How We Won: The Activist Deceived By a Spycop Who Took on the Met

'You can’t trust anyone anymore.'

by Alex D King

20 October 2021

“This isn’t about the undercover police officer who deceived me,” says Kate Wilson, an activist who was duped into an intimate relationship with an officer for two years in the 2000s. “He’s a pawn in the operation; he isn’t the one setting the strategy, or deciding to have the undercover operation in the first place. It has always been about getting the people making those decisions, rather than the man I knew—or didn’t know.”

For two years, Wilson was deceived into a sexual relationship with undercover officer (UCO) Mark Kennedy. Kennedy had been deployed by the police’s Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) to spy on a community space in Nottingham where Wilson had been involved in organising direct actions.

In 2011, Wilson, along with seven other women deceived into relationships with spycops, sued the Metropolitan police.

The Met denied any liability for four years, but settled with the women in 2015 when it looked like they’d have to disclose potentially explosive police reports.

Police spies are lying in a court of law about their conduct while undercover inside social movements. Why is the judge still believing anything that comes from their mouths? They were paid to lie and betray. #spycops https://t.co/1weKQO4EcK

— Gerrah Selby (@GerrahSelby) October 25, 2018

Unwilling to give up her fight for justice, Wilson took her case to the Investigative Powers Tribunal (IPT), the judicial body responsible for hearing cases concerning public bodies’ use of covert investigatory powers.

Ending a further four year battle, the IPT finally ruled that the Met had, in fact, violated several of Wilson’s human rights.

BREAKING:

Court rules in favor of Kate Wilson and finds that #SpyCops infiltration of campaigns is both “unlawful and sexist” #InstitutionalSexism #MeToo

Brilliant historic victory by @fruitbatmania and her legal team pic.twitter.com/lnOnQDsLaT— Dave Smith – Blacklist Support Group (@DaveBlacklist) September 30, 2021

The ruling sets a huge legal and political precedent—establishing that this was indeed state-authorised abuse, and giving the judiciary independent oversight of the police.

Thread🧵on today’s momentous Investigatory Powers Tribunal ruling that the deception by undercover police officer Mark Kennedy, who deceived Kate Wilson into a long-term, intimate relationship, was a fundamental violation of her human rights #spycops https://t.co/MExPCSVgJ8

— Netpol (@netpol) September 30, 2021

Wilson’s victory was not just a personal win, but a success for the many women who have also been tricked into relationships with spycops, according to Lisa*, another activist who was deceived into a relationship with Kennedy, and who worked with Wilson on the case.

“The outcome of Kate’s case is hugely relevant for me,” she says. “We all felt as if it was our case that she was winning.”

This is an enormous achievement for Kate, but also for all of us who have been fighting for over a decade to expose the institutional nature of what was done to us by the police, and to others before us. Finally a court has listened #spycops https://t.co/eN3OwrQNqF

— Lisa Lân (@JustLisa2010) September 30, 2021

‘A shy, working class, new guy.’

When she first met Kennedy in 2003, Wilson was working on a campaign to oppose the G8 summit at the Sumac Centre, a community space in Nottingham.

“Mark came along to a political meeting of the Nottingham Assembly of Subversive Associations,” she recalls. “He presented himself as a shy, working class, new guy. We sat next to each other. We got chatting.”

It wasn’t long after that Wilson and Kennedy entered into a relationship. Wilson suspects that Kennedy had been briefed on her life story in order to enable their swift enamourment. “Mark wasn’t the first UCO infiltrating our community; I knew his predecessor.

“The police train UCOs to mirror people’s interests,” she explains. “It’s hard for me to know whether I found Mark attractive because of his personality, or [because of the] information that he had about me gathered, which he knew would get my attention or make me feel comfortable. He lied about where he was from; he said he was from a neighbourhood close to where I grew up, which wasn’t true.”

After two years together, Wilson and Kennedy split up in 2005—although Wilson never suspected he was a spycop.

But Kennedy wasn’t quite ready to hang up his boots. In that same year, he entered a relationship with Lisa, another environmental campaigner in Wilson’s circles, who met him when he made a visit to Leeds where she lived at the time.

Lisa was spied on for 6 years by a man she thought was her partner.

The inquiry into the Met Police operation, set up in 2015, is expected to go on until *2023*.

You can read the interview here: https://t.co/sRnZkj94oZ

— Rebecca Wilks (@WilksBecca) October 1, 2021

During this time, Kennedy continued to inform his handlers on the activists’ actions. In April 2009, he informed the police of activists’ plans to break into a Nottinghamshire power plant, with the police arresting 114 activists – including Kennedy – as a result. A week before he and 26 activists had been told they would be charged for their attempt, the case against Kennedy was dropped – the other 25, however, were charged.

