The Wages for Housework Campaign Is As Relevant As Ever

'It's an invitation to do politics again.'

by Sophie K Rosa

21 March 2022

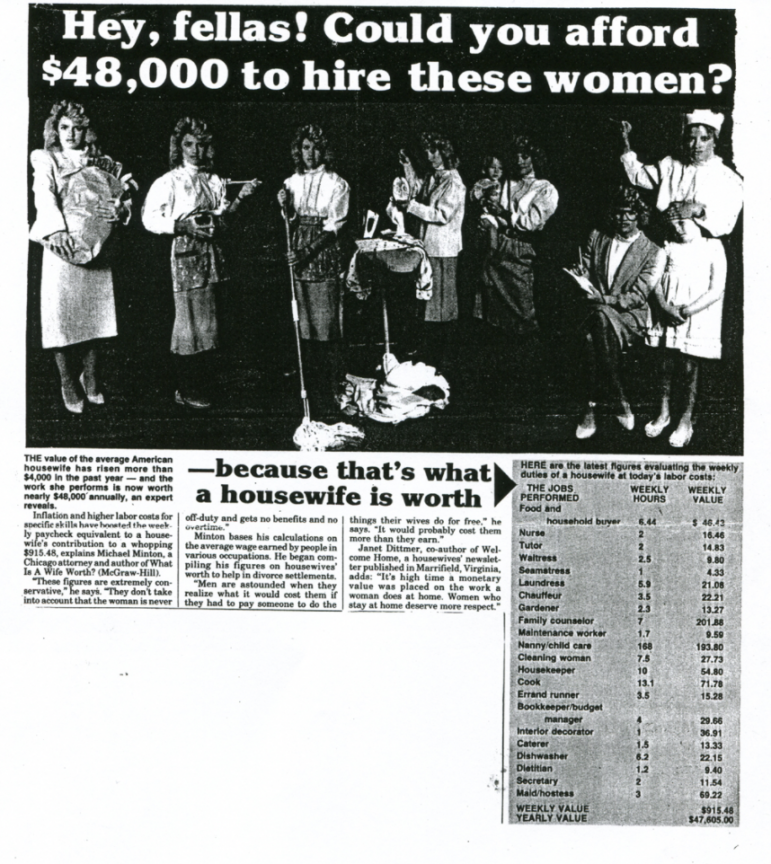

“Hey, fellas! Could you afford $48,000 to hire these women? Because that’s what a housewife is worth.” So reads the headline of a 1970s edition of US newspaper the National Enquirer. The calculation quoted in the article takes into account the numerous jobs housewives typically fulfil – including childcarer, cleaner, chef, dishwasher, nurse and family counsellor.

