Cop26 Is Little More Than a Cop-out

How many times can it be the ‘last chance’ to save the planet?

by Ell Folan

11 November 2021

With COP gatherings often hyped as the final opportunity to save the planet, 26 conferences later that same empty rhetoric is being pedalled – all while emissions continue to rise and the big polluters sit on their hands.

This year, it was Prince Charles who took up the gambit, labelling the gathering “the last chance saloon” for action on climate change, and urging world leaders to set aside their differences and agree a framework for action.

Indeed, climate conference after climate conference has been described in this way: COP25 was called the “last chance” to save the planet by WWF Japan’s climate lead; UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned COP24 delegates not to waste “our last best chance”; former president Barack Obama declared COP21 a potential “turning point”; and then prime minister Gordon Brown said as far back as 2009 that if no agreement was reached at COP15 then “it will be irretrievably too late” to act in future.

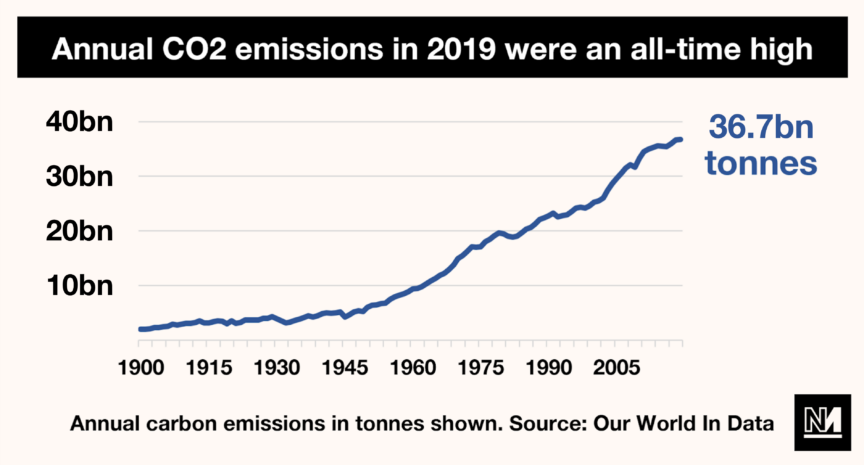

Despite so many summits being framed in these dramatic terms, you would have to squint to notice any material action resulting from them – even after the much-trumpeted 1997 Kyoto Protocol and 2015 Paris Agreement. In the three decades since world leaders first assembled at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, global carbon emissions have risen inexorably. Between 1993 and 2019, the world emitted 739 billion tonnes of CO2 – meaning that in those 26 years, we poured more CO2 into the atmosphere than the previous 90 combined.

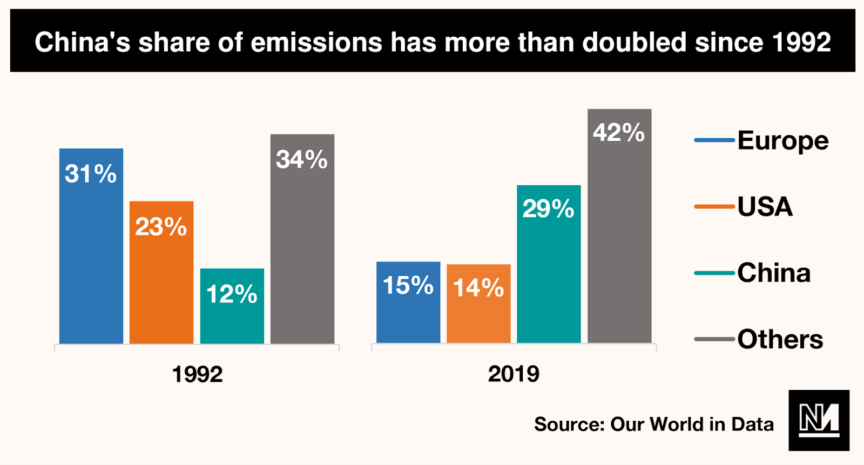

So who is responsible? Many would say China. Back in the 1990s, Europe and the United States were still the source of the majority of annual CO2 emissions (54%) whilst China was producing only 12%. By 2019, however, China generated almost as much CO2 as Europe and the US combined. These statistics often prompt commentators to hold China responsible for the rise in global emissions.

However, this is not the lesson we should be taking from those statistics, for two reasons. First, as much as 16% of China’s emissions are the result of creating products it exports elsewhere – often to the West. Second, the growth in Chinese emissions has driven unparalleled development, helping lift over 700m people out of extreme poverty.

This latter point is crucial. It is not as simple as blaming one relatively poor nation or making blanket demands for equal cuts in emissions across all countries. Rather, the challenge we face is how to equitably distribute emission cuts and still enable countries to raise living standards.

