It’s the Housing Market, Stupid: How Property Became the Battle Line of British Politics

Our political landscape has been warped by a single asset.

by Samuel Earle

31 May 2021

According to a prominent, post-Brexit narrative, what drives British politics is no longer economics but culture and values. The Labour party, in this telling, has lost touch with the people it purports to represent. The Great British Public are uninterested in Corbynesque plans for radical economic transformation – what they want is a party that is proud of its country, ready to wave the national flag and, culturally-speaking, cares less about ‘fringe’ issues like racism, sexism, and transphobia and more about ‘real’ issues that affect people’s lives.

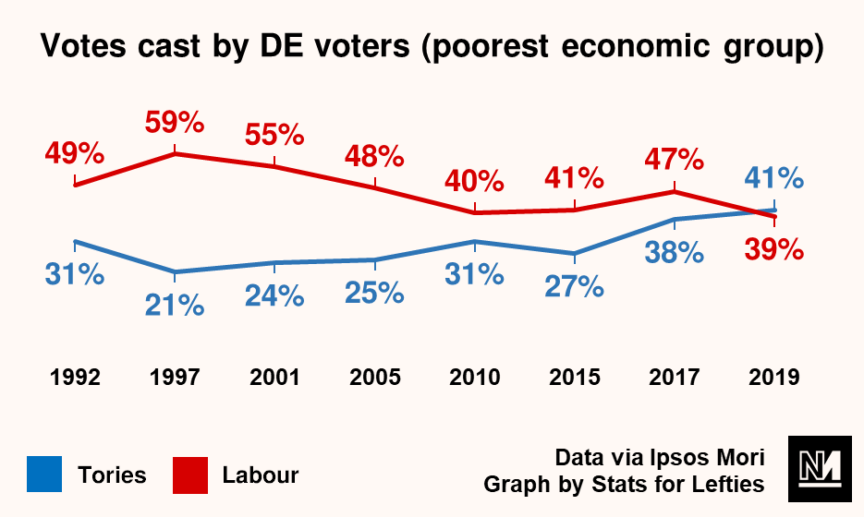

Many of the headlines generated by Boris Johnson’s 2019 election victory added grist to this mill: it was the Conservatives’ largest majority since 1987, and Labour’s lowest tally of seats since 1935. In 2019, the Conservatives’ share of the vote amongst poorer Britons rose to its highest on record. Many seats in the much-mythologised ‘red wall’ – struggling post-industrial constituencies in north and middle England traditionally considered Labour strongholds – swung the Conservatives’ way. Meanwhile, the only new seat that Labour gained spoke volumes: the wealthy West London borough of Putney.

When affluent London constituencies are backing Labour and working-class ones in the north are turning Tory, it might be fair to assume that the famous refrain of 90s politics – “it’s the economy, stupid” – is redundant. But lying beneath excited tales of culture wars and Johnson’s populist genius, the contours of a more familiar reality can be discerned: one where Britain’s political landscape has not transcended economic interests, but rather has been transformed by them – where the recent political shifts have little to do with either Jeremy Corbyn’s failings or Johnson’s cunning, but reflect trends that have been evolving for over 50 years.

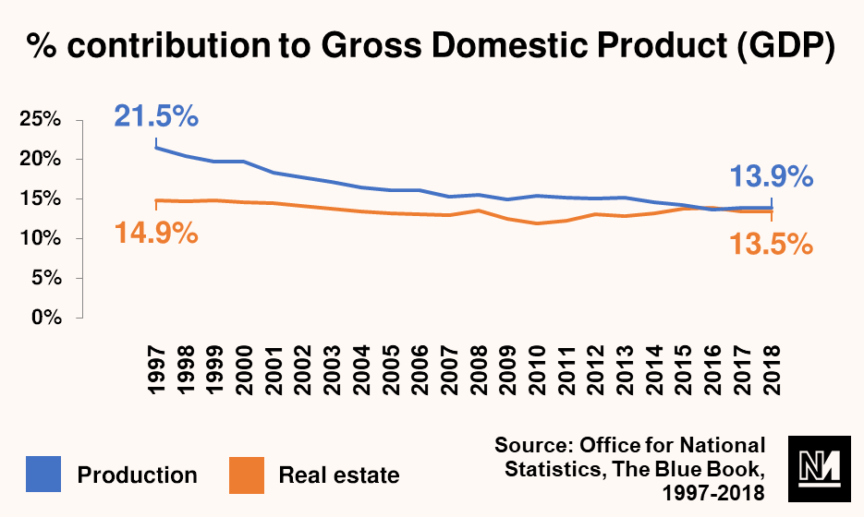

Perhaps one statistic more than any other crystalises Britain’s economic transformation. Since 1971, the stock value of real estate has risen from $60bn to over $6tn. In recent years, this has led to real estate contributing almost as much to GDP (percentage-wise) as all production industries. And just as having a job in the manufacturing industry once determined how one voted, its eclipse by the housing market has had a similar effect: the economic fact of whether or not one owns a home has long been at the heart of our political identities, but as the nature of owning (and not owning) a home has changed, so too has our politics.

