Has Keir Starmer Heard of Pasokification?

It appears the Labour leader needs a history lesson.

by Joana Ramiro

20 May 2021

You need only compare the annus horribilis of 2016 (RIP Harambe) to the neverending nightmare that has been 2020-21 to know that we live in a world where change is fast and constant. It is therefore beyond me why the current Labour leadership insists on living in 1997.

The local elections earlier this month spelled disaster for progressive politics wherever Southside intervened, parachuting in candidates and campaigners reminiscent of a time when Chocolate Salty Balls was a national obsession (1998, for those too young to remember). Conversely, the party yielded good results wherever the Labour candidate demonstrated their own voice and a finger on the local pulse. No wonder, then, that the term “Pasokification” has returned to the political lexicon.

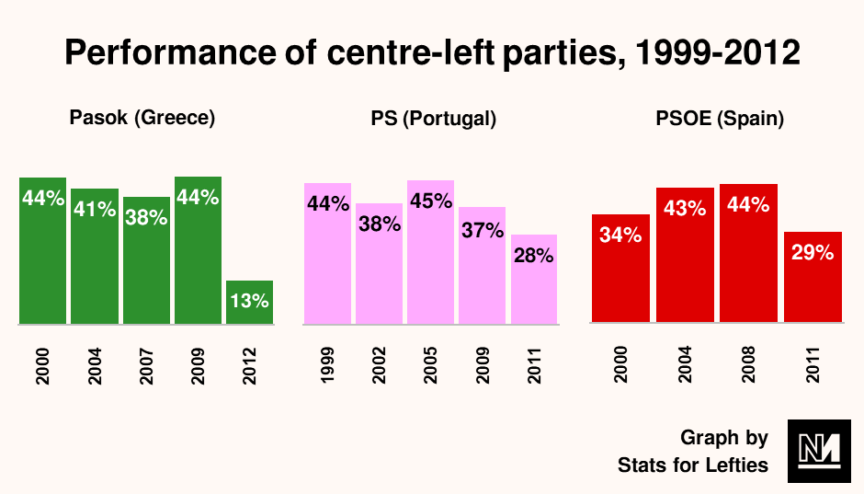

Pasokification took off in the early 2010s, when Labour’s Greek counterpart – the Panhellenic Socialist Movement, or Pasok – came crashing down in the polls. Pasok had overseen the implementation of severe austerity measures in Greece following the 2010 national debt crisis. Its policies were met with such anger by the Greek population that the then prime minister George Papandreou – son of Pasok founder Andreas Papandreou – was forced to resign in 2012. When George took office in 2009, Pasok had won with 43.9% of the vote. In the snap election of January 2015, it failed to gather 5%. Pasok went from 160 seats to 13 in the space of six years. Today, the party exists only in the fold of the centre-left coalition Movement for Change, also known as Kinal, the third-largest political force in Greece behind the governing conservative New Democracy party and the far-left, though now much-mellowed, Syriza.

Pasok’s fate prompted pundits to look at the trajectory of social democratic parties across Europe. From Portugal to Poland, social democrats were losing ground. In some places, such as Greece and Spain, their votes were being taken by new left-populist forces with charismatic leaders and large grassroots mobilisations. But in places like Italy, Hungary and Sweden, the threat came from the far right, whose socially conservative policies and rallying cries against corruption seemed to echo with sometime Labour voters.

First, a bit of history.

The history of social democratic parties across Europe has been far from uniform. Some came into being at the turn of the 20th century, as the effort of industrial workers striving for a political voice. Others were born with their countries’ democratic revolutions in the 1970s or the fall of the Iron Curtain in the early 1990s.

Their rhetoric and iconography vary in accordance with their individual national histories and cultural appreciations. Some general secretaries will use “comrades” to crowds; to others, the word is anathema. Their manifestos contain varying degrees of reformism. Many have undergone numerous transformations and have been the very grounds for brutal battles of ideas.

Like many of its northern European counterparts, the UK Labour party was once an active member of the Socialist International but has since 2013 been more closely associated with the Progressive Alliance. The transition from an international political network expressly named “socialist” to one branded as “progressive” tells you all you need to know about the ideological changes that have taken place in those parties in the last decades.

