A Brief History of the Taser, the ‘Less-Lethal’ Police Weapon That Keeps Killing People

The police’s most controversial weapon is even worse than you thought.

by Sandeep Sandhu

26 May 2021

The 2016 killing of Dalian Atkinson at the hands of West Mercia police has, at last, made it through the slow churn of the UK’s underfunded justice system. Nearly half a decade after Atkinson’s death, the policeman who tased the former Premiership footballer – for six times longer than standard practice – is finally standing trial. While racism clearly played a huge part in this tragedy and its unfolding, Atkinson’s case also raises specific questions about the role of Tasers in British policing.

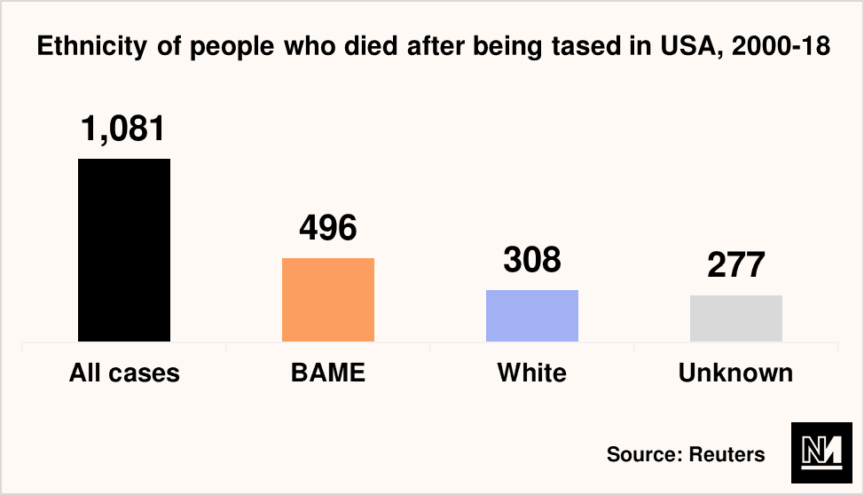

Despite being touted as a “less-lethal” solution to public order issues than firearms by numerous policing organisations, a Reuters investigation in the US documented over 1,000 cases between 2000 and 2018 where people died after being tased; electroshock was formally cited as a cause of or factor in death in over 150 of these cases. And that’s just the deaths: organisations from the American Psychological Association to Arizona State University have confirmed the cognitive damage Tasers can have, especially in the short term, raising questions about the morality of reading somebody their rights after they’ve been tased. Then there are the head injuries caused by falls after being tased. Surprisingly, electrocuting someone is not without its risks.

If Dalian Atkinson was an American pro footballer and had died after being brutally tasered by US police, who were then charged with his murder, the British press would be all over it. Have you noticed the press silence? #dalianatkinson #blacklivesmatter https://t.co/GyMwJ76Do0

