Biden’s New Cold War With China Will Be Justified With Racism

‘We’ versus ‘they’ narratives have shaped global politics for centuries.

by David Wearing

28 June 2021

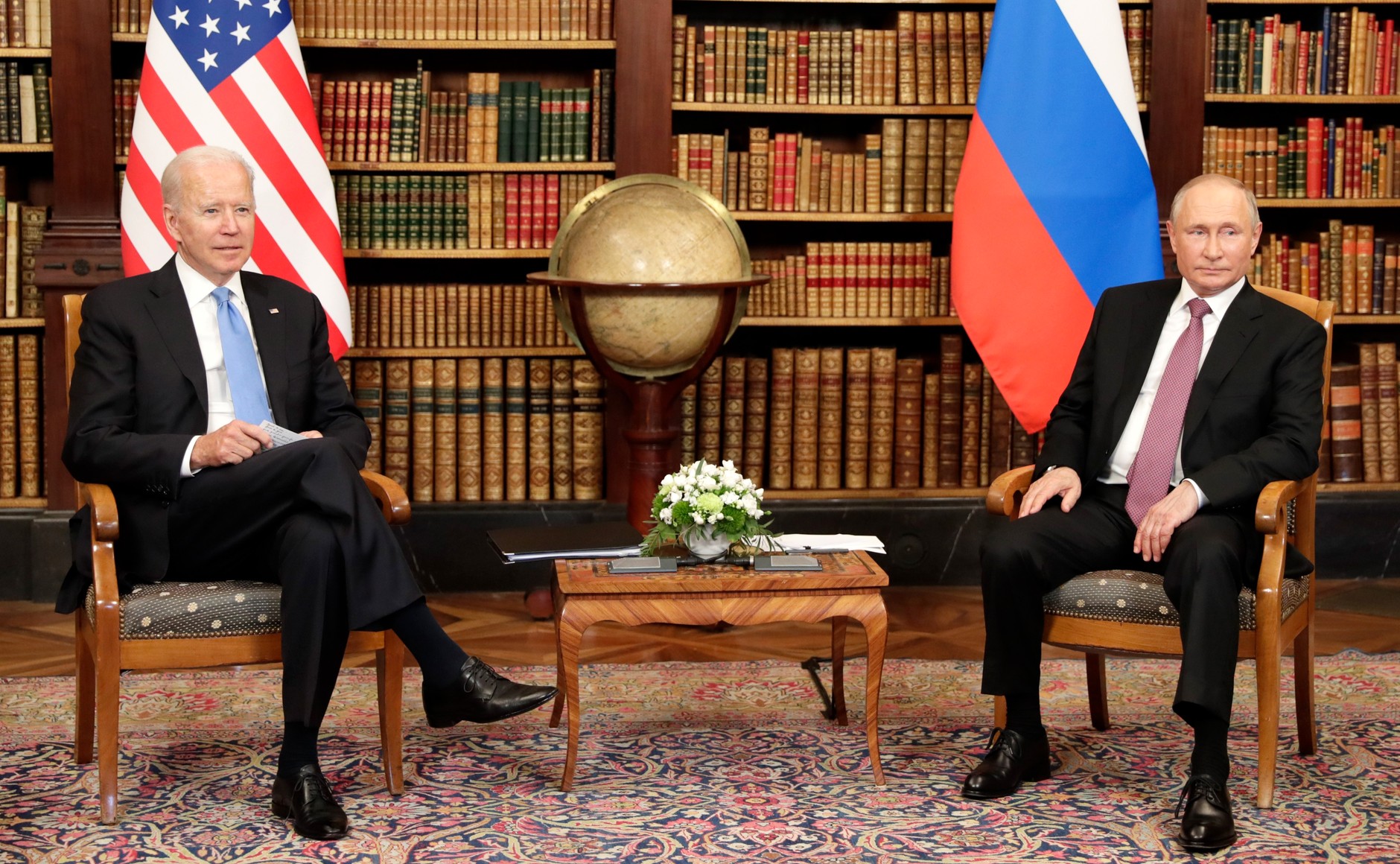

Confrontation with China is shaping up to be a central theme of Joe Biden’s presidency. At recent meetings of the G7 and NATO, Biden’s main aim was to corral and recruit allies for Washington’s new Cold War. A subsequent summit with Vladimir Putin appears to be the first step in a long-term effort to shape a US-Russia rapprochement, and thus prise Moscow and Beijing apart. Biden even frames his ambitious programme of domestic investment as necessary to get the US economy match fit for competition with China. This range of moves could set the scene of international politics for decades to come.

In a recent article for Foreign Affairs, Bernie Sanders offers some perceptive observations about the dangers of a US-China Cold War. The more obvious point he makes is that the major challenges facing the world today – from climate change to global pandemics – require forms of international cooperation that will be undermined by Sino-American antagonism. But he also highlights another dimension of the problem. Sanders warns that “the growing bipartisan push for a confrontation with China […] risks empowering authoritarian, ultranationalistic forces in both countries”. He reminds us that the so-called ‘war on terror’ of the 2000s “gave rise to xenophobia and bigotry in US politics”, serving as a lesson that “Americans must resist the temptation to try to forge national unity through hostility and fear”.