This raised the suspicions of the activists in the circles Kennedy had been infiltrating, and soon his handlers told him that the surveillance operation was being dropped. He was, they said, to tell the activists that he was leaving to visit family in America – after which he could return to the force.

Kennedy did just that. However, he left the Met in 2010, saying that he’d become a “pariah” in the police as a result of his undercover work, losing many of the competencies he needed for frontline policing but not being supported to reskill.

Interview with Richard Chessum on @novaramedia – a man whose entire working life has likely been shaped by police surveillance and spycops.

These appalling practices, including sexual assault, will see the disinfectant of sunlight over the coming years. https://t.co/dUuIi0aCrf

— Aaron Bastani (@AaronBastani) July 6, 2021

Despite this, astoundingly, Kennedy then returned to the Nottingham activists presumably to continue his relationship with Lisa or to better manage his exit from activist circles. However, in July that year, while holidaying together, Lisa stumbled across a passport in Kennedy’s car. “It said he had a different name, that he had kids.”

Lisa confronted him but Kennedy said he had many passports from his drug-dealing days. “Then a few months later,” Lisa recounts, “I heard that somebody who’d been involved in Reclaim The Streets, Jim Boyling, had been a UCO, and that he’d had a relationship with an activist. That was when I had an inkling that I could be in the same position.

“I decided to do some research,” she explains. “I found out there wasn’t a birth certificate for the person I thought I was in a relationship with. His kids’ birth certificates said he was a police officer—so did his marriage certificate.”

Lisa presented her research to her comrades, and in the early hours of the morning on 21 October, 2010, she and five other activists outed Kennedy. He confessed, and they demanded he make a public statement. But unwilling to do that, Kennedy ran away, finding himself disowned both by the protestors and the police.

‘You begin to doubt everything.’

Discovering she’d been in a relationship with a spycop had a devastating impact on Wilson’s mental health, and on her ability to not only trust others, but to trust herself. “It gets into every single corner of your life,” she says. “You can’t trust anyone anymore. You don’t know what’s going on. You don’t know if your beliefs were your own.”

Lisa also experienced long-lasting trust issues. “I’ve not been able to form any new romantic attachments in the decade since I discovered Mark’s true identity, and the idea of falling in love again and trusting someone with that love is still a frightening prospect,” she laments. “I’ve not been able to be involved in campaigning work in the way that I used to—that was a huge part of my identity that disappeared overnight.

“I’ve also missed the opportunity to start a family as I spent my prime fertile years in a relationship with someone who was adamant he didn’t want children—because he already had them.”

And as if hearing your partner has been lying to you isn’t bad enough, Lisa also had to grapple with the fact that Kennedy’s deceit had been sponsored by the state.

She recounts a time in the relationship when she asked Kennedy to come with her to scatter her late father’s ashes. He claimed he couldn’t make it because of work commitments, leading the pair to “fall out”.

When Lisa read the police reports years later, however, she could see that Kennedy had asked his supervising police officer to authorise him to go – but they’d said no.

Reading these documents, Lisa had the chilling realisation that her life in those years had not been of her own making; it had been directed by the inscrutable decisions of faceless police officers. “I didn’t have free will,” she reflects. “My choices were passed up the chain of command—who knows what was behind those decisions. I don’t know, and I probably never will.”

‘Start throwing rocks.’

Following the confrontation with Kennedy, in October 2010 Lisa went public with her story, which quickly blew up in the press.

Lisa’s going public encouraged others to come forward. A number of women—Wilson among them—began reaching out to say that they’d had similar experiences.

Donna McLean was deceived into a long-term, engaged to be married, cohabiting relationship by #SpyCops officer Carlo Soracchi. Like many such women, she’s had her identity protected & has been known as ‘Andrea’. This week she’s relinquished her anonymity. https://t.co/BGIQWCIRNU

— COPS (@copscampaign) July 17, 2020

Realising that her situation was far from unique, Lisa helped coordinate a group who were willing to bring a claim against the police. “[Lisa] rang me seven days before the Human Rights Act deadline saying they were bringing a case,” says Wilson, who then joined the group.

