After Big Losses, Labour Must Change Tack or Risk Irrelevancy

The Labour party must change path if it is ever to form a government again.

by James Meadway

13 May 2021

The Labour party suffered an embarrassing defeat in last week’s local elections – there’s no way to sugar coat that fact. Losing Hartlepool to the Tories – a Labour seat since its creation in 1974 – going backwards in Scotland and losing control of councils in the north added up to a grim night for the party. That said, the bigger challenge for Labour now is not just having to stem and reverse its losses, but finding a way to relate to its new and emerging supporters.

The shift in Labour’s historic suppoter base – from the loss of voters in its heartlands, to the gain of surprising new patches of voters in areas like Worthing in Sussex – poses huge problems for a party that is historically rather bad at executing the deft changes in direction necessary to reclaim power – something that the Conservatives have excelled at for over a century.

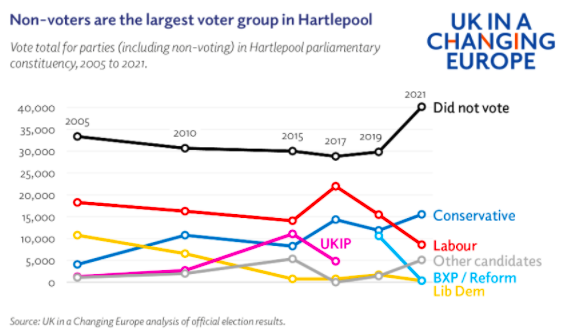

The result in Hartlepool dominated the news as the scale of Labour’s defeat became apparent. In a dramatic upset, the Tories won a majority of almost 7,000 votes on a 23% swing. But whilst much commentary has attributed this to a straight switch of voters from Labour to Conservatives, the real driver behind the Hartlepool result can be seen in the graph below:

Allowing for the fact that this was a by-election, with a lower turnout to be expected, what we can see in the graph isn’t an unusual pattern. In places where Labour did badly in 2017 and 2019, turnout tended to be lower than the national average, and often had been for some period of time. Where Labour picked up seats – as it did in 2017, turnout, by contrast, was up.

This correlation makes it clear that driving up voter turnout is an essential part of how the Labour party can claw back its support, and rebuild the left. But without a candidate who is able to mobilise local support, and a party that inspires people to vote for it, this isn’t going to happen. Polling immediately after the by-election found that the main reason people decided not to vote for the Labour party was the leadership (14%), followed by “unclear on policies” (11%).

Taking back power.

Unless Labour can come up with a clear, simple message that articulates what it stands for and what it will do, the party is going to suffer. In the parts of the country where Labour candidates actually managed to present a clear message, resounding victories followed. Labour councils like Preston, along with Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham, positioned themselves in opposition to the government and proposed positive alternative programmes, winning handily as a result. Burnham came into his own last summer, during a showdown with the government over coronavirus support for the city, but his programme for Greater Manchester included a solid commitment to bringing the city’s public transport back in-house.

in manchester, andy burnham took a strong, principled stand against tories and ran on a platform of ideas to improve people’s lives. if all the rumours are true it’s about to be a landslide there. labour can win, it just has to give people something to come out and vote for.

— Ben Smoke (@bencsmoke) May 7, 2021

It wouldn’t take much for Labour to offer a British version of Joe Biden’s programme in the US, with a platform of well-targeted spending promises – $100bn for broadband, $400bn for care work – and more union rights. Free broadband was a particularly popular policy in Hartlepool, with 69% of voters backing it. In this way, Labour has to understand the kinds of policies that appeal to voters – and offer big, clear, simple policies (like free broadband) that not only have mass appeal, but speak to the kind of country the party wants to build. Cheap and reliable broadband could be the backbone for the high-tech reconstruction of the northern economy, much like subsidised broadband investment in Cornwall has turned it into one of the fastest-growing tech sectors in the country.

Rethinking the Red Wall.

As The Economist pointed out in an excellent survey of the Tories’ new “Red Wall” suburbs, the Conservative party’s victories (and indeed the original “Red Wall” thesis) have been misunderstood. Typically, the explanation given for Labour’s losses is that the party’s traditional, working-class voters have been switching allegiance to the Tories. However, as James Kanagassoriam suggested in his original 2019 analysis of the “Red Wall”, these long-standing Labour seats contain a large number of people who match the profile of Tory voters across the country – those who are somewhat older, somewhat better off and who typically own their own homes. If these voters, Kanagassoriam posited, could be persuaded to switch sides, then the Tories could win big, building on a significant existing level of support across the north and the midlands. This, of course, is exactly what we saw happen last week.