What they all had in common until the financial crisis of 2008 was being the most electorally successful form of working-class political organisation. In other words, they all had a track record of being either in government or the main opposition. Pasokification meant there were now more broncos in the race. Social democracy’s winning streak was over.

A decade later, the political environment has continued to diversify, with new electoral constellations sprouting left, right and centre. Many of the dissatisfactions that pushed constituencies away from Labour and its sister parties continue unsolved, often exacerbated by new problems, of which the most blatant is coronavirus. Yet not all European social democratic organisations have ended up like Pasok. The Portuguese Socialist party (PS) has been in power for the last six years. The Spanish Socialist Workers’ party (PSOE) has ruled with the support of the far left since 2018.

Iberian socialism.

No countries had more to learn from the demise of Pasok than Portugal and Spain. Both Ibearian countries suffered from a similar problematic mix of growing surplus deficit and public sector debt with minimal GDP growth as Greece. Alongside Italy and Ireland, their initials spell out PIIGS, an acronym used by economists as shorthand for the countries worst affected by the European sovereign debt crisis.

Until the 2008 financial crisis, Portugal had a neoliberal PS government led by José Sócrates, a man who went from a Tony Blair tribute act to being indicted for money laundering and corruption. Like in Greece, the national debt crisis that followed was met with the imposition of severe austerity measures by the so-called European troika (made up of the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission and the European Central Bank) and willingly accepted by the Sócrates administration. With a government incapable of having a hold on the spiralling economic crisis and popularity rates slashed, Sócrates stood down in 2011. The snap elections that followed put the conservative Social Democratic party (PSD) in power for four years. When first elected in 2005, José Sócrates led a parliamentary group of 121 MPs. Only 74 returned in 2011.

Similarly in Spain, PSOE governed between 2004 and 2011, under the leadership of its own Blair impersonator: José Luis Zapatero. Like in Portugal and Greece, Spain responded to the financial crisis with a set of austerity measures, while requesting several rescue packages from the eurozone. Spain’s already large unemployment figures grew exponentially. The anti-austerity movement, known as the Indignados, or “Outraged”, brought hundreds of thousands to the streets in the summer of 2011, pushing Zapatero to resign in July. By November, as Spaniards took to the polls on yet another crisis-driven snap election, unemployment was at 23%, the highest in Europe. In Madrid, as in Lisbon, conservatives took power for the following six years. Voters wanting nothing to do with social democrats who couldn’t handle a crisis, imposed reactionary economic policies and didn’t even attempt to resist Brussels’s diktats.

In both Iberian countries, as conservatives took their turn on tightening purse strings and pushing even more people into total destitution, the PS and PSOE fought over which direction to take in order to avoid an end similar to that of Pasok. In 2014, pushed in part by the emergence of new or renewed far-left forces, Portuguese and Spanish social democrats picked new secretary generals, both of which were clear departures from their previous leaders.

The current Spanish PM, Pedro Sánchez, stood on a platform that vehemently rejected the technocratic approach and the possibility of a grand coalition while supporting policies of state investment, progressive taxation and constitutional reform to tackle growing regional pressure from Catalonia. While never a radical (he beat the socialist candidate José Antonio Pérez Tapias in the leadership race), Sánchez was able to appeal to both the left and soft-left wings of his party. He made sure that his meetings with trade unionists were well publicised, and while originally opposed to a pact with the far-left Podemos party, Sanchéz finally gave in by November 2019, forming the coalition that has governed ever since. The unravelling of the Podemos leadership in the past weeks could offer PSOE an opportunity to take some of the far left‘s constituency and build a majority social-democratic government. Time will tell.

