There Is No Sexual Liberation Without Bisexuals

To desire beyond a binary is to know that another world is possible.

by Jacob Engelberg

14 February 2022

In September, Labour MP Rosie Duffield appeared on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, where she was asked about liking a tweet that accused people who identify with the word “queer” of “colonising gay culture”, saying they were “mostly heterosexuals cosplaying as the opposite sex and as gay”.

Rosie Duffield on Radio 4 this morning decrying “men who are married to women who call themselves queer”.

Unclear if she’s misgendering trans lesbians or attacking bisexual men. Illustrative of the interconnectedness of transphobia & bi-phobia. pic.twitter.com/nqc8pX39zh

— Olli Olli Balaam (@0Balaam) September 20, 2021

The claim that trans people are simply playing dress-up is typical of so-called “gender critical” ideology – the same feminist theorist Sara Ahmed more accurately calls “gender conservative” – that promotes biological essentialism and the dismantling of existing anti-discrimination laws for transgender people. The claim that there are heterosexuals pretending to be gay, however, will be less familiar to many but is just as harmful.

In Duffield’s interview, she stated that “there are men, activists, out there who are married to women, who called themselves [queer] and they appropriate gay culture.” For Duffield, it seems, bisexuality is unthinkable.

Although Duffield’s views on gender are widely known, her views on sexuality have gone largely unremarked. This is because disparagement of and even disbelief in bisexuality is often considered unremarkable. Indeed, the unthinkability of bisexuality displayed in Duffield’s words is itself a feature of the British legal system.

“But … you’re bisexual. So what’s the issue?”

In 2016, a bisexual asylum seeker told a Home Office interviewer that his family, who considered his sexuality a sin, was planning to force him to marry a woman. The interviewer was perplexed: “But … you’re bisexual. So what’s the issue?”

Four years previously, the department had denied asylum to Aderonke Apata, a lesbian from Nigeria, for having previously been in a “heterosexual” relationship. Commenting on the case, then home secretary Theresa May’s lawyer Andrew Bird proclaimed: “You can’t be a heterosexual one day and a lesbian the next day.” Research has repeatedly shown that narrow preconceptions around what constitute authentic narratives of LGBTQ+ self-realisation regularly inform asylum decisions, and that applicants conveying complex bisexual narratives are often deemed inauthentic.

It’s perhaps obvious why the right is so resistant to bisexuality: like transness, it calls into question dominant categories of social organisation, those arbitrary social binaries upon which the right relies to divide and rule. Contrary to the popular perception of bisexuality, most bisexual groups today eschew gender binarism, just as we eschew the gay/straight binary; such groups are much likelier to define bisexuality in terms of “attraction towards people of more than one gender” than as attraction to “both” men and women.

The existence of bi and trans people contests the idea that humans are naturally organisable into straight or gay, man or woman. Instead we illuminate the precarious contingencies through which social categories are constructed. It’s unsurprising that the right marginalises us, then; what’s more surprising is that the left does, too.

Leftist biphobia.

The notion that sexuality is a stable phenomenon is observable across much of the political spectrum. In progressive discourses on sexuality, linear coming-out narratives predominate, the revelation of a “true” self who was “born this way”. This framework colludes with sexual essentialism, treating sexuality as an eternal truth unencumbered by history or culture. It also imagines a universal coming-out journey from secrecy to disclosure, another binary that assumes an unchanging sexuality. But on a more basic level, it simply doesn’t reflect the realities of many queer people.

people who used the bisexual label and later realize they’re lesbians and people who used the lesbian label and then realized they’re actually bisexual – there is nothing wrong with you. no journey to finding ones sexuality is linear. you are okay

— medusa’s gf (@isapphic) July 19, 2019

Bisexuals often don’t sit comfortably with the idea of coming out. If we do come out – and we disproportionally don’t – our journeys are usually not linear but repeatedly renegotiated. A bisexual coming-out does not necessarily repudiate an “inauthentic” past, and our sexualities cannot be read straightforwardly by the gender of our partners. We are not born either “way”; for many, our sexualities have changed over time. Bisexuality troubles dominant ideas around the gay, cis man imagined to be the typical LGBTQ+ subject. This is a trouble the left should leverage, not avoid.

Since the 1970s, bisexual activists have identified the political stakes in contesting the gay-straight binary. In the first Politics of Bisexuality conference held in London in 1984, a draft “bisexual manifesto” challenged both the gender and the sexuality binaries in ways that resonate today: “We believe that the existing categorization of men and women, homosexuals and heterosexuals is misleading.”

“The prevailing heterosexist ideas about sexuality,” the authors continued, “have created restrictive and damaging categories into which the diversity of human sexuality does not fit. We believe that bisexuality challenges the order and origins of these categories.”

This early articulation of bisexual politics rejected not only the sexual conservatism of the right, but also the inchoate strategies in the gay left which sought to normalise homosexuality. From the 1970s onwards in the UK and US, dominant liberal strands of gay politics tactically promoted the notion that homosexuality was natural, stable and immutable as a means of making legislative gains.

Homonormativity.

