With Uber Paying Peanuts, Exploited Drivers Are Cancelling Rides

‘It’s a joke.’

by Polly Smythe

14 December 2021

By the time full-time Uber driver Nader Awaad had logged out of the app after a full day’s work in late October, he’d declined over 100 jobs. It wasn’t because he was unwilling to make long journeys across London, and it definitely wasn’t because he didn’t need the money. Rather, he had rejected every job that wasn’t financially viable.

In recent months, Uber passengers have been complaining of costly fares, long wait times and multiple cancellations. Uber claims the root of these problems is that there aren’t enough drivers to meet high demand. In an attempt to lure drivers to the app, the company has announced it will be increasing its rates for drivers in London by 10% – the first increase of base rates since 2017.

Good to see @Uber buckling under pressure from @UPHD_IWGB strike action but 10% not nearly enough to compensate drivers for years of slashed wages. Uber need to cut the huge 25% commission they charge drivers & up wages! The fight continues! #MakeUberPayhttps://t.co/48KK8oIBMz

— alex marshall (@alexjkmarshall) November 11, 2021

But Awaad, who chairs the United Private Hire Drivers (UPHD) branch of the Independent Workers of Great Britain (IWGB), argues the problems aren’t due to a driver shortage, but the company’s exploitation of its existing drivers. To solve the crisis, he says, we need to ask why drivers are declining jobs in the first place.

A bad business model.

To answer this question, it’s important to understand how the vast majority of jobs Uber offers to drivers have come to have little to no value.

In 2015, Uber began the systematic elimination of the incentives it used to attract drivers onto the app when it first started in 2009, as well as gradually eroding drivers’ pay. Since then, the ride-share giant has slashed the per mile bonus for those driving electric vehicles from 15p to 3p, cut drivers’ commission from customer fares by 5%, and reduced the pay rate to the fixed price of £1.25 per mile (to put that in context, Transport For London’s regulation of black cab fares and tariffs ensures drivers are paid a base rate of £3.20 per mile).

As a result of these cuts, drivers often can’t afford to accept many of the journeys the app assigns to them.

Despite this, Uber has framed the decline in drivers’ pay as a post-pandemic quirk. As an Uber spokesperson told Novara Media:

“During peak times, cancellation rates are happening as drivers are free to pick and choose which trips they accept. This is a temporary issue that is impacting every operator across the country. We see it only occurs in busy places at peak times, as the marketplace rebalances after lockdown.”

However, this drop should be understood as integral to the company’s business model: undercharge users for rides in order to amass a big enough following to dominate the market and establish a monopoly, bringing in vast profits as a result.

Of course, this highly extractive model comes at a great cost. In order to charge less for rides, Uber has increasingly exploited its drivers.

As transport expert Hubert Horan wrote in 2019: “Almost all of Uber’s margin improvement since 2015 [can be] explained by [a] reduction of driver compensation down to minimum wage levels”. If Uber drivers still received their 2015 share of each passenger dollar, he argues, the company’s “negative margins would still be in the triple digits”.

‘Uber wants the crisis to continue.’

Despite the best efforts of Uber’s PR department, it’s clear that the ride-share app’s affordability and convenience is not a result of increased efficiency, but of its systematic exploitation of its workforce.

Like Awaad, many drivers are fighting back by refusing trips. Rema Diallo, an Uber driver and a co-ordinator of UPHD, is one of them. “I get a lot of jobs for £4, £3, £3.75, but I personally never take those […] It doesn’t matter how far it’s going, it’s just not worth it. It’s a self-imposed strike.”

Diallo uses certain criteria to calculate whether his cut of the fare will be worth the time it will take to make the journey. “You’ve got to go half a mile to a mile to find the passenger, which can take 10 to 15 minutes,” he explains. And since drivers aren’t paid for the time it takes to collect a passenger, “it ends up being a waste of time and money. It’s a joke.”

But even in the face of such resistance, Uber is still managing to cash in. When a critical number of drivers decline trips, surge pricing – a fare hike that occurs when rider demand is higher than driver supply – is triggered. Uber benefits from this, as it makes more commission on higher fares. Drivers, on the other hand, reap no such benefits, as drivers’ pay isn’t tied to surges. During peak times, drivers might receive only a few extra pounds, despite customers often paying over double the standard fare – which also makes them less likely to tip their driver. It’s for this reason, Awaad argues, that “Uber wants the crisis to continue”.

Crucially, drivers don’t set the rate of pay and can’t see what passengers are paying for each journey, despite many customers assuming otherwise. Abdi Ahmed, an IWGB member and secretary for UPHD, cites a recent trip from N17 to Gatwick, where the customer told him he was paying £120 due to surge pricing, while Ahmed was only being paid £30 for the journey.

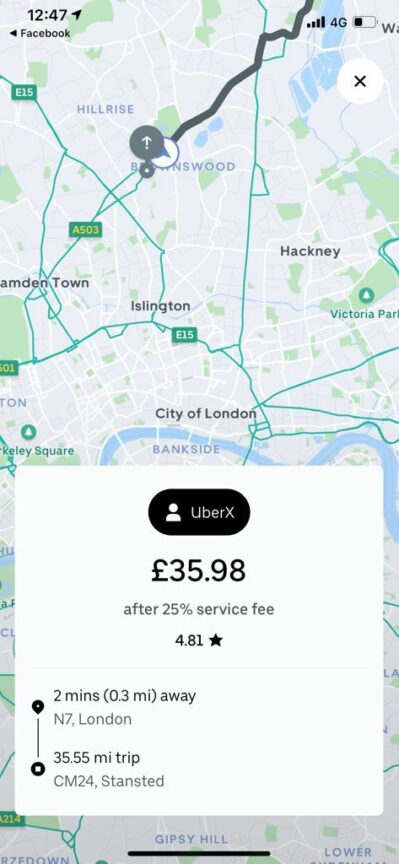

In screenshots shown to Novara Media showing drivers’ calculated pay alongside the length of their journey, trips can amount to little more than £1 per mile: in one case £35.98 for a 35.55-mile trip.