It is hardly a novel state of affairs that homeowners are wary of radical change, and so traditionally vote Conservative. As the social reformer Francis Place declared in 1831, with the whiff of a workers’ revolution in the air: “Every man who has property to lose is bound to do all he can to avert it.” The same premise guided Margaret Thatcher’s ‘right to buy’ policy 150 years later, where council houses were sold to tenants at bargain prices, with the hope of creating a new class of homeowning Tory voters. This also explains why, amid a national housing shortage, the Tories have no interest in building more council housing, and why Johnson received £11m in donations from property developers in his first year in charge.

But while a majority of homeowners continue to vote Tory, today’s economic context is in other ways unprecedented. While house prices have soared, wages have ground to a halt: house prices have risen nearly three times faster than wages since the 2008 recession, amid the longest period of wage stagnation since the Napoleonic wars. Meanwhile the manufacturing industry has all but disappeared, and its old identities and party loyalties along with it; in its place the service industry is now ascendant, accounting for four in five jobs. The work pays less, is less unionised, and is concentrated in larger cities. In this context, housing is one of the few economic securities Britain offers – the Bank of England advises that a property is now “a better bet” for retirement than a pension. But it comes with a catch: in the areas where you’re most likely to find a job, you’re also less likely to be able to afford a house.

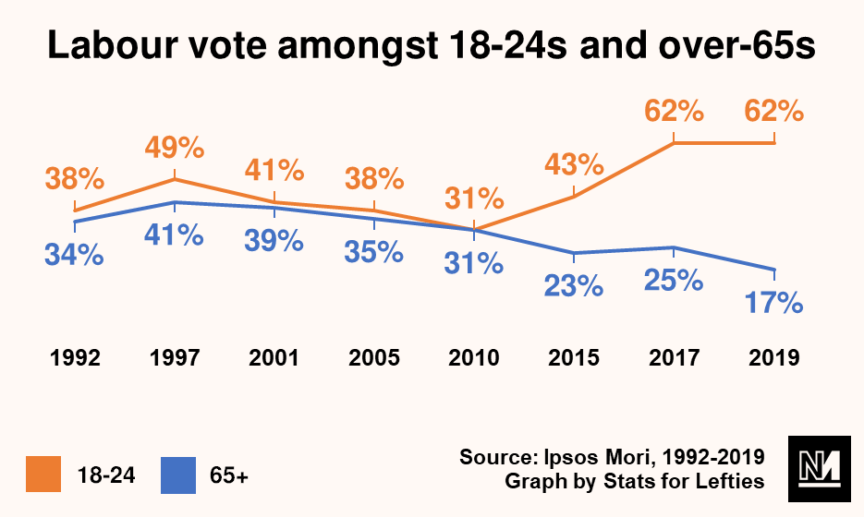

One of the effects of this imbalanced economy is a vicious cycle where a growing number of young people – usually Labour voters – leave rural areas for work or study, typically for places where Labour already enjoys comfortable majorities. They leave behind aging populations in their local communities and higher-than-average rates of homeownership. According to a 2020 study, Britain is now one of the most age-segregated countries in the world; in the past 25 years, rural areas have aged twice as rapidly as urban ones. This age segregation is playing out politically: in the 2019 general election, the age divide was greater than ever, according to Ipsos Mori.

There is a cruel irony in all of this. “Tory economic policies which have laid waste to industrial towns have ended up increasing their propensity to vote Tory,” as the journalist Jonn Elledge recently noted. But this follows a pattern that the Tories know well. Whether in pursuing Brexit or austerity, it seems that the more hostile Britain is for living in, the more accommodating it is for Conservatives winning in. And where blame for the state of Britain must be apportioned, the Tory press is always on hand to point the finger at Labour, even as it seems trapped in permanent opposition. (Soon, one imagines, the Tories might have to at least let Labour win, simply to refresh the banks of ‘it’s-Labour’s-fault’ discourse.)

Yet whichever way it is spun, the economic story underlying Tory success is an unhappy one. The attractiveness of reframing it in terms of cultural shifts is plain: it lets the Tories drum up their populist credentials and pushes scrutiny of Britain’s hollowed-out economy – and the Tories’ culpability – to one side, while heaping blame on Labour for losing touch with its base. Under Keir Starmer, Labour seems determined to not only internalise this Tory narrative, but amplify it – even as polls show that views in the ‘red wall’ are largely consistent with the rest of the country.

This doesn’t mean that the vicissitudes of the housing market can explain everything in British politics. Brexit reconfigured the electoral map and, especially in the north and middle England, served as a gateway drug for many voters to turn Tory (although there is evidence, according to an important study by David Adler and Ben Ansell in 2019, that the housing market was influential in the referendum result as well.) But seeing the Tories’ ascendancy through the lens of homeownership, in a stuttering economy, at least sheds a light on why a millionaire property developer in London and a retired homeowner in Hartlepool can find common cause with the Conservatives. The answer isn’t a shared set of cultural values.

Samuel Earle is a writer based in London. His work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, the London Review Books and elsewhere.