This strand of gay politics sought to render queerness palatable, unthreatening, and assimilable by presenting an uncomplicated, normative, and depoliticised image of gay subjecthood. As legal scholar Kenji Yoshino observes, gay rights advocacy has regularly been mobilised through the erasure of bisexuality, whose potential for mutability and nonlinearity resists incorporation within liberal modes of sexual subjecthood.

In a process David Eng calls queer liberalism and Lisa Duggan the new homonormativity, recent decades have seen the folding in of certain gay people as citizen-subjects into institutions from which they were once excluded, such as marriage, homeownership, adoption and the military.

This has an international dimension too. Under what Jasbir Puar terms homonationalism, “gay rights” have been instrumentalised by governments to naturalise Western exceptionalism and imperialism, as well as by international financial institutions to circumvent their responsibilities around global inequalities. This alone should tell us enough about the suitability of liberal LG(bt+) politics – the typical, capitalised formulation belies the movement’s parenthesising of bisexuality and transness – to the leftist project.

The construction of the paradigmatic “the gay rights holder” necessarily repudiates those queers who do not meet its strictures. Asylum seekers for one are regularly deemed undeserving of sexual minority subjecthood. Between 2015 and 2019, almost 7 in 10 of those seeking asylum in the UK on the basis of their sexuality had their application initially refused.

In 2013, a judge ruled against Jamaican asylum seeker Orashia Edwards, saying that while she accepted he’d had “experimental sexual encounters” with men, she did not “find it reasonably likely that he is bi-sexual” [sic], a chilling example of the state’s ability to determine the legitimacy of one’s sexuality. Here, a radical bisexual politics must respond that it is not queer asylum seekers’ complex histories that are bogus, but the very notion of sexual authenticity itself.

Yet this sociopolitical preclusion of bisexuality from notions of legitimate sexual subjecthood cannot be separated from our social realities.

The bisexual struggle is real.

Bisexual people in Britain experience disproportionately more intimate partner violence, unwanted sexual contact, depression, suicidality and self-injury than both gay and straight people, as well as more poverty, low-income employment and unemployment. It’s here that bisexual politics has a natural alliance with trans politics, as it did during the 1990s.

Contemporary trans politics focuses on issues like healthcare, homelessness, workplace discrimination and sexual violence – material inequities that affect our social groups in an overlapping fashion. The fact that, according to the most recent government figures from 2017, the majority of trans people in the UK identify as bi- or pansexual (45.7%) should reinforce those connections.

A radical leftist bi-trans alliance would work to disrupt the normalising binaries that undergird systems of social oppression, all the while centring the social realities engendered and maintained by these same systems. As our political representatives declare themselves “LGBTQ+ friendly”, together we ask: friendly to whom?

In Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution, Shiri Eisner writes that a radical bisexual movement “would embrace the inauthenticity, impurity, and hybridity that comes along with bisexuality”. Here Eisner lays claim to those qualities that have so regularly been used to exclude bisexuality from serious political discussion. That we are inauthentic, impure, or hybrid can serve not as pejoratives, but as a reminder of the radical threat bisexuality poses to staid sexual norms. It’s not just bisexuals who have something to gain from such sexual politics – we all do.

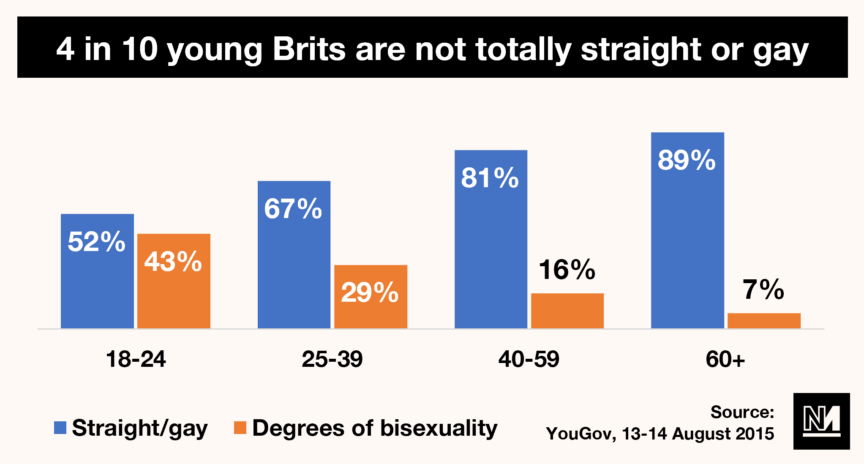

According to the most recent ONS figures, 4.1% of UK 16-to-24-year-olds identify as bisexual, significantly more than those identifying as lesbian or gay and the highest proportion to identify as bisexual in recent years. The future of the British left requires not simply embracing bisexuality but taking inspiration from it. Bisexuality’s interstitiality models a politics of solidarity between and beyond difference. Its resistance to proscribed sexual categories challenges us to imagine leftist utopias hitherto unrealised. To desire bisexually in a society structured by a gay/straight binary is to know that another world is possible.

UK-based bisexual initiatives include: Bi Community News, The Bi History Project, the Bi Survivors Network, Biscuit, The Bisexual Index, The Bisexual Research Group, and Bi Pride UK.

Jacob Engelberg is a PhD student and teaching assistant in film studies at King’s College London.