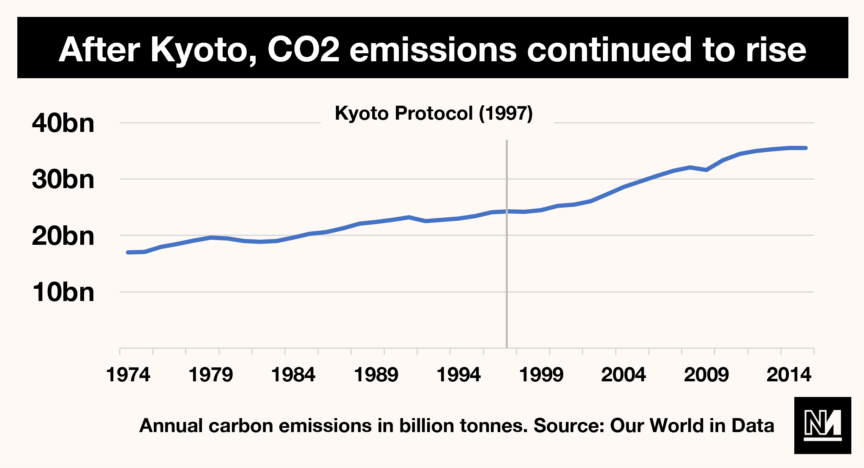

Despite numerous conventions and deals, the world has yet to meet that challenge. Take two notable examples: the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. Following Kyoto (which committed industrialised nations to reduce emissions), the Guardian labelled it a “historical deal”, whilst the New York Times called it “a landmark environmental policy”. Then-US Vice president Al Gore declared it a “vital turning point” in combatting climate change.

Yet despite these celebrations, you would be hard-pressed to notice any reduction in emissions resulting from the 1997 agreement. In the 18 years preceding the Kyoto Protocol, annual carbon emissions had risen by just 4bn tonnes. In the 18 years following the protocol, however, emissions rose by 11bn (from 24bn to 36bn).

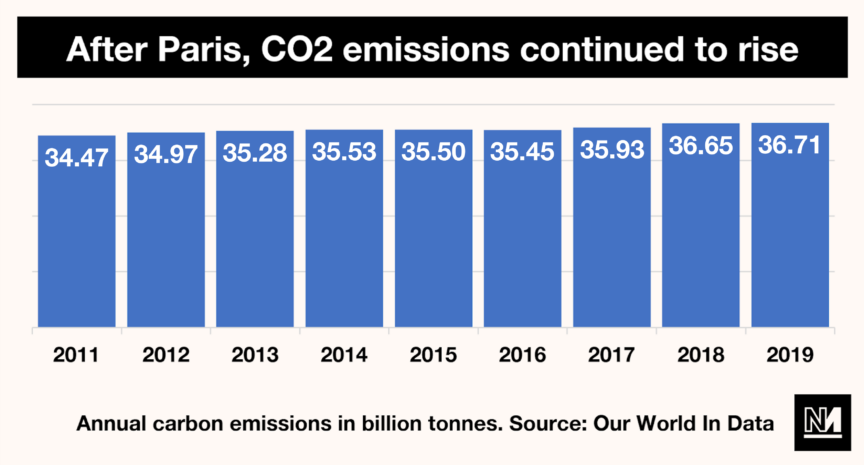

The same criticism can be applied to the Paris Agreement, which brought all nations together by asking them to submit climate action plans. The Washington Post, for example, called it “a landmark in the world’s response to manmade climate change”. Despite being lauded by world leaders, the agreement does not seem to have made any difference – again. Between 2015 and 2019, annual emissions rose by 1.2bn tonnes – yet in the four years preceding the agreement, emissions had risen by 1bn tonnes. Once more, the reality failed to live up to the fanfare and posturing.

These agreements have arguably failed for the following reasons. Firstly, the world’s economic system has created little incentive for profit-seeking businesses to invest in green technologies that were – until very recently – more expensive than fossil fuels.

Secondly, the non-binding nature of most agreements means that many countries simply rely on others to act, resulting in what economics professor William Nordhaus calls “pervasive free-riding”.

Finally, the US has repeatedly proven to be a stumbling block to the world’s progress: from refusing to ratify the Kyoto Protocol in the 1990s, to withdrawing from the Paris Agreement in 2018, to vetoing enforceable treaties, the USA’s efforts have been consistently sluggish. Even now, President Biden’s relatively moderate climate legislation is struggling to pass through a bitterly divided Congress.

Meanwhile, China has become a world leader in renewable energy.

These things can change – some more easily than others. Green energy has, in the past decade, become cheaper (in many cases) than fossil fuels – and governments must act to reduce these costs further. Meanwhile, as Nordhaus argues, attaching binding conditions to climate treaties could compel countries to actually act upon their commitments, though these have proven difficult to negotiate. At the same time, the US could – with enough internal and external pressure – act urgently and decisively to reduce its emissions through policies like a Green New Deal. Lastly, as citizens, we should make sure to prioritise lobbying and pressuring our own governments instead of relying on international summits.

Until these things start to happen, however, gatherings like COP26 will largely remain exercises in shifting blame. We desperately need our world leaders to do better than that.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties and a columnist for Novara Media.