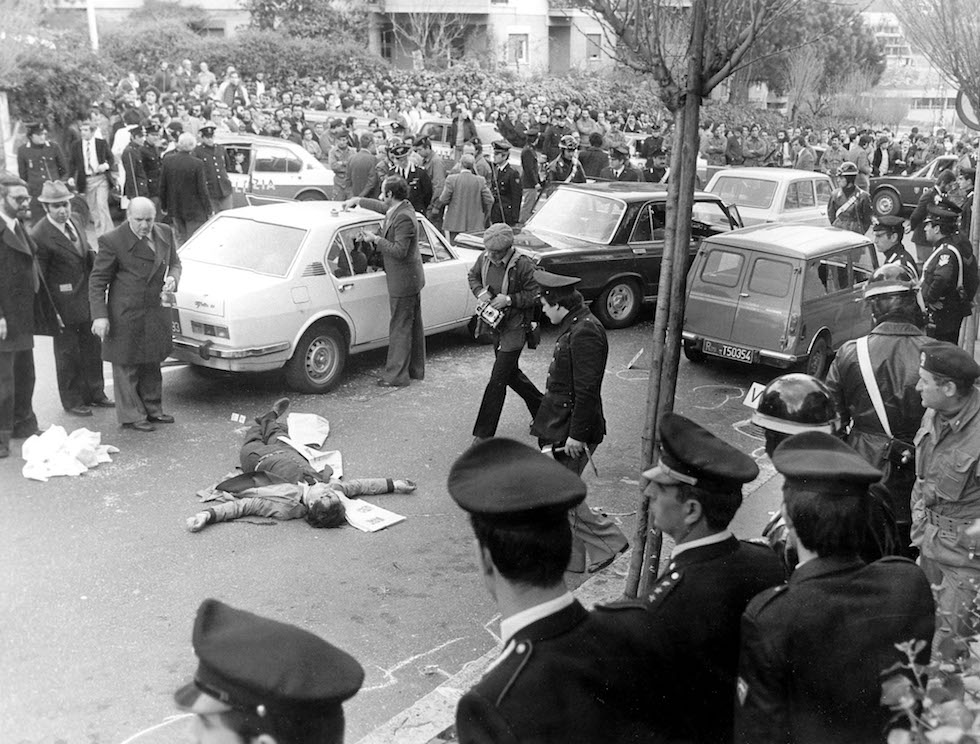

The ‘years of lead’ were a roughly two-decade period of undeclared and semi-clandestine civil war in Italy, between the late 1960s and late 1980s, involving three parties: the Italian state, far-right neofascist groups, and the far left. Contact between the Italian security state and the far right was common, and included an abortive coup attempt in 1970. The period gave us the phrase ‘strategy of tension’, where acts of violence are tacitly or explicitly encouraged by those in power in order to enable a crackdown; the ‘years of lead’ are so-called because of the countless bullets fired in that time. Leftwing armed groups emerged from a strong extra-parliamentary movement, drawing from the factory militancy of the late 1960s, as well as youth and student organisations, often articulated against the staid and conservative politics of official Communism. Violence was common at demonstrations, even for those who did not make the transition into the small armed groups; those who did would often cite fear of a coup, unpunished and uninvestigated murders of leftwing activists, or the fascist bombing at Piazza Fontana as prompting their decision to take up arms. Some – though fewer in hindsight than claimed it at the time – believed simply it was the only possible route for change in a corrupt and blocked political system.

