‘How Can I Use This, Rather Than It Use Me?’ A New Campaign Takes Aim at Screen Addiction

Last year the average person spent 40% of their waking hours on a phone, TV or laptop.

by Sophie K Rosa

6 May 2021

“I logged into this thing, typed into the chatbox – ‘hello’ – and somebody in America typed ‘hello’ back,” recalls writer Julia Bell of using her friend’s computer in the early nineties. “I screamed,” she says, “I was like, ‘oh my fucking god, it speaks back – this thing speaks back to me!’”

Three decades on, most of us live cyborg-like lives, with the myriad functions of computers and smartphones having become pervasive and apparently vital to almost all aspects of our existence.

This Thursday, Bell, the author of Radical Attention, is speaking at the launch event of Screen Burn, a new research and campaigning organisation looking at excessive screen use and screen addiction.

Joe Ryle, co-founder of Screen Burn, says the organisation is the first of its kind. “There’s literally nothing [like Screen Burn] in the UK,” he says, “which is shocking really because [screen use] is such a big issue […] and it’s been such a quick change to screens everywhere, all the time.” Whilst attentive to the many important benefits of digital technology, Ryle and the co-founders of Screen Burn believe there is an urgent need for more awareness, research, campaigning and regulation around the impact of excessive screen time and addiction.

“We think it’s having all kinds of negative side effects in terms of mental health, destroying our attention, causing our brains to be in a constant state of distraction,” he says. “All of these things would suggest that screen overuse [and] addiction should be seen as a public health issue.”

Start your digital detox today! You can start with a small change such as switching off notifications and blocking your fave apps and sites for a few hours a day. pic.twitter.com/3Gpwp2VquP

— Screen Burn (@screenburn2021) April 26, 2021

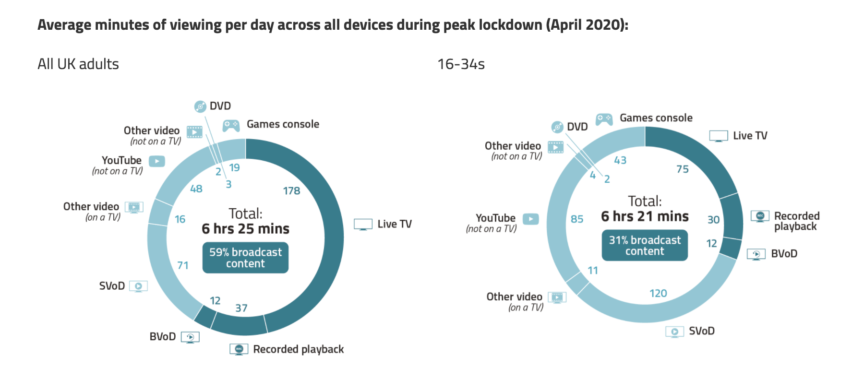

Last year, watchdog Ofcom found that UK adults spent on average 40% of their waking hours – six hours and 25 minutes – on phones, TVs and laptops. This pandemic-year figure was a third higher than the year before.

Bell is concerned we have sleepwalked into submission at the hands of tech giants with little-to-no concern for our wellbeing. When scrolling a social media feed, hours can pass like minutes, she observes, because “the behaviourists in Silicon Valley know very well the things that are going to trigger you to keep scrolling and keep looking”. The way that social media algorithms hook and retain our attention for profit, she says, distorts our temporal reality, “robbing us of a future”.

Boe Huntress, an artist who co-founded Screen Burn with Ryle, began evaluating her own relationship with screens when she realised that focussing on the work she enjoys – making music and writing – had become increasingly difficult. “Ten years ago,” she says “I would very often get into what people call a ‘flow state’, where you’re so absorbed in what you’re doing that time sort of changes.” The rising dominance of screens has meant that now she finds herself “constantly being distracted”. Even if she turns all her screens off whilst she works, she says, her attention feels “fragmented”. Reading into the topic, she found that research shows that screen time can have long-term impacts on cognitive function, including attention span and memory.

Huntress is now committed to limiting her screen time and runs courses – affiliated with Screen Burn – to help others do the same. People attending the workshops, she says, are often worried about the impact screen time is having on their mental health. They are usually “struggling with productivity, with focus, with attention span, with feeling quite muddled generally,” she says, and concerned about the impact screen time is having on their overall wellbeing – including social skills, sleep and relationships.

Whether because of work or social ties, our screens can invoke “a feeling of needing to be constantly available, constantly ‘on’,” she says, which can leave people feeling “anxious and overwhelmed”. Often, people experience phones especially as an addiction: turning to them for a dopamine hit, then feeling worse and even ashamed. “It just becomes this spiral,” she says.

Digital devices and social media platforms are “designed by the tech companies to be addictive,” says Ryle, “a lot of people don’t realise that.” The longer we are on our screens, the more they profit.

When we scroll and create content on social media platforms, says Bell, we would do well to remember we are generating profit for the company in question. She is concerned, in this sense, about the “commercialisation of socialising”, “curating your public persona” online, and “the commodification of the mind” – when our passing thoughts are “being turned into something that has monetary value.”

On one occasion, Bell recalls, she shared a video about transphobia on Facebook. The algorithm, having judged her ‘interests’, began showing her transphobic content. Social media companies’ profit-driven algorithms “don’t care about whether or not trans people get beaten up on the bus”, she says, they’re designed to get “loads of clicks, and therefore more revenue”. As well as having potentially devastating impacts on our everyday existence, the saturation of screens is related to the entrenchment of “structural inequality” and the disturbance of the democratic process – for example, the impact of viral fake news on the election of Donald Trump.

Reflecting upon the prominence of screens in our lives, then, is in large part about taking back control of our lives from big tech, and demanding system-level change. “Of course smartphones and screens do bring massive benefits to society, but we’ve forgotten to think about some of the negative side effects,” says Ryle, since “a relatively new trend” has “exploded […] with basically no checks and balances in place”. Now, he believes, it is time that our resistance to the negative aspects of this “catch[es] up”. As an organisation, Screen Burn hopes to build conversations and knowledge around excessive screen use and addiction, and campaign for more guidance and regulation on ethical and public health grounds. For example, through the implementation of ‘right to disconnect’ laws, and governments holding tech companies to account for their impact on people’s wellbeing and safety.

And on a personal level, with the pandemic having exposed most of us to the impacts of unprecedented screen time, people may well be ready to rethink their relationship to digital technology. Bell believes there is “a growing awareness in the individual that actually [excessive screen time and social media] is kind of rotting my head.” The question for all of us, she proposes, is: “How can I use this, rather than it use me?”

Sophie K Rosa is a freelance journalist. In addition to Novara Media, she writes for the Guardian, VICE, Open Democracy, CNN, Al Jazeera and Buzzfeed.