What’s more, despite the supreme court ruling earlier this year that drivers are not self-employed, but workers – and should thus be paid for the time spent waiting for jobs, not just for the time spent on a trip – Uber is still refusing to pay for waiting times.

Hassan Haji, an IWGB member and the member engagement officer for UPHD, explains: “No matter how long you’re stuck in traffic, you’re not going to get paid more”. This is because the app doesn’t factor in variables like rush-hour traffic, speed restrictions or diversions. “In central London, driving a few miles could take me an hour and 20 [minutes],” says Haji. “How much am I getting paid? Peanuts.”

An endless cycle.

Uber has failed to acknowledge these realities and the sky-high rejection rates they have led to, however.

This is in part because the reality of drivers declining journeys is incompatible with the image of the entrepreneurial and flexible worker that Uber has long used to justify the classification of its drivers as self-employed. The narrative the company continues to push is simple: amid spiking customer demand, and a depletion in the supply of drivers due to the pandemic, private hire apps simply can’t keep up with the number of cabs being called.

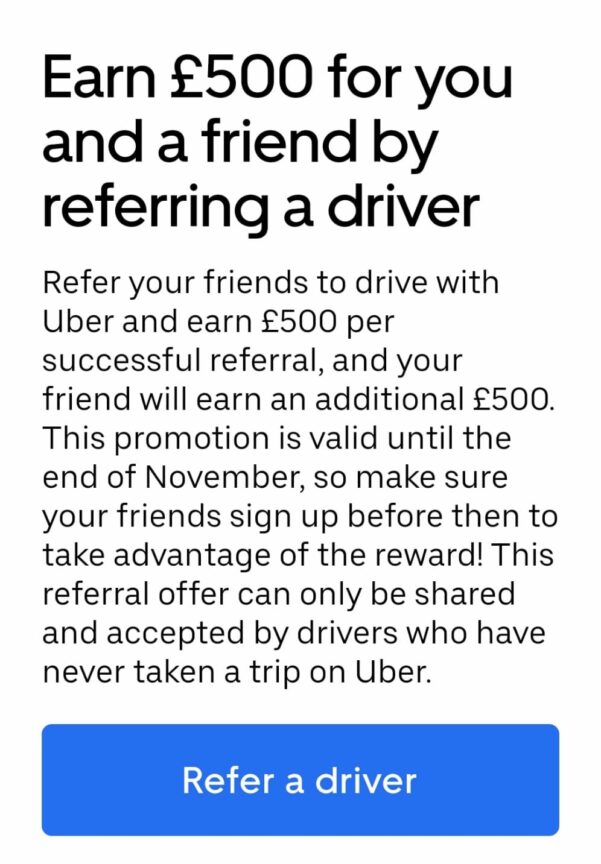

Following this logic, Uber holds that by recruiting new drivers, waiting times will reduce, prices will fall, customers will be happy and the problem will be solved. The company has publicly committed to recruiting 20,000 new drivers by the end of the year, offering drivers “£500 for you and a friend by referring a driver” in November.

But for Ahmed, this bonus was just a cynical attempt to flood the app with a never-ending supply of new drivers, all willing to accept the low-paying jobs other drivers reject in pursuit of this financial reward. “The new drivers will follow the same cycle. Any innocent driver who has just started is still going to struggle, and will eventually talk to the older drivers who are there. It’s not a solution.”

‘Customers take their anger out on you.’

Awaad fears that by accepting the narrative that driver shortages are the problem, it will only make it easier for Uber to avoid questions about the poor working conditions their existing drivers face.

What’s more, with the mainstream press publishing articles with headlines like “Uber drivers get the power to kick customers to the kerb”, it’s hardly surprising drivers are experiencing increased harassment and violence from customers. Ahmed, for example, says he has had passengers send him abusive messages like “Don’t fucking cancel on me, you’re my driver and I pay you”.

The problem is only intensified by the app’s interface, which creates what gig economy researcher Jamie Woodcock describes as “the impression of transparency, with a countdown timer and predicted fare”. Whereas a customer’s experience navigating the app is simple and seemingly transparent, a driver’s is a labyrinth of opaque algorithmic management systems. As Hassan says: “When you pick customers up, they take their anger […] out on you […] [you’re] taking the heat for something that’s not the driver’s fault, but the operators who are using [us] as slaves.”

The fight is far from over.

In the face of Uber’s repeated failure to effectively address the actual cause of the crisis, drivers are fighting back.

On 16 September, the IWGB wrote to Uber setting out its recommendations for how to resolve the problem, including a better rate per mile, a reduction in the cut Uber takes from customer fees and transparency around what the passenger pays for the trip. When Uber failed to respond, drivers took action, holding a one-day strike on 6 October.

#uberstrike @UPHD_IWGB pic.twitter.com/uZdEJjgi2I

— Dr Matt (@MattColeWorks) October 6, 2021

While the company has now increased drivers’ rates (as well as introducing a 15% surcharge for peak times rides to Heathrow, Gatwick, Stansted and Luton) the IWGB argues this does nothing to offset years of driver pay reductions or to cover the increasing costs of operating. If Uber really wanted to solve the problem, it would ensure every fare is profitable for the driver.

“We want all rides to be valued fairly so that we have enough money to pay our costs and live,” says Awaad. “Until app operators deal with the root of the problem, customers are going to be left waiting in the rain.”

Polly Smythe is Novara Media’s labour movement correspondent.