The West Botched Cop26, Then Blamed China

The EU spent €13bn on new oil and gas projects during Cop26 alone.

by Aaron Bastani

18 November 2021

A hallmark of Conservative rule over the last decade has been the use of hyperbole to describe the mundane or conceal the disappointing. Consequently, when David Cameron oversaw an outsourcing boom it was labelled a ‘jobs miracle’. Departure from the EU, rather than a nuanced calculation, was presented as ‘unleashing’ a nation whose indolence was the result of continental meddling. Unsurprisingly, such patriotic puffery found its climax during the pandemic, when everything that Britain did, from test and trace to online learning for schoolchildren, was hailed as ‘world beating’.

Given Britain holds the rotating Cop presidency, similar feats of self-congratulation were always likely at Glasgow. The big names didn’t disappoint with the UK’s Cop president, Alok Sharma, describing the final deal as “historic” – despite being on the verge of tears and apologising after the gavel came down. Boris Johnson, with typical understatement, concluded it was “game-changing”.

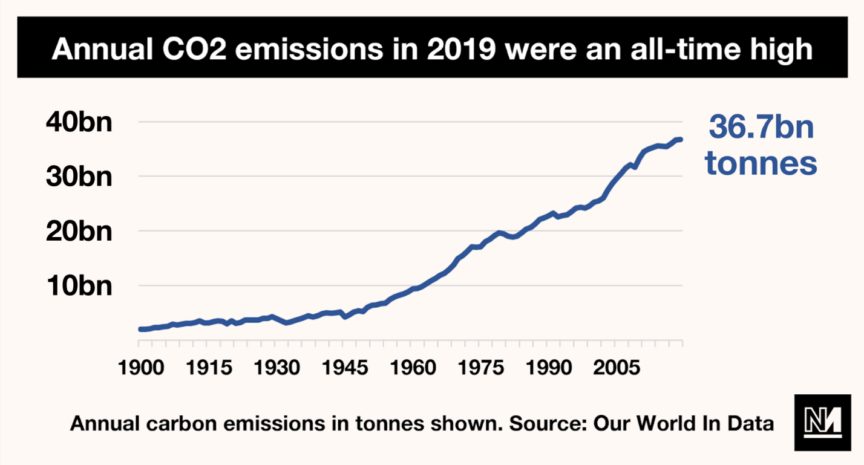

In reality, last weekend’s deal was neither, continuing instead the default of climate politics since the early 90s – namely, the idea that the market will solve the problem. That is all the more remarkable given half of all CO2 emissions since 1751 have been discharged in the last thirty years. We’ve done the most damage to our planet while fully understanding the consequences – and yet a politics of failure has been retained.

For many, the continued gap between rhetoric and action was unbearable. More than once I was told of delegates who had prematurely left out of frustration or disgust. While some remain upbeat about the inclusion of the words ‘fossil fuels’ in the final document, something without precedent, nobody I spoke to described the outcome as “amazing” (unlike ITV’s political editor Robert Peston).

Such an anticlimax is nothing new. As one observer put it, this was conference 26, with every previous iteration – with the exception of Paris in 2016 – a failure in isolation. Has progress been made in the last three decades? Absolutely. Is it sufficient? No. Once you grasp that, the competing claims regarding the merit of these annual jamborees makes far more sense.

1.5C has been buried.

In the immediate aftermath of the pact being signed, the public was told how it keeps the ambition of ‘only’ 1.5C warming alive. While even that level of warming would be disastrous – hundreds of thousands are already on the verge of famine in Madagascar as a result of climate change – anything below 2C has long been the aim.

That is because of a gulf in consequences between 1.5C and 2C of warming. If rising temperatures are limited to the former, there’s a strong chance that the Greenland and west Antarctic ice sheets won’t collapse. At 2C, however, that becomes close to inevitable with sea levels rising up to ten metres as a result – although how quickly is uncertain.

While warming of 1.5C would destroy at least 70% of coral reefs, 2C would mean more than 99% would be lost. The Arctic would face ice-free summers every decade rather than every century, and loss of insect and plant species would be multiple times worse. Most concerning of all, however, would be a likely ‘domino effect’ of permanently rising temperatures from things like thawing permafrost and the loss of carbon sinks such as the Amazon. Two easily becomes three, then four, then five – and so on.

Yet such a tipping point remains speculative, particularly given forecasts for the end of this century presently predict warming of 2.4C, something which humanity could likely adapt to, albeit with great difficulty (before ensuing feedbacks, anyway). According to the Climate Action Tracker the absolute best case scenario, an improbable benchmark given recent history, is 1.8C.

The West’s weasel words.

Earlier this year the International Energy Agency was a little more optimistic, saying that 1.5C was still ‘alive’, but that it would require “no investment in new fossil fuel supply projects, and no further final investment decisions for new unabated coal plants”. While politicians and pundits in the UK have fixated on the coal part, they simultaneously ignore what the IEA says in relation to oil and gas – presumably because the British government plans to grant licences to drill for both domestically. This is why Boris Johnson was keen to emphasise how Cop26 marked a death knell for coal while failing to mention less egregious hydrocarbons. If the UK was serious about keeping to 1.5 degrees then prospective exploration sites, such as the controversial Cambo oil field, would remain untouched.

Another example of such blatant hypocrisy was when European Commission Vice-President, Frans Timmermans, bleated on about grandchildren and deforestation. And yet, in 2019, the EU signed a free trade deal with Mercosur, the South American trade block, guaranteeing increased beef imports already linked to deforestation. Worse still, and during the conference itself, the EU gave €13bn worth of backing to oil and gas projects. In a similar vein Alok Sharma, who choked back tears after China and India pushed back on a late draft regarding coal, is part of a Conservative government which has no issue with Britain drilling for oil at home or the City of London financing fossil fuels abroad.

Finally there was John Kerry, Joe Biden’s Envoy for Climate, who concluded that the deal at Glasgow meant humanity had secured “cleaner air, safer water and a healthier planet”. Fine words, no doubt, but completely at odds with what is happening in the US as the Biden administration prepares to grant the highest number of approvals for new oil and gas sites since George W. Bush. This is indefensible, which is why the impulse to blame China and India was consistently mobilised, despite both being responsible for far lower historic emissions per capita and China making extraordinary progress on renewables. Indeed, while India and China have led the way in reforestation – with all the complications that entails – the US can barely keep up with loss from wildfires.

A path forward from below.

One climate activist who spent days in the ‘blue zone’ told me they were stunned at how the US delegation tried to conspicuously scupper meaningful progress. Yet that is to be expected, and will continue, meaning leadership has to come ‘from below’ – an overused term on the left but one which makes sense when clear objectives can be determined. For British citizens that means a relentless focus on no new oil and gas sites in domestic waters, as well as ending UK financing of drilling abroad. In Britain something similar was achieved with fracking over the last decade with sites blocked across the country as a result of direct action. That unexpected triumph offers a prototype and should now be applied in stopping the Cambo oil field and any new mine for coking coal in Cumbria.

The evidence of the last fortnight is clear: not a single government of a major country is seriously committed to 1.5C warming. Yet in feeling compelled to make at least rhetorical commitments they have created space for movements to shape political common sense for the 2020s and beyond. That is the vacuum that needs to be filled in the run up to Cop27 next year. It also entails making clear that the West are not the climate ‘good guys’, and that parochial, nationalist finger-pointing at the Global South serves nothing but inaction. That is, after all, why the US, EU and UK so frequently do it.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.