— Black and Asian Lawyers For Justice (@BameFor) May 18, 2021

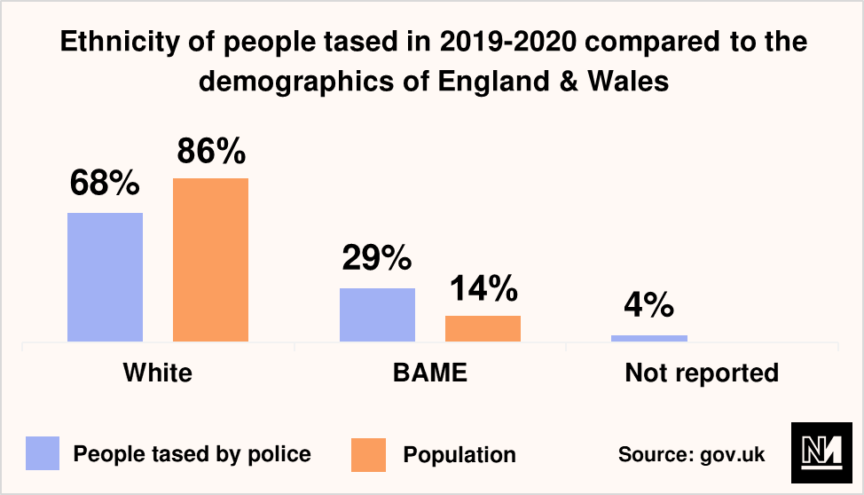

Although Atkinson’s case has recaptured public attention, he is by no means the first person in the UK whose death was related to the use of stun guns. A 2019 Amnesty International report, for example, noted that there have been 18 deaths linked to Tasers since they were first introduced to UK police in 2003. Beyond the physical effects of the Taser itself, an experiment with the City of London Police found that officers carrying Tasers led to greater hostility in officer-public interactions. As usual, people of colour suffer disproportionately when it comes to such incidents: Black people are three times more likely than their white counterparts to be the victim of tasering.

Two forensic pathologists quoted in the inquest for the death of Marc Cole, a 30-year-old white man who died at the hands of police in 2017, stated that the Taser “played a more than minimal” role in his death. They argued for a government review of police Taser use and training, focusing on Tasers’ use on the most vulnerable, such as those experiencing poor mental health and intoxication.

A spokesperson for the College of Policing responded by saying that if “Sacmill [Scientific Advisory Committee on the Medical Implications of Less-Lethal Weapons], Axon and the College had been called to give evidence … information could have been provided that would have been highly likely to be useful.” They added: “In performing its role SACMILL has taken account of a body of evidence relating to the use of Taser. The College is not able to comment on the detail of the evidence that has been reviewed.” It remains unclear what “useful” information would have been offered up, but the implication is that the college would have found a way to absolve itself – and Taser use – of any guilt.

In 2014, Staffordshire Police shot Adrian McDonald (34) with a Taser during a period of distress. His heart stopped beating and he died in the back of a police van. No ambulance was called. pic.twitter.com/E2Pb5fZFl3

— NPMP (@npolicemonitor) August 2, 2020

Axon, formerly known as Taser, is – thanks in large part to their litigiousness – effectively the sole manufacturer of the electroshock weapon in the world. The company has a long history of downplaying the lethality of the Taser – a history that is rooted in greed, litigiousness and racism, and one that utilises levers of power and influence that we often see when wealth, commerce and law enforcement intersect, usually to the detriment of traditionally marginalised communities. It’s a story as old as America itself, and as always, one that the UK is in danger of importing.

There are a variety of figures in the Axon orbit who play an important role in obfuscating the link between Tasers and deaths in police custody. John Peters, president of the Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths, is one of them. His institute is one of the largest providers of Taser training in the world and pushes the concept of “excited delirium” (ExDS). This condition, not recognised by World Health Organisation or the American Medical Association, and not listed in the most recent International Classification of Diseases or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, is characterised by aggressive behaviour and extreme physical strength, and usually linked to the recent use of a stimulant, often cocaine. It is diagnosed post-mortem and most often in young, adult males, who are usually Black, and more often than not in restraints after being tased while in police custody.

The condition has been described by researchers at The Brookings Institution as a “misappropriation of medical terminology, used…to legitimi[s]e police brutality”. Although primarily an American phenomenon, “excitement” was listed as one of the causes of death in the coroner’s report on Cole, and ExDS is mentioned in the UK College of Policing materials.

The history of ExDS is rooted in racism. The condition was first identified in 1985 by medical examiner Charles Wetli to explain the sudden deaths of seven recreational cocaine users, five of which occurred in police custody, as well as the deaths of 32 Black women sex workers in Miami during the 80s (they were later found to have been strangled by serial killer Charles Henry Williams).

Since then, ExDS has been used by US officers to explain away deaths in police custody, primarily those of young Black men. Symptoms include “failure to respond to police” and “continued struggle despite restraint”. The idea that ExDS gives victims “super strength” and makes them “impervious to pain” is also a popular one in law enforcement circles, giving overzealous officers an excuse to excessively tase. As a majority of ExDS deaths occur after stun gun use, Axon has a vested interest in legitimising the condition, despite the medical community’s near-unanimous agreement on its dubiousness.

