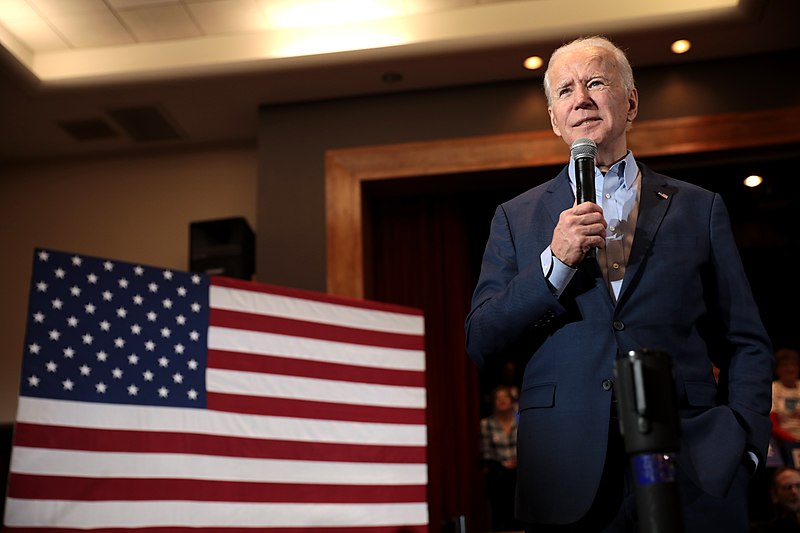

If The Democrats Lose Congress, We’re Going To See The Worst of Joe Biden

Bipartisanship is back, baby.

by Luke Savage

7 November 2022

Whatever the result of this month’s midterms, it’s unlikely to be good news for the Democratic party. Midterm elections can be unkind to whichever party holds the White House at the best of times, but the current state of play suggests that the range of plausible outcomes spans greater or lesser versions of defeat. As things stand, it would take a miracle for Democrats to retain the House of Representatives. Races in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Georgia and Nevada are all nail-bitingly tight, but barring some unexpected good fortune for candidates like Tim Ryan and Rapheal Warnock, it’s distinctly possible they’ll lose their wafer-thin majority in the Senate as well.

Either scenario raises the obvious and worrisome question of how an emboldened Republican right will choose to wield its newfound heft in Congress. The inverse question, of course, is what liberals themselves do in response and in this respect, there’s ample reason to think that defeat in the midterms will elicit a conservative turn from Joe Biden’s White House while bringing out the president’s worst instincts.

Though early prognostications about a transformative “FDR-sized presidency” were probably always too optimistic, the past two years have seen Biden buck some of his long-established centrist reflexes. His initial offering of domestic legislation included not just urgently-needed economic relief but also a raft of progressive social spending initiatives. He’s at times been vocally pro-labour and – albeit in compromised form – has successfully passed some significant climate policy. Without exaggerating the progressive character of Biden’s presidency thus far it has therefore, in certain areas, represented at least a qualified break from his own past as a committed third way Democrat, deficit hawk, and triangulator par excellence.

Throughout his decades in the Senate and vice-presidency, the unifying theme of Biden’s political outlook was a kind of dogmatic and at times quite absurd belief in the virtues of bipartisan deal-making. From the Reagan era to the end of Obama’s second term, Biden consistently sought to find common ground with Republicans and – perhaps more than any other figure in Washington – has left his stamp on many of the most noxious policy decisions of the last half century as a result.

His motivation has often had as much to do with a faith in the intrinsic value of cross-party cooperation as straightforward ideological agreement. While vice-president, for example, he struck a deal with Republican minority leader Mitch McConnell that extended unemployment insurance in exchange for maintaining Bush-era tax cuts and slashing the estate tax. For Biden, the accord was not an unsavoury compromise but, as he put it during an effusive tribute to none other than McConnell a few years later, “the only truly bipartisan event that occurred in the first two years of our administration”. “We both got beat up,” he memorably remarked, “but we knew we were doing the right thing. The process worked.”

Even the Trump era did not appear to shake Biden’s belief in the benignity of Republicans and the inherent goodness of bipartisanship. Predicting an “epiphany” within the GOP after Trump’s departure, Biden was the only major candidate in the 2020 Democratic field to talk up bipartisanship. On the campaign trail, he could be heard wistfully lamenting the decline of civility which supposedly marked his early career in the Senate, holding up no less than Southern segregationists James Eastland and Herman Talmadge as emblematic of a bygone era of consensus (“At least there was some civility. We got things done”). Elsewhere, Biden even seemed to make the case against his own party winning unified control of the government. “I’m really worried that no party should have too much power,” he remarked at the end of 2019. “You need a countervailing force. You can’t have such a dominant influence that […] you start to abuse power.”

This month, Biden may get his wish. If the polls are borne out and Democrats lose control of Congress, the new dynamic will extinguish any lingering hopes for a transformative liberal administration. But it also seems liable to inspire a retrenchment to the kind of bipartisan consensus-seeking that has hitherto defined much of Biden’s political career. In the face of many an electoral defeat, centrist Democrats have frequently responded by attacking the left and moving to the right. Presented with continued inflation and forced to govern with Republicans in the majority, it’s depressingly possible to imagine the return of fiscal austerity and even the periodically-thwarted idea of a grand bargain to cut programs like social security and Medicare – all in the interest, as Biden himself once put it, of “getting things done.”

None of this is inevitable. Lacking the necessary votes in Congress, a sufficiently ambitious and confrontational president can exercise tremendous latitude through the use of executive orders. Even unable to pass progressive legislation, Biden and the Democrats could reject cross-partisan cooperation and instead use every tool at their disposal to frustrate the virtually inevitable rightwing push for tax and spending cuts (to say nothing of the ongoing Republican assaults on voting rights and reproductive freedoms).

If Democrats do lose the midterms, however, the grim prospect of renewed Republican control may come with the added risk of a more conservative Biden administration – not unlike the one some of his critics on the left predicted when he announced his 2020 run.

Luke Savage is a Jacobin columnist and the author of The Dead Center: Reflections on Liberalism and Democracy After the End of History.