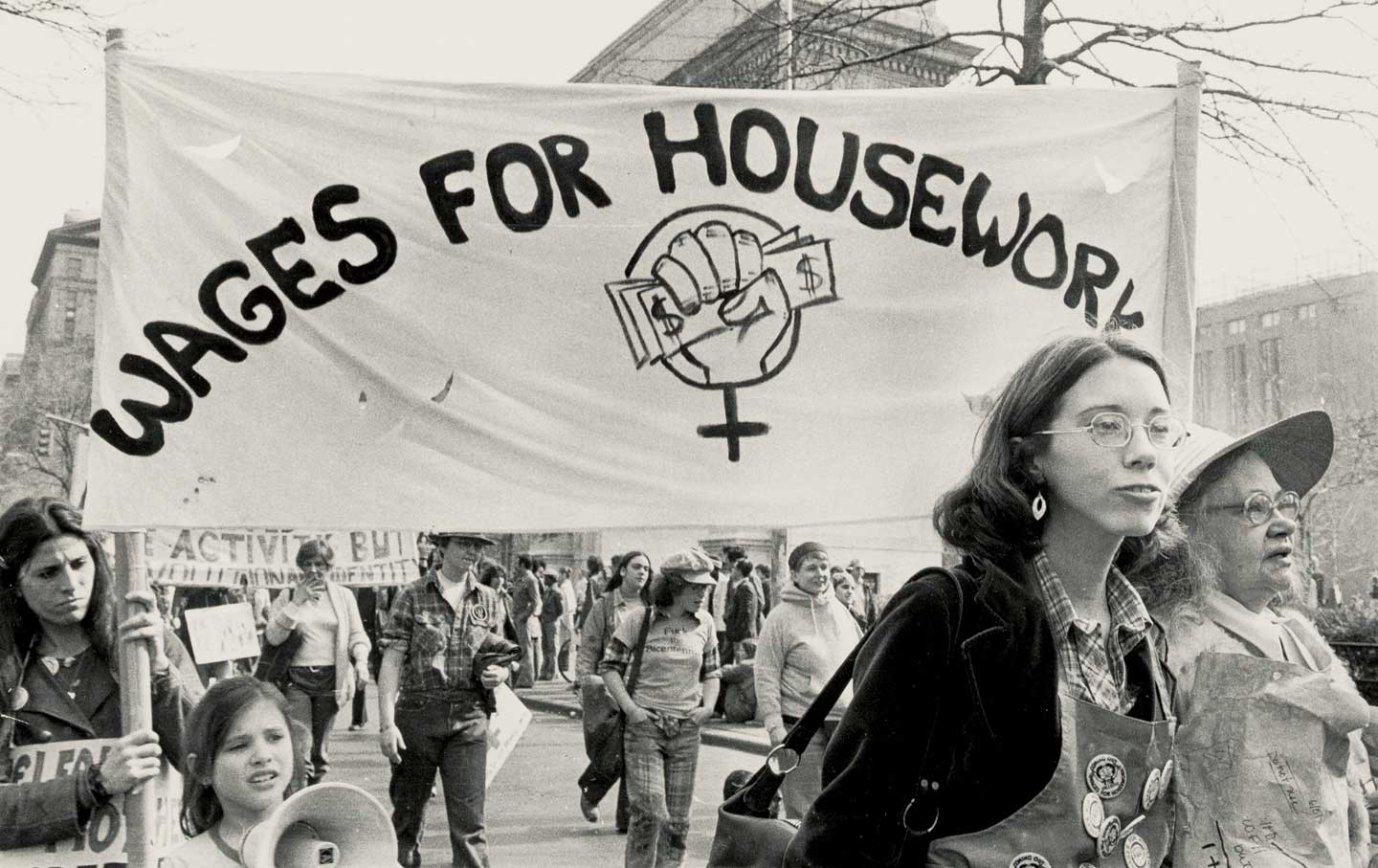

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the ‘wages for housework’ (WfH) campaign, an internationalist, anti-capitalist, feminist movement that rejects an economic order in which women’s essential domestic work goes unrecognised, undervalued, unremunerated or underpaid.

The WfH campaign brought a powerful new perspective to the feminist movement, both in Britain and around the world – a perspective that its original organisers, reflecting on their experiences with Novara Media, argue is just as urgent as ever.

‘We had to invent a totally different style of politics.’