Interesting question is why certain areas/conurbations vote differently to how you would expect them to demographically. How do we explain the rural, affluent seat that never votes Tory (Sefton Central), or that densely populated, London seat that does (Putney) (4/16)

— James Kanagasooriam (@JamesKanag) August 14, 2019

This might seem like a cause for despair, but the analysis can work to the left’s advantage.

For a fair bit of the country, the last decade has not looked too bad at all: wages and salaries may not have moved much in real terms, but house prices have risen sharply everywhere. The Tories’ selective austerity meant much of the population was protected from the worst of it – while of course a smaller group were viciously targeted. The horrible truth is that austerity hit poorer and Labour-voting places much harder than it hit richer and Tory-voting places, only becoming an electoral problem for the Tories once the cuts went so far they started hurting people who were either voting for them, or could be persuaded to vote for them – schools funding being the classic example. Under pressure, not least from an anti-austerity Labour party, the Conservative government has eased off and promised to end austerity. Johnson’s insistance that he opposed spending cuts, and rapid moves to increase some funding, helped contribute to the Conservatives’ thumping 2019 victory.

Although Brexit opened the door for the Tories to these northern former Labour voters, it was the promise of a stable economy, rising house prices, and protected public services that enticed them through, and the shift had been a long time coming. The scale of government support during the pandemic, insulating millions of people from much of the economic impact, underscored the Tories’ new-found commitment to public spending even as the economy took a hit. This is why Labour won’t win people back on vague cultural issues, or by becoming more socially conservative, as voices on its right are urging. Instead, Labour should cut through the culture wars flim-flam and focus on these voters’ hard economic interests.

Fundamentally, this is what Labour was set up to do: it is a party founded on the principle that those who work – including better-off workers and the middle class (workers “by brain”, as the old Clause IV put it) – needed a political party to defend their interests and improve their lot. It is in the party’s DNA to think and act like this, and so it will always be more convincing when Labour talks about those economic interests than if it tries to wrap itself in a Union Jack and say nothing.

Such interests can easily be taken in a broadly progressive direction: everyone benefits from better public services, and those with children especially have regular, direct experience of schools and education funding. Improvements to the environment, notably air quality and spending on public transport, can all point in the same direction too: that more public spending can mean a better quality of life. Rights at work, and perhaps even pay, which are absolutely crucial for some other parts of Labour’s coalition, may matter less than broader economic security (increasingly obtained through owning a house) and properly-funded public services.

Public services, however, are becoming a political problem for the Labour party. Historically, when things get difficult, Labour starts talking about the NHS. We saw this play out in the 2019 general election, which, towards the end, saw Labour’s campaign focus on the Tory threat to the NHS – just as Miliband did in 2015 and Brown did in 2010. Labour presenting a local(ish) doctor as the party’s candidate in Hartlepool was no doubt at least partly motivated by the same thinking.

Another tip for Labour: You should really examine how comfortable Boris seems to be with state spending. It is probably the most dangerous thing for your movement as he can outflank you by falling back on “but we are Tories” while also throwing money at popular policy

— Luke McGee (@lukemcgee) May 8, 2021

But after a strange year in which the Tories pushed healthcare spending to record levels, and the prime minister himself became a visibly and genuinely grateful recipient of NHS care, Labour’s safe space is looking less secure. Two in five healthcare workers reportedly say they voted Conservative in the local elections, up from rock-bottom support in 2019. In this way, the pandemic has presented a golden opportunity for the Tories to try to take ownership of the NHS.

What’s more, with Boris Johnson arriving in office in 2019, declaring he had always opposed austerity, and moving immediately to increase schools funding – a major Tory weakness in 2017, with voters switching to Labour citing it amongst the top three reasons they moved votes – the Tories are not necessarily going to be the party of austerity they once were. The danger Labour faces, particularly in its former heartlands, is the kind of Toryism Teesside mayor Ben Houchen offers: bringing the local airport into public ownership, talking up the thousands of skilled jobs the “green industrial revolution” will create and, crucially, backing it up with cash from the treasury’s pork barrel.

It is, of course, possible that the government might give in to temptation and start wielding the Osborne-era axe again – there are £4bn further spending cuts pencilled in. But Johnson is, if nothing else, good at winning elections and thinks constantly about how to win the next one. (This makes him the antithesis of Labour: the party is bad at winning elections and obsesses continually about how it could’ve won the last one.) Given that austerity is a widely unpopular policy – and particularly unpopular in some of the new seats the Tories won in 2019 – there is no way that Johnson will go into the next election with spending cuts if he can possibly avoid them – and, of course, he can avoid them.

