The Hidden Racism That Turned a Nazi Concentration Camp Into a Detention Centre for Muslims

Liberal 'antiracists' are ignoring mental torture.

by Arun Kundnani

23 June 2023

In the summer of 1942, the Nazi occupiers of the Netherlands began the construction of a concentration camp in the forests near the small town of Vught. The camp’s initial purpose was to act as a transit centre to hold Dutch Jews before their transportation to the death camps in Germany and Poland. The first prisoners arrived at Vught in January 1943. Three months later, Jews in all the provinces outside Amsterdam were rounded up and most of them were sent to Vught. Several hundred lost their lives in the first few months of the camp’s operation, owing to starvation, disease, and summary executions. Those who survived Vught itself were slated for deportation trains. More than 34,000 were transported from the Netherlands to the Sobibór extermination camp in Poland between early March and the end of July 1943. In June alone, the Nazis transported almost 1,300 Jewish children from Vught to the death camps. There were 140,000 Jews living in the Netherlands before the Nazi occupation. Only one in four survived.

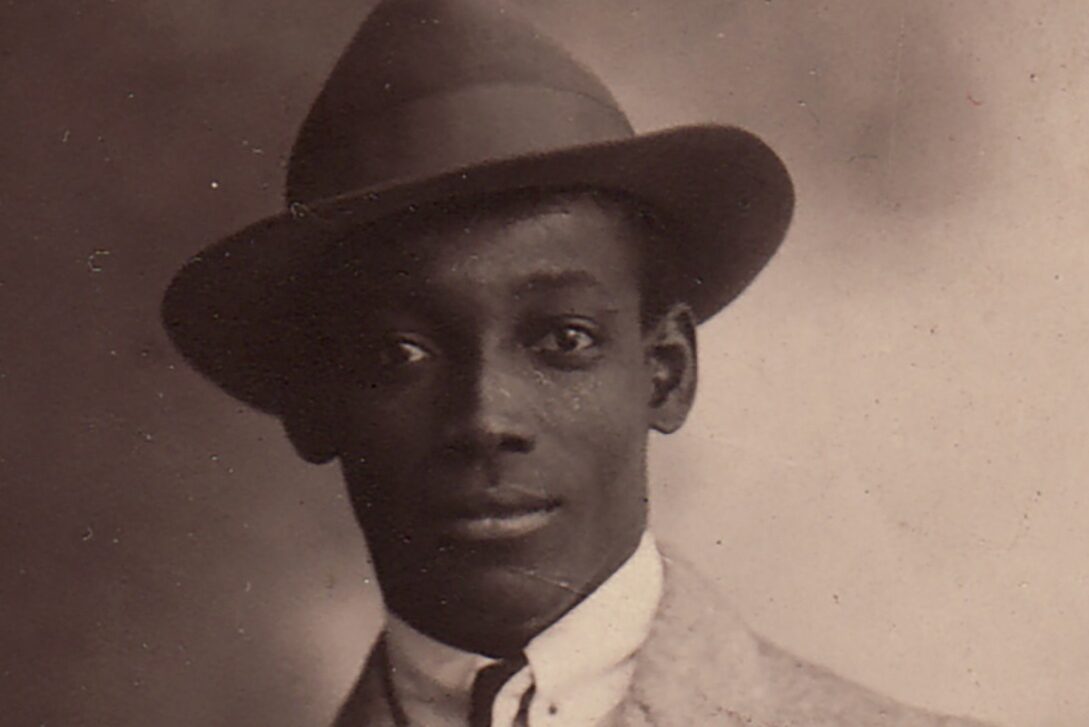

Activists in the anti-Nazi resistance were also imprisoned at Vught. Among them was Anton de Kom, who had been a leader in the struggle against Dutch colonialism in Suriname. His 1934 book We Slaves of Suriname, written in Dutch, traces the long history of resistance to European rule in Suriname, from the Indigenous “red slaves” through to the guerrilla wars waged by bands of escaped African slaves against the plantation system, and the struggles of indentured workers from India and Indonesia. De Kom demonstrated that slavery did not end with its abolition in 1863, but continued in new forms: the Dutch arranged emancipation “in such a way that the freed slaves had no other choice but to voluntarily take up the slavery which had just been legally abolished.” Under the colonial system, the various categories of workers were not truly free because they were still “forced to sell their labour-power, albeit in a different way than during the days of slavery.” As such, the plantation system’s “physical pains have mostly been replaced by mental torture, poverty, and deprivation.”