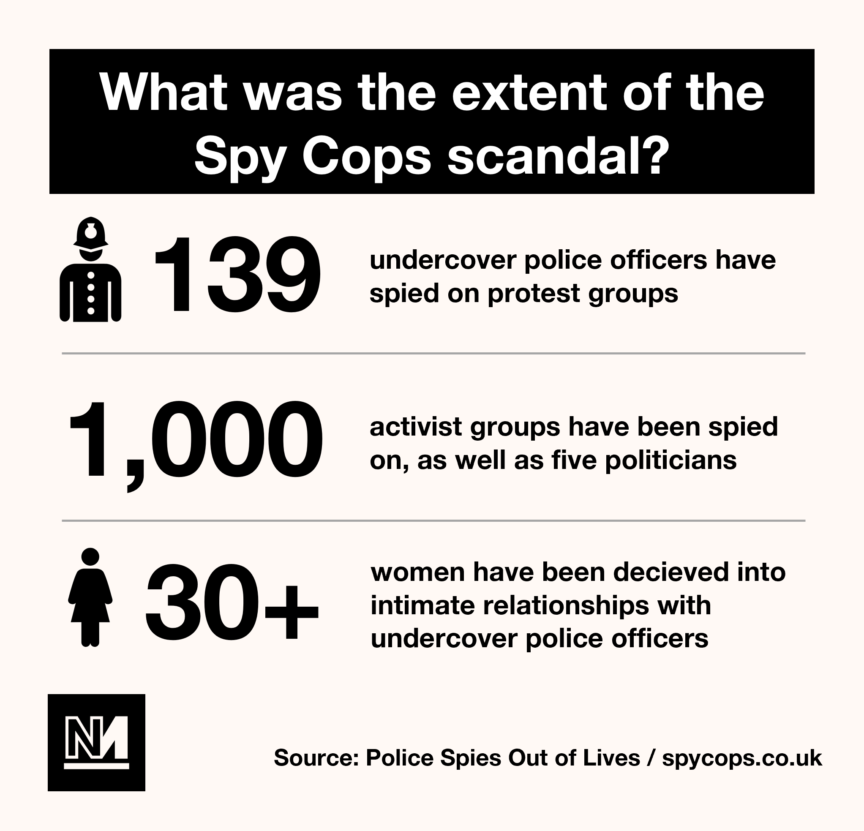

In 2011, eight women deceived into sexual relationships with UCOs sued the police for deceit, assault, misfeasance in public office, and negligence.

“Right from the beginning,” Lisa says, “when all eight of us brought this case, we were an invaluable source of emotional support to each other. We got the politics of what we were trying to do, discussing early on what our aims were and what we were trying to achieve.”

Unsurprisingly, the Met spared no effort in trying to have the women’s cases struck out by keeping any evidence of state-authorised deception out of the public eye.

The claimants, however, were determined to make sure the police were held to account. “There’s a line from one of my fellow campaigners,” Wilson quips, “‘keep shooting until you run out of bullets—then start throwing rocks.’ We tried every angle possible to get around [the Met’s attacks].

The police’s initial strategy had been to neither confirm nor deny whether Kennedy had been a spycop, thus enabling them to dodge pleading guilty or innocent to the accusations made against them, and licencing them to deal with the wrongdoing internally.

“They thought the case shouldn’t go to court because it dealt with state secrets,” Wilson explains, “and they said they couldn’t defend themselves because they weren’t going to talk about what happened”.

The women, however, argued that the police had to respond—that their case had to go to a trial to dismantle police impunity. “The police shouldn’t be able to police themselves,” Wilson argues. “It’s not enough for the police to authorise their own operations, commit all kinds of abuses, and then turn around and say they’re sorry—and all of that happens in-house. Taking this to court is a way of getting independent oversight.”

It was a convincing argument—and one that ultimately compelled a judge to order the Met to respond to the women’s allegations. “They had to be ordered by the court to even serve a defence,” says a wry Wilson.

‘One bad apple?’

The case finally entered the High Court as a civil claim in 2011. But now, the police changed tack, pivoting from their previous stonewalling tactics to admitting partial liability.

“They denied everything in my civil claim, right up to when we went to court and we were going to start discussing disclosure of evidence,” Wilson says.

The Met then withdrew its defence, and accepted partial liability. “They admitted the parts of the claim that related to the sexual relationship and which related to Mark,” says Wilson. “This meant that they admitted to the relationship infringing my right to privacy and that it was inhuman and degrading treatment.”

This was an important but ultimately partial victory, because admitting liability meant the police could withdraw their defence, avoid disclosing evidence to the claimants and make unfalsifiable claims.

“The civil courts establish wrongdoing and settle damages,” explains Wilson. “So if the defence admits liability and offers to settle damages the details of what happened don’t matter.”