Labour’s automatic claim of being the party of public services, therefore, looks to be on shakier ground – at least for those public services that tend to matter to people who might shift their votes at the next election, like schools and hospitals.

There are, of course, some glaring exceptions to this. First, that, as a result of the pandemic, very large numbers of people have now had direct contact with the miserly social security system; second, that the ongoing cost pressures of Covid-19, from healthcare to local authorities, will demand more money than the Conservatives may wish to supply; third, probably most important politically, that the Tories having loudly promised to fix the care system back in 2019, are now setting up an almighty row about it without an obvious resolution.

“Senior Treasury officials” are kicking up a stink about the government’s proposed funding solutions to a care system in worsening crisis, bewailing both the cost and what they claim are its unfair outcomes. Labour could be all over this, championing care workers’ pay and conditions and demanding a fair solution, as Angela Rayner proposed before the election. Common Wealth’s work on an “industrial strategy” for care is a good example of a comprehensive policy offer.

The end of a Britain-wide politics.

But a strategic focus on a key part of public spending would be only one part of the solution. The other elements are more challenging and will require those of us on the left to think a bit differently about how we can assemble the coalition needed to beat the Conservatives.

The difficult truth is that the British road to socialism, or even social democracy, is almost certainly over – meaning that the days of a Labour party that represented every part of Britain, aspiring to form a majority government in parliament, are gone, and will not come back. Its last hurrah was perhaps the 2017 election, and even then, as we all know, despite the biggest surge in its vote since 1945, the party fell short. If we want to disrupt the Tories’ emerging hegemony – and they clearly have every intention of dominating this century just as much as they dominated the last – we need to draw on a wider set of forces and a new political language.

Part of that is recognising that there is no longer a genuine Britain-wide politics: Scotland, and increasingly Wales, operate differently to Westminster. The pandemic has accelerated this trend, but also – dramatically – created new, regional voices and sources of political authority within England, of which Andy Burnham is the most obvious example. (Indeed, it’s no wonder that the Tories have already threatened to move against the democracy of elected mayors.) Labour should think of itself more as a Britain-wide coalition, including coalitions of regional support inside England, than a single Britain-wide party. That should include allowing, as Mark Drakeford in Wales has said, the right of Scotland and Wales to democratically remove themselves from the United Kingdom.

Relatedly, former Labour minister John Denham has pointed out that, whilst Labour leads amongst those who identify as British rather than English, the Tories have a clear lead amongst those who call themselves English first. Hartlepool, it should be noted, has one of the highest rates of ‘English more than British’ identifiers in the country. Just as the party needs to be more open to distinct Welsh or Scottish politics, it needs to construct a progressive English politics, most likely by drawing on the clear regional identities of different parts of the country and promoting further devolution of powers. At the very least, waving the all-Britain flag of the Union Jack isn’t going to cut it anymore – if the flags-and-beer approach ever does.

Similarly, in the places where Labour did make breakthroughs last week – the West of England, Cambridge and Peterborough mayoral races, for example, or in the swing of councils like Falmouth into Labour hands – the party must act strategically to take advantage of this crumbling “Blue Wall”. There are rumblings of concern amongst the Tories, but as many commentators have pointed out, whilst the cities are pricing out young, often graduate workers, into smaller towns and suburbs, and thus gradually pulling these places leftward, this process is too slow and too limited to compensate for the extent of losses in the north, and especially, in the midlands.

And while Covid-19 is accelerating this process of city exit as working from home spreads, demography alone will not produce the political shift that is needed. With anti-Tory forces scattered and divided across the south, the need for functioning, on-the-ground alliances with other parties is becoming more and more apparent: perhaps most obviously where the Greens and Labour directly contest for votes.

A sharp change in direction.

That said, the construction of the new Tory hegemony depends on more than just electoral politics. It means the restructuring of the system itself – from the introduction of voter ID for voting to the massive extension of powers in the Police Bill. Protests and campaigns against this emerging “authoritarian capitalism” are crucial, and the left should prioritise pulling both together. But Labour itself needs to work against its own worst instincts here: on the grounds of elementary democratic principle, and from the needs of its own political survival, this authoritarian restructuring should be consistently opposed. Opposition to vaccine passports was a welcome part of this defence, as was growing resistance by Labour MPs to nodding an extension of the Coronavirus Act powers through parliament.

None of this will be easy. If the Labour party continues down this path, it is not implausible that, in the near future, it could fade into irrelevancy. A sharp change in direction is needed: clear policies focused on material interests, moving power out of Westminster and building new coalitions of support are the steps Labour now needs to take if it is ever to form a government again.

James Meadway is an economist and Novara Media columnist.