A year before the book’s publication, De Kom had organised a protest of Black and Asian workers at the governor’s office in Suriname. A mass uprising in the capital city, Paramaribo, followed. The authorities imprisoned De Kom for three and a half months without trial before exiling him to the Netherlands. There he continued his anti-colonial organising, collaborating with Indonesian students fighting for their country’s liberation from Dutch rule, and joining the underground resistance after the Nazi invasion. In August 1944, he was betrayed by an associate, and German police arrested him. After a period at Vught, he was transported to the camp at Sandbostel, an annexe to the Neuengamme concentration camp in Germany, where he died of tuberculosis in April 1945, aged 47. He was one of perhaps 2,000 Black people who died in the Nazi camps.

Another prisoner at Vught was my grandfather, Henricus van Herten, a Dutch Catholic who worked as a bookkeeper at the town hall in Roermond. He was arrested for “unlawful dealings with ration cards”, sentenced without a trial and, after two months in other prisons, was taken to Vught on 18 January 1943, when the camp was still being built. The Nazis placed him in the “a-social” category and listed his crime as “economic deceit”. By March, he had fallen ill with malnutrition and was sent to the camp hospital. On 11 May, he was released. In the years after the war, he never spoke to his children about what happened. My grandmother told them he had been in the resistance and had stolen ration cards to help Jews in hiding. However, years later, when an aunt of mine investigated her family history, she met the daughter of another deceased Henricus van Herten who had lived in the same region and had talked to his family about his assistance to Jews in hiding during the war. This discovery suggested the possibility that the Nazis had mistaken my grandfather for someone else with the same name. There is nothing in the archives to confirm what happened.

Today, a national memorial exists at the site of the Vught concentration camp. The main building is a museum with exhibits on the history of the camp and Nazism in Europe. Outside are life-size reconstructions of the camp’s living quarters, watchtowers, and barbed-wire fences. Various components of the memorial commemorate those killed at Vught or murdered after passing through it. The final part of the memorial is a reflection room where several short films convey the message that you should not be a bystander when you see others needing help. One film, entitled Not Everything Is What It Seems, presents three characters discussing stereotypes. A blonde woman talks about how people assume she is unintelligent. A white man with tattoos explains that people sometimes think of him as “white trash.” A North African man says people are surprised by how well he speaks Dutch. In the memorial’s understanding of anti-racism, we all make unfounded assumptions about others based on their appearances, but education can help us overcome these prejudices. It is a message that seems designed to make no one feel uncomfortable in a place that should be discomforting.

But more significant is the lack of discomfort at another aspect of the Vught site. Walking around the grounds of the memorial, it is impossible not to notice that alongside one of the memorial’s walls is a much taller wall, topped with barbed wire and closed-circuit TV cameras. On the other side of that wall are prison buildings, their arrangement mirroring that of the memorial’s reconstructed camp buildings. The memorial, in fact, takes up only a small part of the original concentration camp site. A larger part is occupied by a functioning prison. If you look left from the memorial’s main entrance, the tall metal doors of the prison entrance are visible, flanked by lines of people waiting to visit inmates. Many are women wearing hijabs and niqabs, a result of the fact that the Vught prison includes a high-security unit where anyone suspected or convicted of being a terrorist or “Islamic radicaliser” is automatically separated from other prisoners and held under especially punitive conditions. Because almost all of those imprisoned there are Muslims, the unit has come to be known informally as a “Muslim detention centre”.