This tactic served the police well; in November 2015 they withdrew their objections, offered the claimants compensation, and avoided disclosing the evidence.

‘Right up the chain.’

Despite this, the women weren’t giving up on making public what had happened to them. Their original claim had contained potential human rights abuses, and these parts of the claim sat with the IPT until that civil claim had been resolved in the High Court.

For various legal reasons, some of the women couldn’t pursue the case after the High Court, Lisa explains. “Anyone whose relationship had taken place before the Human Rights Act was created wasn’t able to make their human rights claims. That cut out five of the women.”

Legal technicalities surrounding the times and conditions attached to settlements then meant two of the remaining three women weren’t allowed to take the case any further, leaving just Wilson.

Absolutely. And there are many of us (well over 50 women that we know about, lots more who don’t know yet).#spycops #WeStandWithKate https://t.co/fKTe4zCpoU

— Donna McLean (@Donna__McLean) April 20, 2021

When she made her claim in the IPT in 2018, the police tried to do the same thing they’d done in the High Court. “They admitted the parts of the claim that related to the sexual relationship and which related to Mark,” Wilson recalls. “So they admitted the relationship infringed my right to privacy, and that it was inhuman and degrading treatment. But Mark Kennedy was a ‘bad apple’.”

The Met then rolled out the big guns to hold the position that the police would pay compensation and apologise to the claimants, but “based on the evidence” Kennedy was just a bad apple.

The deputy commissioner of the Met, Sir Stephen House wrote a statement in which he said he’d reviewed Wilson’s reports and had concluded that no senior police officers had known about the deception, much less authorised it. This was the police’s position in the case, says Wilson.

“We had this absurd situation where I was telling the police they couldn’t withdraw their defence because my claim included either/or suppositions. Either senior police officers were complicit in my sexual assault, or they were negligent in the extreme. The police were effectively turning around and just saying ‘yes’. Well, which one is it?”

Crucially, however, this didn’t work in the IPT because human rights law is concerned with learning the lessons of past mistakes rather than simply settling damages.

“As the Greenfield case establishes,” Wilson explains, “the main purpose of human rights law is to establish whether breaches of human rights have happened so that lessons can be learned and they don’t happen again.

“In the courts interpreting human rights law, the details of what happened matter,” says Wilson; if you discount them, “the state can’t take measures to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

“It makes a big difference to the public and to the state whether it was just a case of ‘one bad apple’ who gamed the system for his own personal gratification, or whether it went right up the chain.”

Wilson, who represented herself in court because there was no other option in light of the police conduct of the case, demanded to see the evidence so she could give her own interpretation of it. The IPT obliged, ordering the police to turn over 12 years’ worth of reports.

Intriguingly, the police then withdrew House as a witness. “It would’ve been safe for him to be cross-examined in court without us seeing the documents,” Wilson posits. “But once we had them we could’ve embarrassed him.”

For instance, House had concluded that other officers hadn’t known about Kennedy’s relationship with Wilson. “But when we looked at the documents, we could see they were having meetings to discuss the implications of me moving out of the house, whether Mark should put my name and address as his next of kin for whatever form he has to fill out.

“It would’ve been quite a spectacle to cross-examine a senior police officer who’d basically written a statement under oath saying that he believed they didn’t know!”

‘Disturbing and lamentable failings.’

Earlier this month, the IPT handed down its landmark ruling that the Met had breached a number of Wilson’s fundamental human rights, guaranteed by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and transcribed into UK law in the Human Rights Act.

The IPT looked at evidence relating to the sexual relationships Kennedy had with Wilson and a number of other women, and the widespread practice of UCOs deceiving women into intimate relationships.

It concluded that the Met had violated Wilson’ human rights, including her right to live free from inhumane and degrading treatment, her right to private and family life, and her right not to experience sexist discrimination; as well as her freedoms of expression, assembly and association.

📢 BREAKING – COURT RULES UNDERCOVER POLICING OPERATION AGAINST PROTEST MOVEMENTS WERE ‘UNLAWFUL AND SEXIST

We are so proud of @fruitbatmania who has won her epic ten year battle against the @metpoliceuk#spycops https://t.co/j9L4TT204d— Police Spies Out of Lives (@out_of_lives) September 30, 2021

Significantly, it also determined that Kennedy had not been a ‘bad apple’ but a product of the policing system.