“Right now, the United States is more divided than it has been in recent history. But the experience of the last two decades should have shown us that Americans must resist the temptation to try to forge national unity through hostility and fear.” https://t.co/leJKuguOYK

— Kate Aronoff (@KateAronoff) June 17, 2021

The dynamics Sanders touches on here are worth exploring in more depth. To understand international politics, it is necessary but insufficient to analyse state-to-state relations and capitalist economic structures. We also need to think about the political discourses which legitimate state policy and which shape dominant understandings of the international. A key organising principle in such discourses is a chauvinistic sense of who ‘we’ are, juxtaposed with a derogatory sense of who ‘they’ are. This has been a recurring ideological theme from the colonial era to the present day.

Take the precedent that Sanders identifies: the ‘war on terror’ and Islamophobia. Dominant political discourse in the West after 9/11 repeatedly posited a backward Muslim majority world as a security threat, and the forceful spread of ‘western values’ as the solution to the problem. ‘Our’ essence was the liberal Enlightenment, while ‘theirs’ was violent fanaticism. This was set up as the defining feature of the conflict, and the master framing of our righteous war.

These themes were expressed most vividly by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, when he justified the invasion of Iraq in the following terms:

“We needed to go over there, basically, and take out a very big stick right in the heart of that world [and go] house to house from Basra to Baghdad […] basically saying ‘Which part of this sentence don’t you understand? You don’t think we care about our open society? […] Well, suck on this!’”.

There is a straight line between the systematic torture and sexual humiliation of Iraqi prisoners by US troops that was exposed during the occupation, and the dehumanising, racist language that was a constant feature of western foreign policy discourse during the 2000s. That line extends into the 2010s, where the Islamophobia stoked by the ‘war on terror’ blew back with gale force into western domestic politics.

The mainstreaming of Islamophobia by liberals and the centre-right fed directly into the far-right’s resurgence on both sides of the Atlantic. The central problem of the ‘migrant crisis’ of the mid-2010s was not the people who had made the entirely reasonable choice to flee war, tyranny and poverty. It was the racism of the countries they were attempting to flee to. That racism was successfully mobilised by Brexit campaigners in the UK, a tactic whose by-product was the fascist murder of the pro-migrant MP Jo Cox. At the same time in the US, Islamophobic rhetoric was at the heart of Donald Trump’s victorious presidential campaign. In every case, a chauvinistic image of a national or civilisational ‘us’ was set up against a dehumanised image of a generalised, threatening ‘them’.

Darren Osborne and Thomas Mair were far right terrorists. They were emboldened by the hate, lies and defamation of the Sun, the Mail and the rest. That isn’t a free press its psychological warfare against the public #BBCQThttps://t.co/nsq9SfMsUv

— Aaron Bastani (@AaronBastani) February 22, 2018

These themes resonated because they were so deeply entrenched in the collective imagination. Twenty-first century Islamophobia evolved directly out of the ‘Orientalist’ racism of nineteenth and twentieth century European colonial elites, which had permeated extensively into the wider culture and, like other racisms, established itself as an underlying ‘common sense’. Racism, in other words, is an embedded, structural feature of international politics. Furthermore, its structures are indivisible from those of state and economic power relations.

This has been true from the very birth of the modern world system that was created by capitalism and colonialism. Consider the familiar image of early capitalism, with the bourgeois owner of the textile mill exploiting the proletariat of a Lancashire town. This picture is incomplete without the slave labour in the US that produced the cotton for the mill, or the captive markets in south Asia into which the finished products were sold. It was notions of ‘race’ that justified the enslavement of Africans and the conquest of India, and – in these and many similar instances – played a structuring role within global capitalism from the outset, and through every subsequent stage of its development.

Today, racialising motifs long in circulation are ready and available to be reanimated for the new Cold War. Juxtapositions between US democracy and authoritarianism in China will easily fold themselves into familiar themes of ‘western values’ versus ‘Oriental despotism’ as politicians, journalists and academics feed the new geopolitical antagonisms through their pre-existing intellectual frames. As Sanders notes: “It is no surprise that today, in a climate of relentless fear-mongering about China, the [United States] is experiencing an increase in anti-Asian hate crimes”. A further revitalisation of western belligerence and self-satisfaction on the global stage is also to be expected, with a mix of foreseeable and unforeseeable consequences, none of them good.

Conversations about racism often focus primarily on domestic policy. But racism is a global issue, and for centuries has played a significant role shaping capitalism and the inter-state system. Racialised power structures are complex, connecting a vast terrain spanning cultural representation, political discourse, class struggle, state repression, war and geopolitics. These structures have never remained static, and will continue to evolve over the coming years.

David Wearing is an academic specialist in UK foreign policy and a columnist for Novara Media.