Britain Has Ditched Masks and Disabled People Along With Them

Is it really that hard to wear one?

by Sophie Buck

9 May 2022

When mask mandates aboard US aeroplanes were dropped on 19 April, mid-flight reaction videos flooded the internet. One from NPR showed passengers tearing off their masks and celebrating, while their masked neighbours watched.

View this post on Instagram

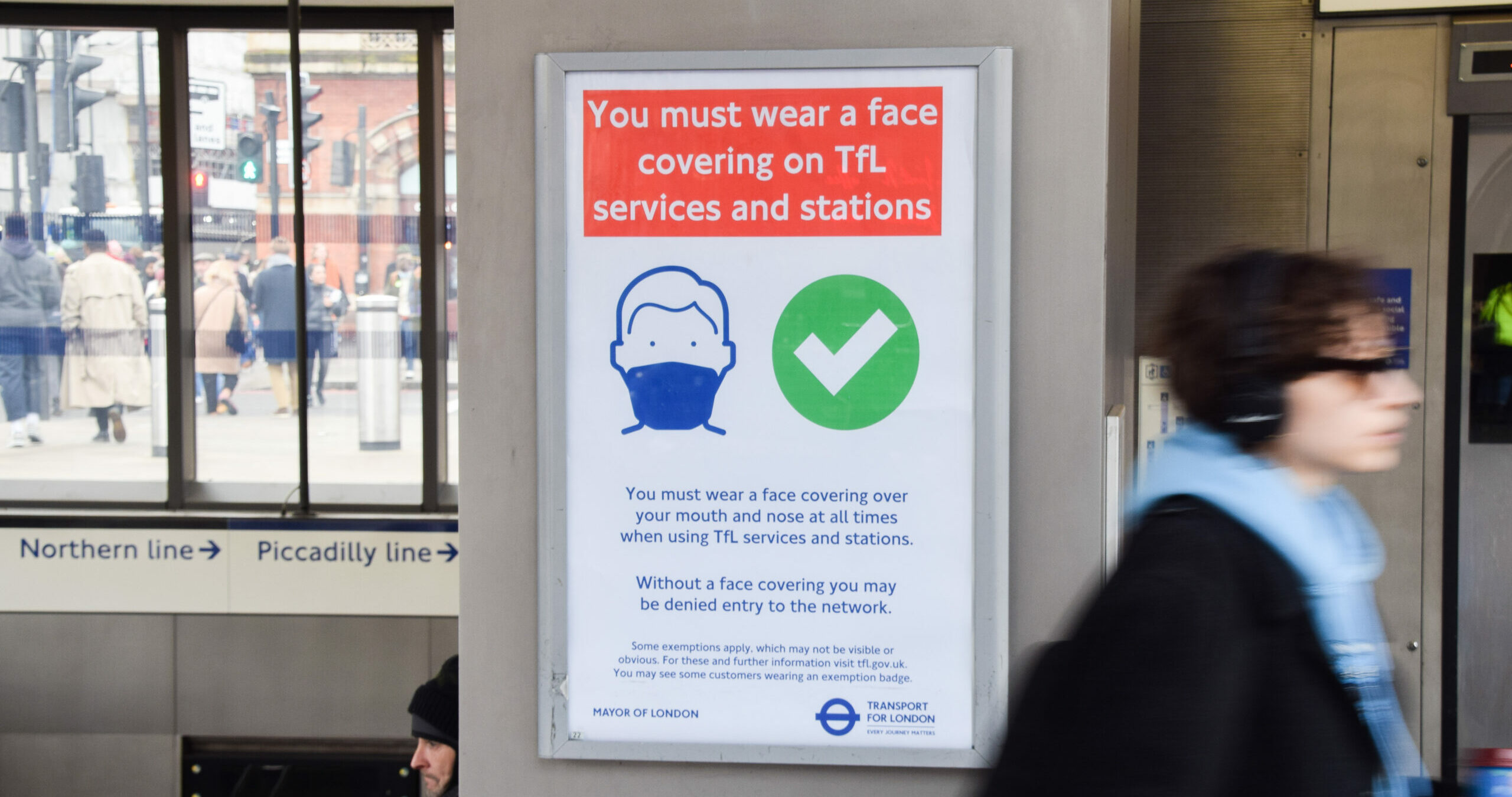

The removal of mask mandates has been similarly welcomed in the UK. According to data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), April saw the lowest mask-wearing rates this year. Over 85% of respondents had seen only “some people”, “hardly anyone” or “no one” wearing a mask on public transport or in shops during the week prior; only 50% – 30% for those aged 16-29 – wore masks regularly in these places themselves, despite it still being advised. This response is in-keeping with the UK’s relative resistance to masking throughout the pandemic: a July 2020 article in the American outlet Bloomberg noted that, despite having the highest death toll in Europe, only 38% of Britons wore a mask – a statistic they described as “astounding”.

While most of the UK is acting as if the pandemic were over, this is far from the case. According to ONS data, around one in 35 people in the UK have Covid – likely an underestimate due to greatly reduced testing since Covid tests are no longer free, and a quarter of infections are now asymptomatic. Each day, hundreds of people in the UK still die from the virus, three in five of whom are disabled (despite many still shielding). 1.8 million people have long Covid, 44% of whom for over a year already, and NHS treatment backlogs continue to grow. While 75% of the UK population has had two Covid vaccine doses, “breakthrough infections” are common, and vaccine efficacy is limited by emerging variants and immune system functioning. It’s simple: we’re living with Covid. We still need Covid precautions.

Of all the measures the government introduced during the pandemic, masks are among the least disruptive and most effective. Meta-analyses of research show masks reduce viral spread by over 50%. They work best when high-quality, well-fitting and worn universally, not just by the clinically vulnerable. Masks are great for those who don’t realise they’re infectious, aren’t able to self-isolate or can’t socially distance. In short, mass mask-wearing – while recognising exemptions – enables people to get on with their daily lives while protecting those most at risk.