The Red Brigades were the most notorious of the armed groups, though there were many others. Though newspaper reports have declared that seven brigatisti have been arrested, in fact only four of the arrestees are former members. The Brigades have come to stand for the entirety of the armed struggle because they were authors of its most noxious crime: the kidnapping and murder of former Christian Democrat (DC) prime minister Aldo Moro. Moro was targeted because he had engineered the ‘historic compromise’, an agreement which brought the Italian Communist party (PCI) into a confidence arrangement with the DC. The Brigades held him hostage, but, unable to extract concessions from the government, murdered him in May 1978, dumping his body near the headquarters of both parties. Many areas of the Moro Affair remain murky, including the responses of both government and police, apparently unable to find Moro under their noses in Rome. The Brigades’ own communiqués are an arid mix of thought-terminating jargon, self-justifying delusion and ethical mutilation; the Moro killing became a means to poison the reputation of the entire Italian left, and the pretext for the destruction of an entire political movement, well beyond the armed groups (40,000 accused, 15,000 passed through prison, 6,000 sentenced, as author Nanni Balestrini put it in the preface to a history of the movement).

It is this wave of repression which explains why so many former red guerrillas have been in France for the past forty years. The Italian crackdown made a parody of due process, often operating on conspiracy theories propounded by prosecutors like Padua’s Pietro Calogero, who believed that intra-left polemicising was a ploy to conceal a secret web of Red Brigades leaders, including prominent left theorists and academics such as Antonio Negri. Trials, when they happened at all, relied on the testimony of pentiti – cooperative former militants, often with an eye to a reduced sentence – whose stories were not always coherent. (Negri’s own accuser fled the country on a passport provided by the Italian secret service.) The pentiti were often objects of scorn, even among those who renounced armed struggle: one such repentant militant, Arrigo Cavallina, endured years in prison declaring himself “unwilling to prove this change by turning into a merchant of human flesh”.

These legal irregularities led to a commitment in 1985 by then French president François Mitterrand to refuse to extradite red terrorists who were not guilty of “crimes of blood” to Italy: this ‘Mitterrand doctrine’, though formally renounced by Jacques Chirac in 2002, has remained the de facto position of the French state since. Sources close to Emmanuel Macron have briefed widely that they are only applying the doctrine – with its specific reference to “crimes of blood” – but the move also comes after increasing pressure from the Italian right. During his tenure as interior minister, Matteo Salvini often made reference to France leaving “terrorists who massacred Italians […] free to drink champagne”. Irene Terrel, the French lawyer who became prominent defending previous extradition attempts, has thus far simply dubbed the arrests “outrageous”, stressing that they come after those concerned have remade their lives, “40 years after the facts”.

The Italy of the ‘years of lead’ has largely disappeared, its parties collapsing in the wake of the enormous Tangentopoli bribery scandal of the early 1990s, and its violence and paranoia – or even the mere fact of those two decades of political conflict – are less frequently remembered in the rest of Europe than they should be. Contrary to Draghi’s statement, many Italians, of all political stripes, prefer to leave a veil of silence around the period. The weakness of Terrel’s statement – simply, that it has been a long time – perhaps also suggests the awkwardness of these arrests for some on the left. The enormous international campaign against the iniquities of the Italian state and its corrupt judicial system in the 1970s and 1980s was undoubtedly justified, but often relied on a studied ambiguity about political violence itself – sometimes even tilting towards the crude enthusiasm of the scholar or writer for the man of action. But the question of political violence cannot today be reduced to a second order concern, nor can it be ascribed purely to external circumstances, even if it is stressed that it was practiced by the far right and the state as well. The Communist journalist Rossana Rossanda provoked much outrage on her own side when she suggested the left must think of the Red Brigades as part of its “family album”, but her argument – that unless insurrectionary violence is understood as one possible expression of a leftwing politics, however deformed, its internal logic cannot be understood or altered – is much more fruitful than simply disclaiming that aspect of the left’s history. Without a compelling account of political violence it is impossible to combat the lie that the trajectory from the first worker downing tools in Mirafiori in 1968 to the bullet that killed Aldo Moro was an inevitable one. Or as Balestrini put that political choice in one of his most penetrating novels of the period:

“… we maintained it was madness to decide in the name of the movement on a leap into clandestinity with one stroke to wipe out everything that had been achieved so far to abandon a movement of thousands of people in a struggle for a war waged by twenty or thirty.”

James Butler is Novara Media’s co-founder and head of audio.