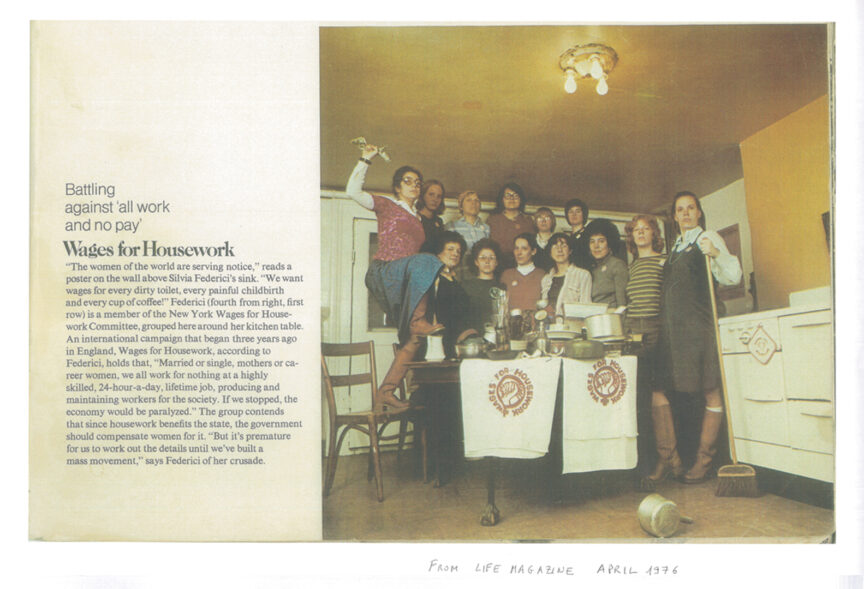

The WfH campaign was launched by the International Feminist Collective at the 1972 International Feminist Conference in Padova, Italy. Within two years, it was holding its own international conference in Brooklyn, New York, with WfH groups organising in the US, Canada, the UK, Italy and beyond. “The headquarters of these groups were […] creative outlets where women learnt to do the most diverse things,” explains WfH organiser Mariarosa Dalla Costa.

The campaign broke with old ways of ‘doing politics’, another WfH organiser, Leopoldina Fortunati, recalls fondly: “The politics made by men was essentially boring […] we had to invent a totally different style […] in which there was a lot of joy – the joy to stay together with the other women, to overcome the isolation of the home.”

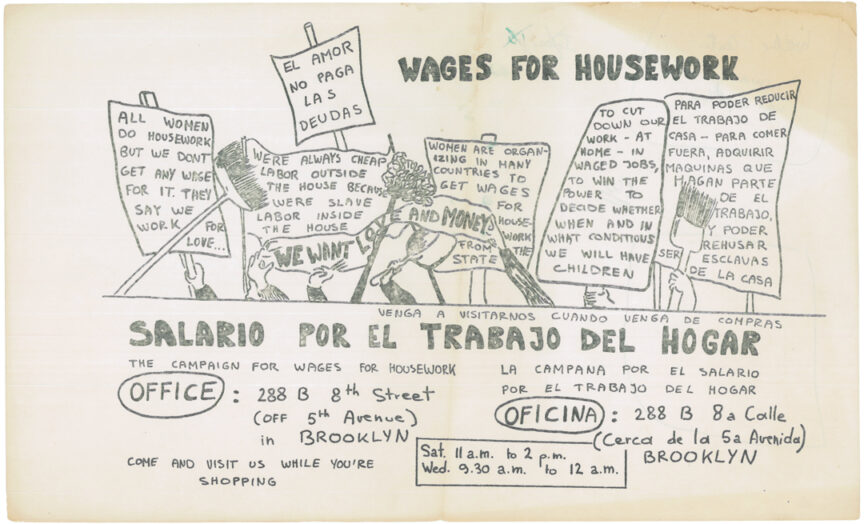

Whilst WfH incorporated diverse perspectives and struggles, its uniting demand was clear: that caring labour, mostly done by women, is not biological destiny or ‘love’, but – under capitalism – work that should receive a wage.

This claim was, and still is, radical. Women’s unpaid labour is not accounted for in a country’s GDP, and is not respected as ‘real work’. Indeed, it is erased, says WfH organiser Selma James.

The ‘housework’ the campaign referred to acted as shorthand for all feminised labour, in and outside of the home. This socially reproductive and affective labour – the work that births new workers and keeps people alive and well enough to, in turn, work (i.e. fucking, feeding and not hurting men’s feelings) – went unacknowledged by both the patriarchal left and the labour movement. WfH activists set out to change this.

All women are workers.

The WfH campaign insisted that all women were workers who kept the cogs of capitalism turning, and that all households were workplaces. The demand for a wage was, in part, symbolic: what mattered was that women’s gruelling and thankless work was recognised, such that its conditions could be fought against – and, indeed, ultimately refused. “The question of housework,” says Dalla Costa, was “a question that determined conditions for all women.”

“We are teachers and nurses and secretaries and prostitutes and actresses and childcare workers and hostesses and waitresses and cooks and cleaning ladies and workers of every variety,” read one WfH pamphlet entitled ‘NOTICE TO ALL GOVERNMENTS’. “We have sweated while you have grown rich. Now we want back the wealth we have produced.”