From my own experience, the UK’s abandonment of mask-wearing has demonstrably impacted the lives of sick and disabled people – yet large-scale research has overlooked this. ONS data from April shows that two in five adults in the UK are very or somewhat worried about the effects of Covid on their life, but there’s no analysis for disability or sickness. So I decided to take matters into my own hands, and poll my sick and disabled Instagram followers last week. Of 240 respondents, 93% were adversely affected by lack of masking, saying they avoided some (26%) or many (67%) enclosed public spaces as a result. Lack of masking – particularly on public transport – negatively affected their mental health, they told me, including causing depression and panic attacks and making people feel “unsafe”, “alienated”, “unimportant” and “exhausted”. There’s been a lot of talk of “mental health” and “freedom” over the pandemic to justify returns to a mask-free “normal” – do those of disabled people not matter?

View this post on Instagram

Masks have also become a lightning rod in Covid debates. “Anti-maskers” in the UK, US and elsewhere have dubbed masks “muzzles” and a violation of bodily liberties, shaming those that wear a mask as weak and conformist and even turning to harassment and assault. But even many of those of us who considered ourselves broadly supportive of lockdown and even pride ourselves on our solidarity with disabled people have been quick to abandon masks. The pandemic has thrown the ableism and individualism that are deeply embedded throughout our society into stark relief.

The idea – explicit or implicit – that “we can’t be expected to wear masks forever” is bogus. Mask-wearing can and should become an embedded social practice, just like it has been in much of East Asia for years, and has become more recently in places like Germany and Italy. Why can’t this be possible in the UK? Just because people have freely transmitted respiratory viruses in the past – flu, in a bad year, still kills 30,000 people in the UK and caused my own chronic fatigue syndrome – that doesn’t mean they should forever. We have simple technology to prevent the spread of airborne viruses – let’s use it.

There is no “normal” to return to – Covid is with us forever. And as long as it is, a lack of mask-wearing in public will effectively prohibit sick and disabled people from participating in public life. If the government won’t offer protection, the people must. Disabled people deserve not just safety but also joy, leisure, culture. So buck the ableist trend and wear a mask.

Sophie Buck is a UK-based neurodivergent and chronically ill writer, artist and founder of the magazine Autisticulture.