Keir Starmer Is Just As Dishonest As Boris Johnson

While the prime minister is honest about lying, the Labour leader still claims to be telling the truth.

by Aaron Bastani

29 September 2021

A strange prospect has reared its head in recent months, its arrival so unlikely that even the most dogged of Starmer-sceptics could never have predicted it.

Over the weekend, as Labour’s annual conference got underway, this previously faint suspicion suddenly came through in high definition: Keir Starmer – a man who constantly appeals to decency and principle – appears to be no more honest than Boris Johnson. Indeed one could argue Starmer is less trustworthy than a prime minister whose calling card is caddish misbehaviour.

This may sound absurd, like the nonsensical grumblings of a leftist with a grudge, but allow me to explain.

When it comes to honesty there are three kinds of people. The first are honest and upstanding, they generally stick to their word and try not to deceive others. Although, of course, deceit may happen on occasion, they try their best to keep dishonesty to a minimum. When they stray they admit it.

The second kind are dishonest people who are open about the content of their character – individuals who are, in short, ‘honest liars’. Paradigmatic here is Silvio Berlusconi, the former Italian prime minister, who once claimed to be the “Jesus Christ of politics” because he makes sacrifices “for everyone” only to later concede, when investigated on charges of corruption, that he was not a saint and “you’ve all understood that”. In this regard, the media tycoon was the template for Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, with all three never guilty of hypocrisy – that cardinal sin in politics – because they never claimed to be honest in the first place. Unsurprisingly, many find such personalities reprehensible, yet others view them as a refreshing change and often amusing. Sure they lie, but everyone in politics does. That they are at least open about their moral failings means they aren’t really politicians at all.

The final category is the dishonest figure who claims to be a beacon of truth. While the likes of Berlusconi and Johnson are incapable of hypocrisy (and by extension shame) the problem for this kind of person – think Hilary Clinton or Matteo Renzi – is that, once caught out, the incongruity of their words and actions renders them entirely inauthentic. It is in this final category that Starmer now finds himself.

This is a particular problem for the Labour leader, which will only get worse because he has leaned so hard into presenting himself as principled. This often bordered on hyperbole, such as when his leadership campaign delivered hundreds of thousands of posters adorned with nothing but his grinning face and the words ‘integrity’, ‘authority’ and ‘unity’. In the early months of 2020, Starmer insisted his was a ‘moral socialism’.

The sell was obvious at the time, a continuation of Corbyn’s policy agenda with Sir Keir’s establishment credentials thrown in to make them more palatable. The axis on which all of this turned was the combination of moral rectitude and political nous, the best of Corbyn and Blair. With the passage of time, it is increasingly clear that Starmer has neither.

Ten Broken Pledges.

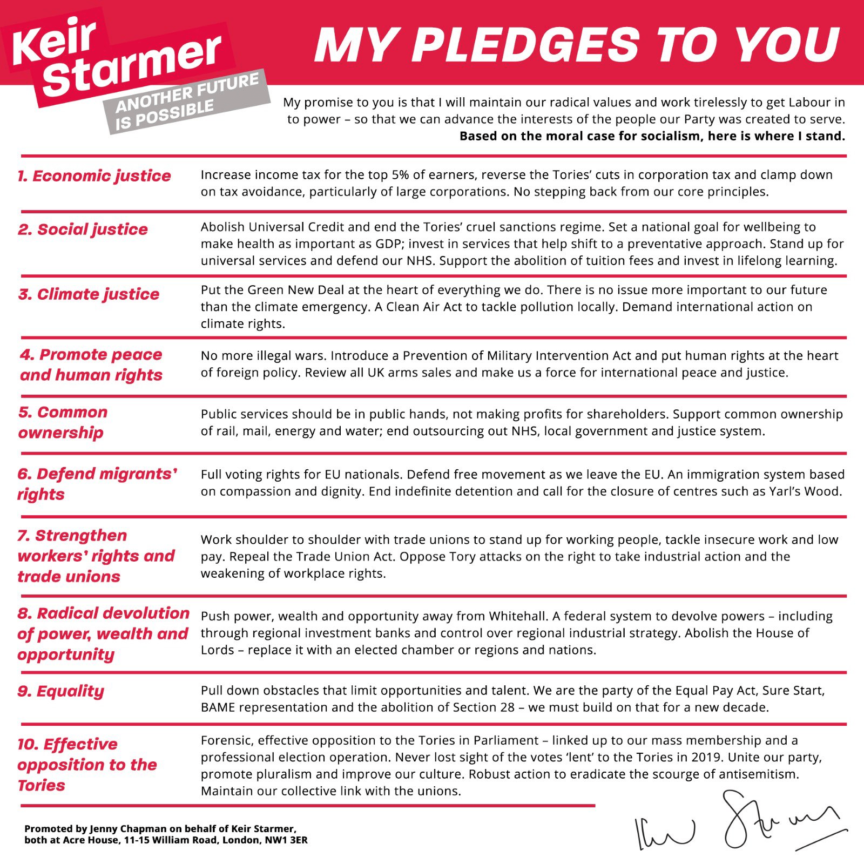

The central document of Starmer’s leadership bid was his ‘ten pledges’, a list of promises he made to Labour members in 2020.