“This is not just a case about a renegade police officer who took advantage of his undercover deployment to indulge his sexual proclivities,” it ruled. “Our findings that the authorisations under RIPA were fatally flawed and the undercover operation could not be justified as ‘necessary in a democratic society’…reveal disturbing and lamentable failings at the most fundamental levels.”

In a comment, the Met told Novara Media it would “accept and recognise the gravity of all of the breaches of Ms Wilson’s human rights as found by the Tribunal,” and both the Met and NPCC “unreservedly apologise[d] to Ms Wilson for the damage caused, and the hurt she has suffered from the deployment of these undercover officers.”

There’ll be a hearing before the IPT at a later date to consider an appropriate remedy for Wilson.

‘This isn’t just about me.’

Reflecting on her victory, Wilson is keen to emphasise that, far from achieving it on her own, collective action was vital in her success. “There’s been a lot of focus in the media on me as a lone woman against the state because they like that idea. I’ve become a bit of a figurehead.

“But that’s not even close to being the whole story. It’s a huge community of people across a massive political spectrum who have been affected by this and who I’m working with.”

A support group, Police Spies Out Of Lives, was set up to provide legal support for the women bringing claims. Soon a number of women were volunteering their time to interpret the evidence and form arguments.

“By the time I was a litigant in person, I had thousands of pages of complex redacted police documents which I had to analyse,” Wilson says. “The volunteers worked with me on making those arguments.

“I got lawyers in the end but that was only about three months before we went to trial. It would probably have been impossible for them to come on board so late in the day if it hadn’t been for the work done by the community.”

‘We’re suspicious of the wrong people.’

Wilson’s victory over the Met provides important lessons for activists in terms of knowing how to identify spycops and how to hold the police to account for human rights abuses.

A key argument for Wilson’s case against the police was that Kennedy’s invasion of Wilson’s life didn’t just constitute a violation of her privacy, but undermined democracy itself.

This was because Kennedy, like many other spycops, made himself the lynchpin of the organisation he’d been infiltrating. “Anybody who was in a group with these UCOs will tell you that they weren’t casual bystanders who came along to meetings and took the back seat,” Wilson relates. “They’d been the treasurer or the president. They were at the centre of things.

“Mark was sometimes one of the first people to know about an action, and then he’d go out around the country to tell activists it was happening and get them involved.”

Wilson believes spycops’ involvement in activism serves to subvert democratic dissent. “I think they’ve been manipulating people’s ability to get together, the ways people think about stuff, the ways they approach stuff.

“They undermine people’s organising and ability to affect political change … it’s not just an infringement of your right to freedom of expression and freedom of association—it undermines the entire institution of democracy.”

Lisa believes this is one of the most important lessons for activists to learn from the case. “We’re always suspicious of the awkward ones or the quiet ones—you’d think, oh they’re a bit funny, I’m not sure about him.

“Actually, it was the person who was the most socially engaged who we should’ve suspected. We’re suspicious of the wrong people. It can only be helpful to show people what they’re really looking out for.”

But both Wilson and Lisa warn activists against paranoia. “Paranoia can have a chilling effect on people’s willingness to engage in political action at all,” Wilson says.

“That was actually our argument in court; it’s not just the direct manipulation that the police do by being involved in political campaigning, but just the knowledge that they’re doing that destroyed large swathes of the political movements that I was involved in. They were absolutely devastated by these revelations. Most of these groups no longer exist.”

Wilson recommends activists get in touch with the Undercover Research Group if they suspect someone’s a spycop. “Take it seriously—don’t think you’re not important—investigate it, try to get proof. But don’t spread fear, don’t damage your groups.”

‘Was my friend a spycop?’ Our guide to investigating suspicions, trying to find out if a comrade was an undercover police officer. https://t.co/8DmthyU5uB … … … #spycops download or order print copies. pic.twitter.com/Hcb2f9KlRE

— UndercoverResearch (@UndercoverNet) July 25, 2018

Lisa says organisers must learn from the case so that they – and future activists – can spot these trends in the future. “It’s about looking at these different cases and knowing how UCOs operate,” Lisa says. “That information’s going to empower people.”

Lisa hopes this judgment can be used in some of the campaigns to show why we need this Human Rights Act, and why we need to overhaul policing.

“With the conversation over the last week that’s been had around Sarah Everard — hopefully, both of these things together can now show that policing in this country is completely beyond reform, and needs a total rethink,” she argues.

“It’s not about law and order, it’s about crushing dissent. We’ve shone a spotlight on that with the hope that it can feed into this conversation somehow. The most important thing is for us to carry on campaigning.”

Alex D King is a freelance journalist based in Manchester.