Axon uses a variety of tactics to muddy the waters when it comes to the lethality of Tasers, but one of its most successful is the use of paid medical practitioners to produce studies and argue on its behalf in court. This tactic is best personified by Dr Jeffery Ho, whose ethical standards have been called into question after a project on which he was lead researcher sedated emotionally disturbed people with ketamine without their consent.

Ho has been trotted out by Axon and other organisations, such as Police Magazine, that have a vested interest in the continued use of Tasers with minimal oversight. He argues that stun guns aren’t deadly, going so far as to write in a 2005 study: “It has never been scientifically proven that a Taser has directly caused an in-custody death.” The study was paid for by Axon.

But Ho’s links to the company go much deeper than being paid to write about the non-lethality of Tasers. As of 2019, Ho was Axon’s contract medical director, a job he performed at the hospital he worked at, the Hennepin County Medical Centre (HCMC). Axon funded HCMC to the tune of around $140,000 a year so Ho could complete his work for them on-site, a vital lifeline for a hospital whose parent company showed losses in the tens of millions in 2019. The link between HCMC and Axon was not displayed on the hospitals’ website at the time and was only discovered when the local paper, Star Tribune, ran an expose.

Ho has also been used as a star witness by Axon in numerous court cases across the US and Canada, billing the Taser maker up to $400 an hour for legal services. The Axon life hasn’t just meant stuffy courtrooms for the Minnesota-based doctor, though. Ho has been sent all over the world to give presentations about Taser technology. When you also take his connections with local law enforcement into account – he’s a qualified police officer – you get an extremely murky ethical picture.

Tasers are mostly deployed with no fatalities, something Axon and law enforcement departments all over the world continue to shout about, while staunchly ignoring the weapon’s other health impacts, including its particularly deadly effect on vulnerable people and those with pre-existing heart conditions. Even so, the UK-based Defence Scientific Advisory Sub-committee on the Medical Implications of Less-lethal Weapons has okayed the use of the devices, and in police advice, there are several caveats around excessive use to avoid situations like what happened with Cole and Atkinson. In recent years there have also been papers written by Dr Deborah Mash, which trace the roots of ExDS through medical history to give the condition more legitimacy, thus lending credence to the idea that Tasers are needed to subdue seriously strong and delirious criminals.

Axon, the company that manufactures Tasers, has been on a Philip Morris-level disinformation sales campaign to get every city, including SF, to buy a buttload of Tasers. still remember the absolutely ridiculous presentation they gave to the SF Police Commission in 2018

— larry “white boy” summers🌹 (@uhshanti) April 12, 2021

That said, Axon’s behaviour is not that of an innocent company realising there’s an issue with its product and then scrambling to do better: between the production of dodgy medical papers, litigious actions against medical examiners who implicated Tasers in deaths in police custody, and the sharing of “published research materials [about ExDS] when it may benefit a particular agency that is investigating a specific incident”, there is plenty of obfuscation going on from the company. Even researchers like Mash, who is associated with the University of Miami, can’t really be trusted since she was paid by Axon to testify on its behalf in lawsuits against the company.

It’s clear that Taser use is far more harmful than implied by Axon and various policing bodies. If Atkinson’s death is to reopen the conversation around the use of less-lethal weapons in this country, we must ensure that Axon doesn’t manage to achieve what it has in America, embedding itself into investigations around the deadliness of Tasers to shape the narrative and proactively seeking out medical examiners to convince them to put ExDS as a cause of death. Its overuse of lawyers, payment for biased research and incestuous relationship with law enforcement needs to be controlled, otherwise, we’ll be sure to see more preventable stun gun deaths here in the UK, while Axon’s profits pile up alongside the bodies.

Sandeep Sandhu is a writer based in Edinburgh.