The first pledge touches on ‘economic justice’, with the very first line of the document stating Starmer would increase income tax for the top 5% of earners as well as corporation tax. And yet when Rishi Sunak did precisely that earlier this year, raising tax on corporate profits from 19% to 25%, Starmer called on his MPs to abstain. On income tax, the party appears to be following a similar path, with shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves telling the Sunday Times that she had no plans to increase income tax.

That same morning, appearing on the Marr Show in the face of a looming energy crisis, Starmer was asked whether he favoured nationalising the ‘big six’ energy companies. After eventually replying that he did not, Andrew Marr proceeded to ask if that signalled the ditching of his fifth pledge which called for public services to “be in public hands”, with common ownership applied to “rail, mail, energy and water”.

Sir Keir Starmer tears up one of his Ten Pledges on public ownership live on #Marr#Marr: “Will you Nationalise the Big 6 Energy Companies Yes or No?

Sir Keir: “No” pic.twitter.com/8T8Ln8cPki

— Martin Abrams🌹😷✊🏼 (@Martin_Abrams) September 26, 2021

Any reasonable person could see Starmer had reneged on his promise on live TV, and yet the former barrister continued by saying common ownership doesn’t necessarily mean nationalisation. Does this mean he supports turning giant energy companies into co-ops? For some things that might be a wise decision, of course, but for a natural monopoly like energy, it is not.

Regardless of what Starmer means by common ownership that is not nationalisation, it is clear he is reneging on commitments he made in 2020 at breakneck speed. In leadership hustings, he explicitly said he agreed with policies such as renationalising energy. A politician who breaks promises isn’t new, of course, but it rather dilutes appeals to courageous truth-telling. Even while abandoning such policies, on television, Starmer claimed he was not.

Liar lair pants on fire. Lied to get elected. Swindler pic.twitter.com/tCAkkMqLls

— Matt Zarb-Cousin (@mattzarb) September 26, 2021

But Starmer’s habit of broken promises extends beyond policy u-turns, residing at the heart of his leadership style. One example of this was when the Palestine Solidarity Campaign found itself briefly banned from appearing at a Young Labour event because it was too ‘controversial’. After public remonstrations by Jess Barnard, Young Labour Chair, that decision was reversed. This was all the more remarkable given Starmer himself had spoken at a PSC event as recently as 2015. Were a member of his shadow cabinet to speak alongside anyone who had published a book titled ‘The Myths of Zionism’, as Starmer did then, it’s doubtful they’d last very long.

In a similar vein, Starmer claimed during the leadership election that Corbyn had been ‘vilified’ by the media. Since succeeding him the chances of the Labour leader repeating such an obviously true statement have become unthinkable.

Yet most dishonourably of all, it was Starmer who inflicted the greatest injustice on his predecessor when he chose to suspend him for remarks which, some allege, were agreed in advance. Even if they were not, however (the leader’s office maintains as much) Starmer claimed to have been involved in the decision before claiming, at other times, that he was not. What was clear was that Starmer said different things to different audiences at different moments – the only problem for him was that he did all of this on television and radio.

Over the following weeks, Starmer’s office reputedly negotiated a way back for Corbyn, but u-turned each time an agreement was in sight. Writing in the Guardian, Len McCluskey has explicitly stated that Starmer had “reneged on our deal”, and even after Corbyn was re-admitted as a member by an NEC panel, Starmer withdrew the whip from him. The man who said his predecessor had been savaged by the media was now the orchestrator of arguably his greatest humiliation.

Finally came the events of recent weeks when, at the last minute, Starmer and his allies on the Labour right tried to bounce party conference into re-introducing an electoral college to elect any successor. Having never previously mentioned this – as either an MP or party leader – Starmer suddenly declared it mission-critical if Labour was serious about power.

This isn’t remotely true, of course particularly since the Tories, Lib Dems and SNP all have ‘one member, one vote systems,’ and Labour’s most successful leader, Welsh first minister Mark Drakeford, was chosen using this method. But a coherent reason wasn’t necessary and all purported reasons concealed, again, an obvious deceit: the point here was that Starmer’s replacement would not come from the party’s left, even if that meant scrapping the very system which allowed Starmer himself to win.

In what can only be described as an episode of supreme amateurism, Starmer had to dilute such reforms to merely increasing the number of nominations required to get on the ballot. At conference this passed – just – and had Unison voted against it, Starmer would have lost. In a context which can only be described as vote-rigging – with delegates informed of suspensions and expulsions as late as Friday evening – this meant Starmer looked as weak as he did mendacious. Unlike with Trump, many ‘centrists’ didn’t seem to mind, however, presumably because they think subverting democracy is acceptable if you agree with the people doing it.

Yet such actions aren’t lost on the majority of people. While Boris Johnson has constructed a career on mistruth, from claiming children under eight are banned from inflating balloons to the EU regulating for one size of condom, he has always performed his dishonesty with lies so bizarre they raised a smile for every scowl. Johnson is not a virtuous man, nor does he claim to be. This is a major difference to Starmer.

The electoral success of Boris Johnson demonstrates that, like it or not, the electorate doesn’t mind if the PM is a liar. What they can’t stand, however, is a hypocrite who pretends otherwise. That, in a sentence, is the Labour leader’s morality. It may prove politically fatal.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.