The campaign provided a platform for militant feminist struggle against women’s oppression. It was a political perspective committed to – as WfH organiser Silvia Federici wrote in her essay ‘Wages Against Housework’ in 1975 – “demystifying and subverting the role to which women have been confined in capitalist society”. This perspective allowed for women’s everyday lives to be reframed as the location of political struggle: “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work. They call it frigidity. We call it absenteeism. Every miscarriage is a work accident.”

A fight on many fronts.

Recognising women’s labour under capitalist patriarchy as work had far-ranging implications. As such, the campaign fought on many fronts: campaigning for women’s shelters and sex worker rights, lesbian liberation and free childcare, reproductive autonomy and sexual freedom, and affordable housing and public transport provision.

As Dalla Costa puts it: “The demand for wages for housework, first and foremost, offered a perspective that allowed for a new way of initiating or formulating a whole host of struggles taking place in our neighbourhoods, in our homes, but also in hospitals, factories [and] in the service sector. These struggles represented the social articulation of the demand for wages for housework.”

Looking at reproductive autonomy from the WfH perspective, for example, allowed liberation in the domestic sphere to become part of the anti-capitalist struggle. Articulating this, one pamphlet read: “When they need more workers, we women are forbidden any form of contraception […] When the workers we produce are not disciplined enough, or when we claim some money for the cost of raising them – that is, when WE are not disciplined enough – they sterilise us.”

Reconceiving the home as a workplace also meant domestic violence could be understood in the context of capitalism’s exploitation of both men and women. In ‘Wages Against Housework’, Federici linked men’s exploitation at work to their exploitation of and violence against women inside the home, arguing that massifying women’s well-honed individual modes of resistance into class struggle was crucial for the feminist movement:

“You beat your wife and vent your rage against her when you are frustrated or overtired by your work or when you are defeated in a struggle (to go into a factory is itself a defeat). The more the man serves and is bossed around, the more he bosses around […] (Women have always found ways of fighting back, or getting back at them, but always in an isolated and privatised way. The problem, then, becomes how to bring this struggle out of the kitchen and bedroom and into the streets.)”

Making the invisible visible.

The WfH perspective flew in the face of other strands of feminism that insisted women’s liberation rested upon their entering the job market, leaving ‘housework’ to low-paid domestic workers, often racialised women. Rather than ‘solving’ patriarchy by slotting more women into higher paid roles outside of the home – inevitably leaving most women to continue unpaid or low-wage work – the campaign insisted that the work that women were already doing must be recognised, respected and recompensed. The demand acted as a mechanism by which to render feminised work visible so that it could be effectively struggled against – in order to, ultimately, build a feminist future in which such caring labour would be collectivised.

In general, on the radical left, “the question of women was completely ignored”, says Fortunati. The feminist movement had identified that recognising domestic labour as work “was fundamental to beginning a revolution [which centred the] political perspective of women”. Dalla Costa, too, was drawn to WfH after recognising that feminism was largely absent from the militant political groups she was organising with: “I realised that while I was fighting with everything I had for various subjects, one among these subjects was missing: women.”

WfH’s feminism challenged a capitalist chauvinism that, despite being “really dependent on [women’s] work […] denied it was work”, says James. In their essay ‘Counter-Planning from the Kitchen: Wages for Housework – A Perspective on Capital and the Left’, Federici and Nicole Cox argue: “Since the left has accepted the wage as the dividing line between work and non-work, production and parasitism, potential power and powerlessness, the immense amount of unwaged labor that women perform for capital in the home has escaped their analysis and strategy.” This perspective, they say, “is functional to our enslavement to the home, which, in the absence of a wage, has always appeared as an act of love”.

An international, intersectional campaign.

In one way or another, the WfH cause was relevant to women everywhere, and the internationalism of the campaign was a central source of its power, says James. Whilst the women’s movement, broadly speaking, entailed “a kind of provincialism which was unavoidable [because women were isolated]”, the campaign sought to facilitate organising among women across the world. “We spent a lot of our money on international calling; we had pennies but we put them into phone calls,” she says. “There was not going to be any campaign that was anti-racist unless it was international.” For organisers in the Global North, she continues, it was crucial to recognise “the enormous work that [women were doing] in the Global South”, given that they were working days of “16, 17 hours”.

