Student Loans Are Now Even More of a Scam

Lower middle income earners will be hit hardest by government reforms.

by Aaron Bastani

26 April 2022

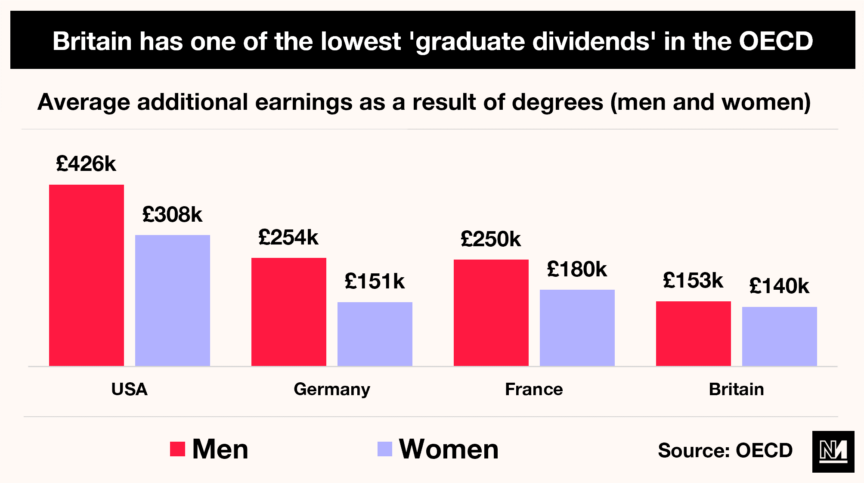

According to the OECD, England has the most expensive publicly-funded university system in the world. Despite this, the ‘graduate dividend’ for English students – the additional lifetime earnings they can expect – is relatively small. A degree in the UK leads to extra earnings of £153k for men and £140k for women – less than the international average of £209k and below the likes of France, Germany and Ireland (where tuition is free). While college debt in the US is far higher, graduates can expect an equally massive shift in projected earnings: a typical male graduate in the US will earn £426k more over his career, while a woman will earn an extra £308k.

While hardly an advert for English universities, this nevertheless suggests that studying for a degree in England (fees, grants and student finance differs across the home nations) is worthwhile. On graduation, the average English student now has a student debt of around £45k. While interest means that quickly rises, fewer than 20% of graduates are forecast to fully repay their loans. If you fall into this category, you will have earned significantly more than if you chose not to enter higher education at all.

Now, however, just as in 2010, the government is reforming the student loan system. What do prospective changes from 2023 mean, and are they likely to undermine the economic value of going to university?

Making sense of UK student finance.

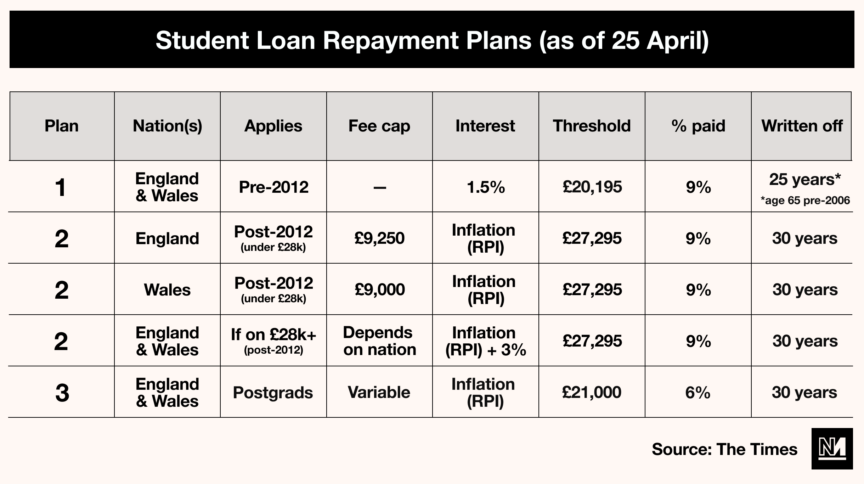

As with tuition fees, the terms of one’s student loan – from the interest rate to the repayments threshold – depends on when and where you studied. Scottish students don’t pay tuition fees (English, Welsh and Northern Irish students in Scotland do) under an arrangement called ‘Plan 4’. Welsh students, meanwhile, have the same financing as those in England (Plan 2), although they receive grants worth at least £1k a year. Students in Northern Ireland have the same loan options as students in England and Wales before 2012 (Plan 1). English and Welsh graduates who studied between 1998 and 2012 are also on Plan 1.

Compared to what came after 2012, Plan 1 is relatively generous. Alongside far lower tuition fees, the interest rate on Plan 1 loans is more favourable (mine presently stands at 1.5%.) Repayments kick in at £20,195, with 9% on earnings above that taken back. If you began your degree before 2006, your Plan 1 Loan will be written off when you turn 65. If you started after that date, and before 2012, it will be written off after 25 years.

For those on ‘Plan 2’ loans – who studied over the last decade – the interest rate is higher. If you earn less than £27,295, it is linked to RPI (a measure for inflation which is presently 6.8%), while if you earn more it is RPI plus 3%. When inflation is low, that might not seem like a major shift, but when it ticks up – as it has this year – then interest rates start to resemble a credit card. Indeed, interest rates on ’Plan 2’ student loans are expected to reach 12% in 2022. As well as this, the threshold at which graduates start to repay their loans is higher – £27,295 – while the debt is written off after 30 years.

