It’s High Time Britain Fed Itself

But that won’t happen until land is held in common.

by Kai Heron

5 August 2021

Last month, a month’s worth of rain fell in just 24 hours across parts of London, triggering flash floods and prompting evacuations. Between gasping at footage of flooded tube stations and Uber drivers taking to the pavement, there was just enough time to ask what climate chaos will mean for the UK. Will dangerous and unpredictable weather be the new normal? Yes, absolutely. Will London experience more floods before the summer’s end? Probably, if recent weather warnings are to be believed. Is the UK a good place to ride out the collapse of civilisation as we know it? Well, yes, according to a study released last week by scholars at the Global Sustainability Institute at Anglia Ruskin University.

The study compared the resilience of 20 developed countries to near or mid-term civilisational collapse, and found the UK was one of the five most likely places to survive as a “node of persisting complexity” in a sea of ecological devastation. Countries were evaluated on three criteria. First, a country’s “carrying capacity”, understood as an effect of a country’s arable land area per capita compared to the land required to provide at least a subsistence diet for all. Second, a country’s isolation from large external populations that could be “subject to significant population displacement” – climate refugees, in other words. Third, a country’s domestic energy supplies and manufacturing capacities.

The UK and Ireland are among five nations most likely to survive a collapse of global civilisation, researchers have said https://t.co/MngIIYxsOi

— Sky News (@SkyNews) July 29, 2021

Since the UK is an island with what the study calls “abundant indigenous renewable and non-renewable energy sources”, it scores highly on criteria two and three. On carrying capacity, the UK fares less well, only just managing to provide a subsistence diet for all.

In its scholarly and unimpassioned way, the study paints a grim picture. The UK dodges civilisational collapse – but only by becoming the real-life manifestation of John Lanchester’s dystopic novel The Wall. The UK is transformed into a fortress island, defending its chosen people from the starving, the desperate and the displaced. It’s a heady mix of eco-nationalist isolationism and eco-apartheid. Hardly a desirable outcome.

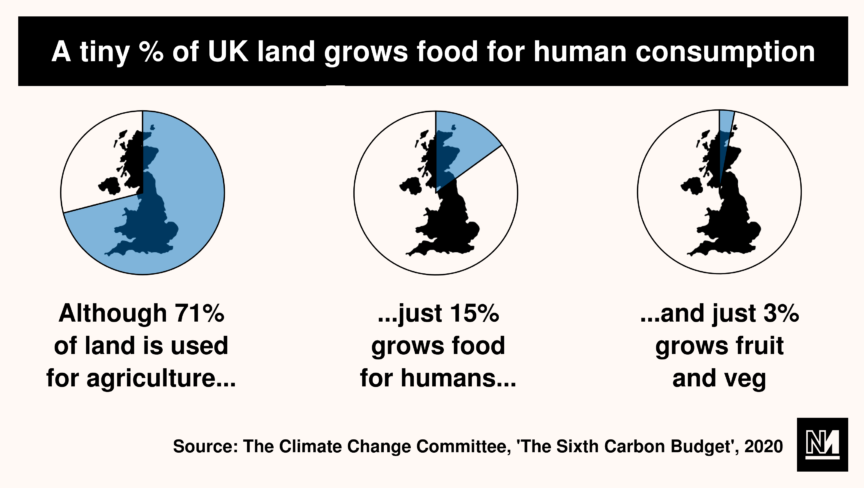

But setting aside the UK’s geographic isolation and abundant energy supplies, it’s debatable whether the UK – as it currently exists – could in fact feed itself. The study’s authors correctly note that 71% of the UK’s landmass is used for agricultural purposes of one kind or another, but they fail to take into consideration the UK’s long history of caloric dependence on the forests, soils and labour of its colonies and former colonies. Or the fact that Britain’s landscape is managed in the interests of just a few large landowners. For the UK – and the world – to mitigate the worst effects of climate chaos, we need large-scale land reforms.

Who feeds Britain?