Sanchéz’s Portuguese opposite, António Costa, won the first open primaries run by PS in 2014 with 68% of the vote. His opponent, the incumbent António José Seguro, was perhaps more serious when it came to distance himself from the legacy of the party’s last premier José Sócrates. But he had proven to be a weak opponent to the conservative government, and too square to imagine economic proposals that steered away from further spending cuts. Costa, on the other hand, was well known to the Portuguese public, having been a popular Lisbon mayor and television pundit in the preceding years. By the time general elections came around in 2015, Costa was cautious but unafraid of developing a confidence and supply agreement with the far-left Left Bloc/Bloco de Esquerda (BE) and Communist party in order to take power. So successful was his “contraption” government that when seeking reelection at the end of 2019, PS was able to ditch its far-left partners and take office with 36% of the vote. According to data collected by Portuguese state broadcaster RTP, PS is currently polling at 38%. Portugal’s third political force, the BE, holds its ground with a slight drop. The Communists have fallen by one percentage point, ceding fourth place to the far-right party Chega.

Lessons learned.

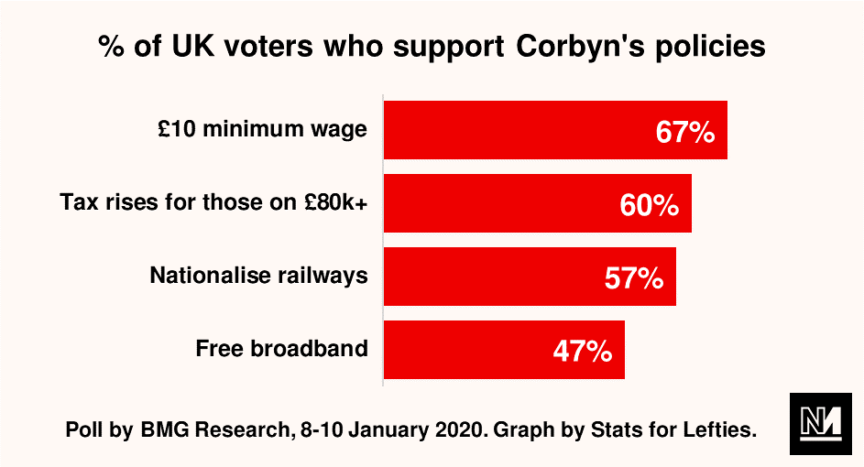

None of these successful social democratic parties is as radical or inspiring as Corbyn’s Labour. Nor have any of them matched Corbyn’s 2017 40% share of the popular vote. It would be fair to suggest at this point that, by any measure other than first past the post (FPTP), Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party did extremely well for a social-democratic organisation in Europe. This being the case, and since the discontents of the populations across the global north mostly stem from similar issues: welfare systems struggling under lack of investment, rapidly ageing populations, and the growing disparity between metropolitan areas and the rest of the country, to name but a few. One could argue that the problem was not the political direction the party took under Corbyn’s leadership. Quite the opposite.

But until electoral reform becomes a mainstream demand, we are stuck with FPTP. And if Labour (and the left as a whole) is to be successful within this system – if it is serious about dethroning the Tories and forming a progressive government – it must not only look at Pasok as a cautionary tale, but learn the lessons of those parties that survived the cull and thrived in an age of populism and emergency.

Considering the recent histories of PS and PSOE, it is disheartening to hear Labour leader Keir Starmer’s volte-face over the weekend. Speaking at the Progressive Britain conference on Sunday, Starmer rejected the 2017 manifesto he so proudly defended while seeking election as leader. Alongside him stood no other than Peter “Prince of Darkness” Mandelson, the architect of Blairism and devotee of the type of social democracy that voters shunned throughout the 2010s.

European social democrats realised a more leftwing rhetoric and policies were necessary to win (while, of course, shying away from anything truly radical). And while they didn’t follow the exact same script, Costa and Sanchéz know that the years of neoliberal politics are over. Across Europe, progressive parties are ditching the yuppie mentality which characterised New Labour, and to which Labour centrists continue to cleave. Faced with very different material conditions – from sluggish economic growth to environmental precarity – they are offering new, collective solutions, often pinched from far-left manifestos. Unlike British Labour, social democrats across the continent have learned that maintaining links with the far left equals electoral success.

Why Starmer has so far been unable to learn this lesson – be it out of incompetence or pride – is yet to be determined. But unless he learns quickly, his party will follow Pasok’s fateful collapse into irrelevance.

Joana Ramiro is a journalist, writer, broadcaster and political commentator.