This post-2012 system is so badly designed that modelling by the IFS suggests just 17% of graduates will repay their loan in full. While significant non-repayment was anticipated, this is far beyond what was modelled: when preparing the reforms in 2010, the government claimed the taxpayer would pay for around 30% of student debt. In 2017, the IFS found that figure was closer to 45%. Today, it is likely higher still.

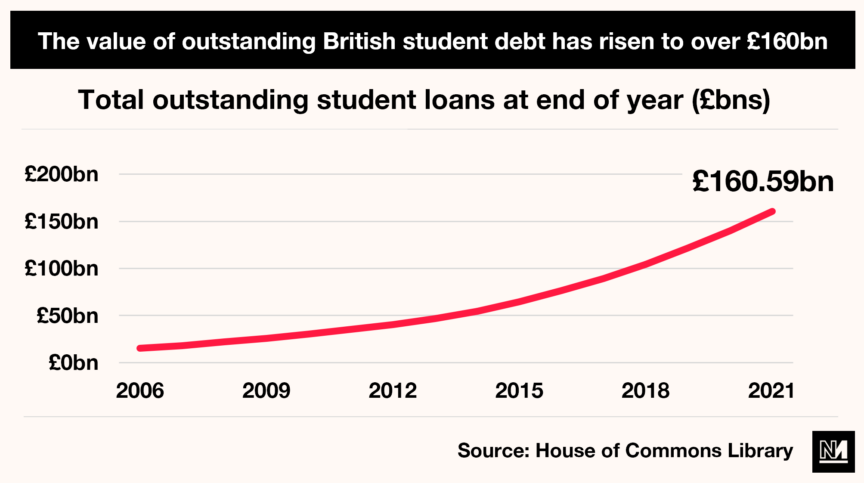

This is a problem for the Treasury. Every year £20bn of student loans are awarded, meaning outstanding student debt has surged from £35bn in 2010 to £160bn last year. By the middle of this century, that figure is expected to rise to £560bn, at which point a difference of 20% in the government’s share of the overall liability is an extraordinary, unexpected cost. That’s why the proposed changes are a matter of urgency for the government: under the new arrangements, it is hoped that 70% of graduates will repay their loan in full rather than 17% (though some estimates put this as high as 25%).

So what do these proposals look like? Graduates will repay their loans sooner (the threshold falls to £25k) and for longer (the maximum repayment period increases from 30 to 40 years). As something of a palliative, the interest rate is slightly lower. This is expected to create £2.3bn of savings for the Treasury for each university cohort – money coming directly from middle and low income graduates as they repay their student debt into their sixties.

As well as confirming the failure of earlier reforms, the distributional effects of these proposals is spectacularly regressive. The winners are high earning graduates who, according to the IFS, save £24k as a result of the lower interest rate. For the very lowest earning graduates there’s little difference, as they won’t repay anything as long as their earnings stay below £25k. While these graduates will have a longer repayment period, the lower interest rate makes up for that.

The group that does lose out, however, is also the largest: those on ‘lower middle’ earnings. Analysis by the investment firm AJ Bell found that a graduate on a starting salary of £24k on graduation, with a 2% increase each year until they retire, would repay £47k under the present system but £101k under the new proposals, meaning that much touted ‘graduate dividend’ largely disappears. This is the same demographic that will struggle to get on the housing ladder, start a family or generate sufficient savings for retirement. If you wanted a policy designed to hammer the ‘squeezed middle’ of tomorrow, it would look like this. If the graduate is a woman hoping to have children it’s even worse, because while men (on average) are expected to pay less under the new system (as a result of the savings made by high income earners) women will pay more. Why? Because they take longer out of the labour market to have children – meaning the longer repayment period hits them the most. As birth rates fall (much to the puzzlement of the conservative media), the government’s proposals make it even harder for young women to start families. Worse still, repaying their student loans into their sixties will mean these graduates can allocate less for retirement. While a crisis of elderly care is set to hit OECD countries over the next decade, evidence suggests it will only get worse for millennials, Gen Z and those thereafter.

Tax the poor to subsidise the rich.

Why are the Tories doing this? It certainly isn’t to fund higher education: despite inflation hitting 6.8%, tuition fees have (rightly) been frozen. While this is good for students, it’s bad news for universities, which aren’t seeing additional government funding to make up the shortfall. Alongside this is a move to cut funding for creative and arts subjects by 50% from September. Both changes reflect a continued squeeze on higher education funding – the norm since 2010.

Rather than creating better universities, the government’s intention is that fewer people will enter higher education – even if that means those choosing to study nursing, adult care and teaching lose money for completing a degree (for many pursuing such subjects, the graduate dividend seemingly disappears under the new arrangements.)

More than anything, the government’s proposals show what a spectacular mess the coalitions reforms were. Despite burdening generations of citizens with higher debt, and taking a sledgehammer to Britain’s reputation for research excellence, the taxpayer is still on the hook for tens of billions more than David Willetts, David Cameron and Nick Clegg foresaw. Once again, those trying to make something of themselves – and be of service to their communities – are left picking up the bill.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.