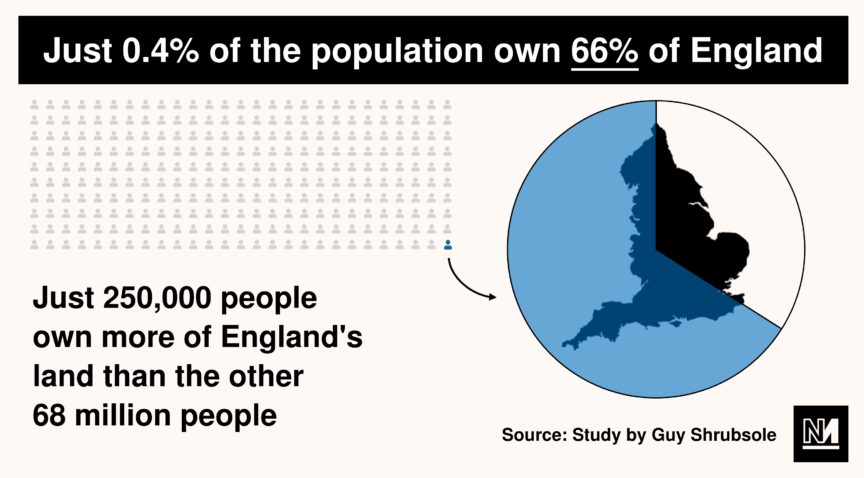

In his unmissable study of English land ownership, Guy Shrubsole finds that two thirds of England is owned by just 0.36% of the population. Around 30% of the country is owned by inheritors of feudal estates – the aristocracy and the monarchy – while 17% is owned by corporations, hedge funds and speculative investors. What’s more, Britain’s unequal patterns of land ownership have been with us for centuries. Many aristocratic families who today own vast tracts of Britain can trace their territorial claims all the way back to the Norman Conquest of 1066. It’s because Britain’s land has long served the interests of the few at the expense of the many that Britain seems incapable of building a climate resilient food system.

Anti-imperialist scholars Utsa and Prabhat Patnaik show that since at least the 1770s, it has been cheaper for Britain to rely on the lands and labour of its colonies and former colonies to feed its population. Conventional wisdom – of the kind my generation was taught in secondary school history classes – has it that British industrialisation was driven by domestic gains in agricultural productivity achieved in the 1700s via enclosures and the implementation of modern agricultural practices. The Patnaiks turn this history on its head. Their revised data shows that per-head agricultural output in the UK declined between 1750 and 1800, and remained stagnant between 1800 and 1820. This shortfall was made up for by Britain’s slave plantations and colonies. By 1800, the colonised Irish population, for example, was contributing 11-18% of England’s entire consumption of meat, wheat and butter.

UK industrialisation was not, therefore, a domestic affair. It was fuelled principally by the large-scale import of food and raw materials from Ireland and the UK’s colonial possessions in the West Indies and India. This cheap imported food reduced the need for agricultural labour in the UK, depressed domestic labour costs and increased profits for emerging capitalist industry.

Today, Britain’s agricultural landscape and consumption habits still bear the scars of this import-driven, colonial model of development. Though 71% of the UK’s landmass is used for agricultural production, just 15% is used to grow crops for human consumption and only 3% used to grow fruit and vegetables. The UK produces just 12% of its annual fruit consumption, leaning on Europe and Global South for the rest. 22% of British agricultural land is used to grow livestock feed crops, while grassland for livestock accounts for the remaining 63%. The 85% of UK land used to produce animal products contributes just 32% of the UK’s total caloric intake.

In short, most of the UK’s perishable goods, including fresh fruit, vegetables, coffee, tea, oils, animal feed and flowers, are acquired from the fields and seas of developing countries via super-exploited labour, or by precarious seasonal immigrant labour in Europe. This is all controlled by supply chains managed by giant agribusinesses located in the capitalist core.

Land reform now.

The Global Sustainability Institute’s Study excluded the role of the Global South and super-exploited labour in developing and feeding the 20 countries it compared. But to mitigate the worst effects of ecological collapse, we need to think relationally and internationally. The question of who owns British land and how Britain will provide itself with a climate resilient food system far into the future is intimately related to the issue of who owns land in the Global South, who benefits from the land, and how Southern nations can achieve national self-determination and food sovereignty.

This coming Monday will mark the one-year anniversary of protests by Indian farmers against prime minister Narendra Modi’s policies of food liberalisation. These protests, and similar land occupations across Africa and the Americas, need to be seen as the direct effect of the UK and the capitalist core’s historic and contemporary patterns of land ownership, land use, production, and consumption.

Securing food sovereignty – or as close to it as possible – in the UK is an admirable goal. Not as a contribution to building fortress Britain, but as a means of achieving a climate resilient food system that can provide nutrient-dense food for everyone in the UK while alleviating pressure on the Global South’s lands and labour. Were food sovereignty to be attained by implementing agroecological farming practices, the UK’s food system could also contribute to boosting our dwindling biodiversity while drawing down large quantities of carbon and cooling the planet in the process.

None of this is possible, however, if a minority owns what should be held and managed in common. To avert climate chaos, we need land reform in the UK – and beyond.

Kai Heron is a lecturer in politics at Birkbeck College, University of London.