Keir Starmer’s Betrayal of Workers is Nothing New for Labour

Since its beginnings, Labour has been no friend to workers.

by Jodie Collins

5 August 2022

Keir Starmer doesn’t care about workers. That can be the only explanation for why, in the last few weeks, he has failed to support pay rises for public sector workers during a spiralling cost of living crisis, refused to support the ongoing rail strikes, and has threatened to sack frontbench staff who dare to join picket lines. In the face of a burgeoning MP rebellion, he’s softened on the latter– but only to protect his own skin.

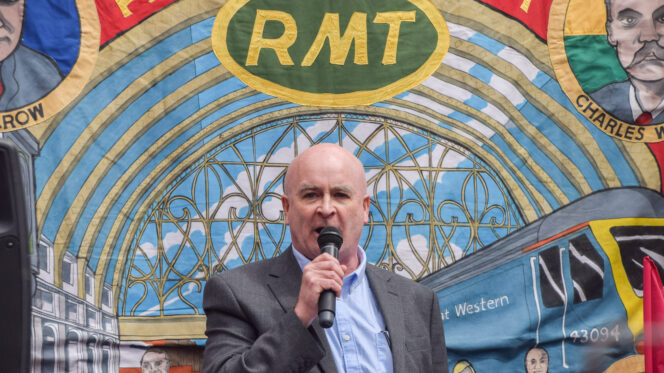

Starmer’s anti-worker posturing has led to many accusing him of betraying the spirit and history of the Labour Party. In the Guardian last week, John McDonnell asked: “What has happened to the Labour party that it can’t stand up for labour?”. Former transport minister Sam Tarry, recently sacked from the front bench for joining a RMT picket line, remarked: “We should never have been in a situation where we had an edict that you can’t join a picket line. This is the Labour party, the clue is in the name.” “If the Labour Party can’t stand up for organised labour – literally, the job they were founded to do – what’s the point of them?” questioned Novara Media’s own Ash Sarkar.

A political nostalgia has emerged in recent years, one which portrays the pre-1997 Labour party as a bastion of worker’s rights, until Tony Blair came along. In this rose-tinted history, the likes of Neil Kinnock and Harold Wilson are imagined to be standing shoulder to shoulder with striking miners and seafarers. In reality, the idea of a Labour party which unflinchingly supported workers does not correspond with historic record. Such mythology only undermines the fight for workers rights and a better society, as it maintains an illusion that the Labour party is anything other than a prop for capitalism.

Although formed as an alliance between trade union leaders, the Independent Labour Party and the Fabian Society in February 1900, the Labour Party has repeatedly proven its commitment to maintaining social order at the expense of workers. Its original constitution failed to mention the word ‘socialism’ at all, and it spent its first decade and a half as little more than a parliamentary adjunct to the Liberal Party.

As journalist George Dangerfield put it in the 1997 work ‘The Strange Death of Liberal England’: “Even its twenty-nine professed Socialists […] seemed prepared to vote with the Liberal majority, to wear frock coats, to attend royal garden parties, to become, as time passed, just a minor and far from militant act in the pantomime of Westminster.”

When millions of miners, railways workers, and women factory workers, fought against their bosses and the state during the ‘Great Labour Unrest’ between 1911 to 1914, and workers were shot dead by British soldiers on the streets of Liverpool and Llanelli in 1911, leading Labour MP Arthur Henderson and three of his parliamentary party colleagues were proposing a parliamentary bill which would make strikes illegal if the union did not give thirty days’ notice to employers. Luckily for workers, it was not passed.

In fact, the much lauded clause IV of the original Labour party constitution – which pledged to secure common ownership of the means of production – was originally drawn up by the party in 1918 to act as a bulwark against the revolutionary situation in Russia influencing the British working class. Ramsay MacDonald, Labour’s then-leader, Sydney Webb and Arthur Henderson had been disturbed by the unravelling events in Russia and the loss of control by moderate forces. They curated the party constitution, and clause IV in particular, to divert working class desire for radical change into “ordered social change by constitutional methods,” in Henderson’s words.

When Labour formed its first government in 1924, it conspicuously did nothing to dismantle the strikebreaking machinery that had been created by Tory governments. In fact, it took little time for Labour to employ such machinery itself. When confronted with transport and dock strikes, Arthur Henderson – now home secretary – revived the Supply and Transport Committee (STC), founded by the Tories in 1919 to provide scab labour and deploy troops during industrial conflict. Labour’s failure to break up the extra-parliamentary organisations like the STC or to repeal the Emergency Powers Act strengthened the hand of Stanley Baldwin’s Tory government in 1926, when it defeated the General Strike and starved the miners back to work.

However, no period in the Labour Party’s history ranks as highly in Labour left mythology as that of the post-war Labour government led by Clement Attlee from 1945 to 1951. The election of a Labour government gave hope to many workers whose lives had been ravaged by the impact of a devastating war, and it is undeniable that the introduction of the National Health Service and the welfare state under his leadership were truly transformational to the lives of ordinary people for decades to come. Indeed, the party proclaimed in their election manifesto that “The Labour Party is a Socialist Party, and proud of it.”

Yet it was a strange kind of socialism, which imposed a bloody partition on India, pursued colonial war in Malaya, and played a pivotal role in creating NATO. Indeed, Labour’s nationalisations of key sectors of Britain’s ailing post-war economy took place without any semblance of workers’ control. And when it came to industrial unrest, Attlee and his government proved yet again that Labour’s priority was maintaining social order and capitalism in Britain, and sided with the employers against working people.

It is notable that the Attlee government had declined to overturn Order 1305 – an official ban on strike action introduced during the Second World War – upon coming to power. This meant that any industrial action taken under Attlee’s government was ‘unofficial,’ which made it far more difficult to conduct negotiations, but much easier for the government to use extraordinary means to put down strikes. Not only this, but Attlee and Ernest Bevin had organised the reestablishment of the strike-breaking Supply and Transport Organisation, which was first employed to break the 1926 General Strike.

Within its very first week of existence, the Attlee government had already sent up to 4,000 troops to break up a strike by port workers at London’s Surrey Commercial Docks, who had been calling for a basic pay rise in one of the lowest paid industries. Not long after, in September 1945, a strike broke out at the docks in Birkenhead. The minister for Labour refused to meet the strikers and the government proceeded to send 21,000 troops to break the strike.

These were not exceptional cases. Attlee’s government routinely employed troops to break strikes across various industries in the years that followed – totalling no fewer than eleven occasions by 1950 – and had declared state of emergencies to deal with strikes in 1948 and 1949. In contrast, where employers had used lock-outs against workers–where employers would temporarily close factories to force wage cuts on workers–the government had effectively adopted a policy of non-intervention. The Attlee government had made itself abundantly clear whose side it was on.

So when we criticise Keir Starmer as somebody who is poisoning Labour values, it is important to assess what these values truly are. At almost every occasion that workers have found themselves in a decisive struggle against capital, the Labour party has acted to put them back inside their box, and – when in government – have hardly hesitated to use the state machinery to do so. While Labour has introduced protective legislation for workers, such as the minimum wage brought in under Blair, it is arguable that they were created more out of concern for labour market regulation than for workers themselves. And importantly, such legislation, as we have seen in many instances, is temporary and easily reversed or undermined when the demands of the market change.

Yet beyond parliamentary politics, the on-going RMT strikes have shown that a militant stance can build popular support and bring hope for long-term change for workers; that action can help overcome despondency. If radicalism in Britain is to progress it must not be held captive by a Labour party which has worked for a century to reorientate and narrow workers’ aspirations.

Jodie Collins is a historian of early twentieth century radicalism.