In today’s vocabulary, the WfH campaign might be understood as aspiring to practise ‘intersectionality’. Whilst recognising shared oppression, organisers tended to place importance on women’s multiple identities, and how those identities differentiated their struggles. “Every woman who came into the campaign brought her own story and that’s how we educated ourselves,” says James.

In this context, autonomous groups began forming around the central campaign. International Black Women for Wages for Housework, which was founded in 1975, described itself in a pamphlet as “a network of Black/Third World women claiming reparations for all our unwaged work including slavery, imperialism and neo-colonialism”. The group wrote that it was “campaigning on welfare, immigration controls, police illegality, health, rape and domestic violence, nuclear power/weapons and ecological devastation integrates Black/Third World, women’s and green issues”.

Meanwhile, Wages Due Lesbians, which was founded in the same year, highlighted and fought against the specific oppressions lesbians faced, which were not always accounted for in some of the ways WfH was framed. The group, for example, expressed shared struggles with sex workers, writing:

“As lesbian women we, like prostitute women, refuse to accept that it is women’s ‘nature’ to sleep with men and to sleep with them ‘for love’ — i.e . for free. And like prostitute women we face continual harassment by police, employers, schools, individual men, and all those in authority for the crime of shaping our sexual life according to our own needs, of taking something for ourselves […] Women, lesbian or ‘straight’, prostitute or not, are everywhere houseworkers, the servants of the world.”

Sex workers, in turn, set up their own autonomous groups – for example, the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP), which was founded by two immigrant sex workers in 1975 and still organises under this name today. The ECP campaigned for the “abolition of the prostitution laws; for human, legal and civil rights for prostitute women; and for higher benefits, student grants, wages and other resources so that no woman is forced by poverty into sex with anyone”. In 1982, ECP activists occupied a church in King’s Cross, London, to protest police racism and violence.

In 1975 the ECP started as an autonomous organisation within the Wages for Housework Campaign. At the time the WFHC was one of the few women’s organisations that was ready to work with sex workers and help us defend our rights. #ECParchive https://t.co/si24WP4R5n pic.twitter.com/D0rwV1U6kZ

— English Collective of Prostitutes ♀️ 🏳️⚧️ (@ProstitutesColl) March 17, 2022

Other autonomous groups included Women against Rape, which campaigned for the criminalisation of rape in marriage, and WinVisible, a group of “women with visible and invisible disabilities campaigning for economic independence, autonomy and mobility, housing and other resources for independent living, and against cuts in welfare and services racism, rape and military-industrial pollution”.

These groups intended to address the differences between women’s experiences – and, in doing so, attend to the complicated power dynamics in the wider campaign.

That said, maintaining a united front was also important. To that end, groups identified the places where their struggles overlapped along the framework of WfH in order to build solidarity. In its foundational manifesto ‘Fucking Is Work’, Wages Due Lesbians explained the shared struggle of housewives and lesbians:

“Wages for Housework recognises that doing cleaning, raising children, taking care of men, is not women’s biological destiny. Lesbianism recognises that heterosexual love and marriage is not women’s biological destiny. Both are definitions of women’s roles by the state and for the advantage of the state.”

This spirit of solidarity informed the campaign’s key tenets, says James: “if you want to fight, we will fight alongside you”, “always take the struggle of others into consideration” and “we do not scab on each other”.

Given its ambitions, it’s hardly surprising that the political organising of WfH was “intense”, says Fortunati. “There were so many things to do to enlarge and strengthen the movement.” This included co-writing, event planning, demonstrations, public assemblies, leafleting and postering. “We were involved every day, and we worked very intensively for a decade.”

One thing that made WfH special, says Dalla Costa, is the way that the campaign combined “theoretical training with a serious commitment to political militancy and action”. Whilst analysis was vital, the campaign steered clear of “academic debate” to instead focus on “mobilising to instigate a social transformation that would allow women to redefine themselves and their condition”.

‘Women’s labour is worth more than capitalism could ever pay.’

