‘Dump Him’ Feminism Isn’t Revolutionary. It’s Callous

It’s not feminist to absolve yourself of responsibilities towards others. It’s individualist.

by Ash Sarkar

3 September 2022

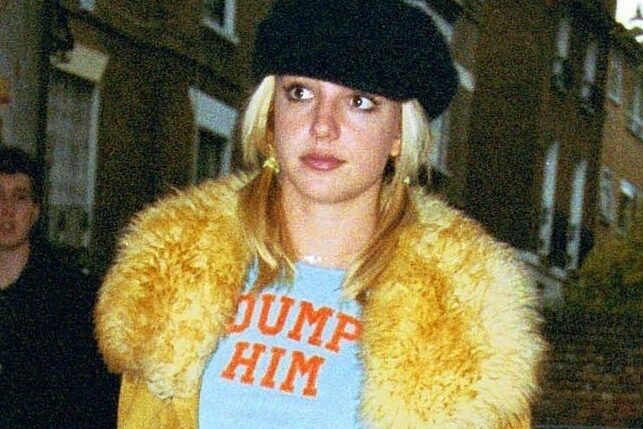

“You are enough”, “it’s a wonderful day to dump him”, “you don’t owe anyone anything”. In the canva-designed space between influencing and feminism, these are the rallying cries of young women sick to the hind teeth of the demands placed on them by gender. Recent years have seen a revived focus, driven by feminist-tinged content creators, on the burden of emotional labour – and how to be relieved of it. The solution, advocated by the likes of Florence Given, Slumflower, and their many imitators, is to simply check out of social interactions that are spirit-sapping or otherwise emotionally taxing.

To be fair, there is some good advice to be found. Though “dump him” feminism may be a little reductive, it’s a timely reminder to young women enduring relationships in which they feel disempowered that they do have ultimate agency in deciding whether or not that continues. If I had access to a time machine, I’d first kill baby Hitler, and then go back to 2016 to shake my younger self and scream “you’re not going to change him” until I got the message. But the list of things that women are told they are not obligated to do, be, or provide, range from the self-evidently reasonable (the title of Given’s book, Women Don’t Owe You Pretty invites as much disagreement as Labradoodle Puppies Are Cute) to the remarkably callous.

I’ve written before about the limitations of influencer activism, and the blasé cruelty of some of its leading lights. There’s no need to retread old ground, but the centrality of particular kinds of emotional labour as an object of examination in feminist pop culture deserves a bit more prodding. Earlier this year, a micro-scandal was born when one parent took to Twitter to complain about washing their 11-year-old child’s hair, and the 18-year-old “using me as a therapist and a crisis counsellor”. “THE AMOUNT OF EMOTIONAL LABOR I’VE PERFORMED IN THE LAST TWO HOURS HOLY FUCK.” While this was roundly mocked (and perhaps, unfairly so – who amongst us hasn’t tweeted something galumphingly stupid?), these tweets are indicative of the most absurd edge of “not my problem” feminism.

I also washed the 11yo’s hair tonight. (We’re doing the curly girl lifestyle!)

THE AMOUNT OF EMOTIONAL LABOR I’VE PERFORMED IN THE PAST TWO HOURS HOLY FUCK

— Heron Greenesmith, Esq. (@herong) April 18, 2022

The term emotional labour was coined by the sociologist Arlie Hochschild in the 1980s to describe the unpaid, interpersonal work that accompanies certain professions: Pret baristas being required to smile maniacally when taking your order, for example, or retail staff in The Kooples looking menacingly cool. Over time, the concept of emotional labour became unmoored from its origins in the world of employment, and applied to the domestic and interpersonal sphere.

Emotional labour came to describe the caring work disproportionately undertaken by women and femmes to look after, manage and nurture people within their social orbit. This care work can include obvious, discrete tasks like hair-washing and birthday-remembering, or the much more insidious business of finding yourself trapped within a particular social role. For some reason, it’s always you who’s responsible for making sure nobody gets upset at Christmas, or your partner doesn’t feel rushed into commitment, or monitoring the shared bathroom’s toothpaste levels. In mapping the language of emotional labour onto the terrain of relationships and the home, feminists found a way to articulate the invisible burden of interpersonal work thrust upon women.

The recognition that the weight of emotional baggage is unevenly distributed has, amongst some contemporary feminists, morphed into the idea that any sense of obligation is itself the enemy. There’s been a sense of mission-creep from women don’t owe you sex, domestic labour, or prettiness to the idea that women don’t owe anybody anything. “Imagine the person you’d become,” implores Given, “if you stopped trying to fix others and put that energy into yourself.” The elasticity of emotional labour as a concept means you can apply it to anything you feel is emotionally taxing, boring, or personally disruptive. Want to learn something? Google it, I’m not your teacher. Need care, love, or support? BetterHelp it, I’m not your therapist. What do we owe to others? Nothing, it seems, other than what’s identified as personally nourishing for ourselves. To issue the rebuke of “not my problem” is a revolutionary act of boundary setting. Self-care is warfare, and all that.

People were, of course, trying to square love with self-interest long before Instagram feminism came on the scene. In The Virtue of Selfishness, Ayn Rand – stretching the definition of ‘selfishness’ to encompass everything she approved of, and exclude all that she didn’t – insisted that it’s “one’s own personal, selfish happiness that one seeks, earns and derives from love.” No act of generosity, solicitude, or affection can be regarded as untouched by selfish motives. Rand gave the example of a man spending a fortune to cure his beloved wife of an otherwise fatal disease: “it would be absurd to claim that he does it as a “sacrifice” for her sake, not his own, and that it makes no difference to him, personally and selfishly, whether she lives or dies.”

But the world is full of examples where people care for others without any hope of their getting better: the man taking care of his wife who has Alzheimer’s, a woman by the bedside of her terminally-ill child. What is rational, and what is self-interested, are not always the same thing. Empathy is our ability to imagine ourselves experiencing the suffering of others, to want to ameliorate that suffering, and to feel like we have a moral duty to uphold and protect the dignity of others. That, by anyone’s definition, is emotionally laborious – and it’s not always personally rewarding. If we were to totally redirect the obligation we have towards others inwards, to “put that energy into yourself” in Given’s words, we would be turning away from the very real vulnerabilities of others. It’s not feminist to absolve yourself of responsibilities towards others. It’s individualist. Ayn Rand would be proud.

Ash Sarkar is a contributing editor at Novara Media.