While the WfH campaign did not ultimately win a concrete wage for women’s unpaid labour, that was never really the point, says feminist researcher, organiser and mother Claire English. She argues that the campaign was successful in many ways, particularly in terms of reminding people that “women’s labour is worth more than capitalism could ever pay”. WfH was, she says, “a wrench to open up our eyes to how completely unsustainable society is when it relies on the endless capacity of women”. The fact that it is most likely “impossible under neoliberal capitalism” to pay women for their work in the home “really just lays bare why we’re making the demand in the first place”.

Whilst women’s unwaged work still goes undervalued and unrecognised to this day, there has been more formal recognition of its existence since WfH. The United Nations argued for the importance of women’s unwaged labour in national economic analyses in 1985, writing: “The remunerated and, in particular, the unremunerated contributions of women to all aspects and sectors of development should be recognised, and appropriate efforts should be made to measure and reflect these contributions in national accounts and economic statistics and in the gross national product.”

More broadly – and arguably more importantly – WfH helped instigate a shift in feminist consciousness. Thanks to the campaign, women’s burdens and agonies are no longer merely a private matter: now, they are a part of the political terrain. For many women, this was a critical shift in perspective, opening up possibilities for collective resistance and transformation.

Overcoming fragmentation.

Since the 1970s, the global feminist movement has had many victories in areas that WfH was fighting, including in reproductive autonomy. The campaign also “paved the way for conversations around things like UBI because it’s about making a payment that people can live on without tracking their every move in exchange for it”, says English.

But whilst WfH laid out new terms for feminism, there is much work to be done to claw back its radical remit. Today’s liberal feminism – in which the existence of so-called girlboss CEOs is lauded as liberation – is worlds away from the radical anti-capitalist, feminist politics of WfH. This has been true since the 1980s, says Dalla Costa, when “feminism completely expunged material conditions from its vocabulary”.

With that in mind, it is vital that the feminist movement today finds ways to overcome this fragmentation. It could be helpful to find places where the two ideologies overlap, says English, who highlights the fact that WfH has been considered “the very first recognition of emotional labour in the domestic sphere”. In this way, parallels can be drawn with liberal feminism, she argues, which is interested in the ways in which women’s disproportionate ’emotional labour’ often goes unrecognised.

The crux, then, says English, is “convincing liberal feminism that the emotional load needs to be collectivised, and that we need to organise against it”, as opposed to pursuing only individualised solutions via, for example, marital disputes and ‘outsourcing’ domestic work to poorer, racialised women.

‘An invitation to do politics again.’

50 years on from its inception, the WfH campaign serves as an essential reminder that any feminism worth its name must be for all women, and centred on resisting the roots of oppression – which lie in patriarchal capitalism – rather than merely tinkering around the edges. The 1970s, according to Dalla Costa, was an era characterised by a “social ferment [… ] in which everything was up for grabs from the perspective of building a better world”. While it might be harder to grasp that optimism today, “at a time marked by the immiseration of the female condition, in the context of relentless precarity, low wages and the winds of war”, it is all the more urgent and vital that we try.

And what’s more, there is no need to start from scratch. The WfH campaign – and the radical feminist tradition it is a part of – lives on in various forms. Many of the autonomous groups still operate, sometimes under different names; Wages Due Lesbians, for instance, is now QueerStrike. Meanwhile, in the UK, the Global Women’s Strike and the Women’s Strike Assembly are fighting on the same terrain, with a focus on the strike as a mode of resistance.

English has organised with the Women’s Strike Assembly, on a series of ‘My Mum is on Strike’ events, “premised on viewing mothering work as a form of labour that has to be denaturalised, recognised and collectivised”. The strike, as a tactic, she explains – like the demand for wages – is a mechanism that, in its disruption and shock factor, calls “people to look at just how impossible the situation for women is when so much of the basic functioning of society rests on how much can be extracted from our exhausted bodies and minds”.

The original WfH organisers who spoke to Novara Media are united in the belief that today’s feminist movement must look to the campaign for revolutionary inspiration. On its 50th anniversary, WfH “is an invitation to do politics again”, says Fortunati. This means centring what the campaign was really about, says James; creating “a world that begins with caring and not with profiteering”. In striving for this, we must, as Federici wrote, “call work what is work so that eventually we might rediscover what is love”.

Sophie K Rosa is a freelance journalist and the author of Radical Intimacy.