Dutch prison authorities opened the high-security unit in 2006. Prisoners held there are isolated and confined for up to 22 hours per day. One woman imprisoned there, who was eventually acquitted of all charges, spent two full stretches – one for ten consecutive weeks and the other for three – cut off from anyone else. This kind of isolation has been a focus of research for Craig Haney, a psychologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who writes that prisoners held in long-term solitary confinement suffer effects that “are analogous to the acute reactions suffered by torture and trauma victims”. Former United Nations special rapporteur on torture Juan E. Méndez has said that, based on the medical evidence, solitary confinement for longer than 15 days can amount to torture when used during pre-trial detention or as a punishment, and therefore should be absolutely prohibited.

Adding to this mental torture in the Vught high-security unit are the regular and invasive full-nudity strip searches of inmates. So humiliating are these measures that, when they are allowed to have visitors, many prisoners choose to meet them separated by a glass barrier because that option does not require such a search. Even without the glass barrier, family visits are monitored to such an extent that they become superficial encounters. Indeed, every word and movement of the prisoners outside their cells is observed and recorded.

Approximately 170 prisoners were held in the high-security unit at Vught in its first ten years of operation. The majority were not convicted of a crime but were awaiting trial, which can take up to 27 months. Among those at Vught who had been convicted were a woman found guilty after reposting a single tweet that allegedly encouraged people to fight in Syria, and a man convicted for giving €1,000 to a childhood friend who had travelled to Syria. Soon after the unit opened in 2006, a group of prisoners held there went on hunger strike and complained they were treated worse than animals. They said they received punishments for speaking Arabic, for trying to shout to prisoners in neighbouring cells, and for refusing to cut short their prayers.

The regime of extreme isolation, humiliating searches and continuous monitoring at the Vught high-security unit is modelled on those that operate at so-called supermax prisons in the United States. Supermaxes were largely a response to the rebellions, usually Black-led, that erupted in many US prisons in the 1970s. Earlier, techniques of extreme isolation had been developed by psychologists working with the federal bureau of prisons. A mix of manipulation and coercion, they argued, could break inmates down to a kind of blank slate, upon which a new, more docile personality could be constructed.

With the global “war on terror”, the US supermax prison was globalised. The carceral sites that emerged – at Guantánamo, Abu Ghraib, Bagram, and countless other places – followed the supermax model, with practices such as prolonged and indefinite solitary confinement, sensory deprivation, permanent monitoring, force-feeding of hunger strikers and systematic secrecy. Today’s practices at Vught can only be understood as part of this global infrastructure that imprisons Muslims around the world. A site built by the Nazis to carry out the genocide of Jews now serves as a “Muslim detention centre” where people are, in effect, tortured. The visitors to the memorial at Vught are literally bystanders to racist oppression taking place on another part of the site.

What happened at Vught in 1943 and 1944 and what happens there today are, of course, not equivalent. Yet neither are the uses to which the camp has been put in these two periods entirely separable. The Nazis sought the complete elimination of European Jewry; incarceration was a means to this end. The European and US governments that implemented a global “war on terror” have a different aim. Their goal is the integration of Muslims into what they call “liberal” society. What is regarded as the cultural identity of moderate Muslims is celebrated within a framework of diversity and inclusion. Extremist Muslims, on the other hand, have their mosques and community organisations closed down, their speech criminalised, their bank accounts frozen, their clothing regulated (as with the Dutch ban on wearing a niqab or burka in certain public spaces, introduced in 2019), even their citizenship cancelled. In the cases of Afghanistan and Iraq, entire countries were invaded, occupied, and destroyed. We do not know how many men, women, and children have been needlessly killed by the US and its junior partners, such as the UK, in the “war on terror”. But the number is certainly over a million.

To understand how nominally liberal states can administer violence on this scale requires that we understand the particular form of racism that is bound up with it. Former UK prime minister Tony Blair described this violence as being aimed not at regime change but at “values change”. Influenced by neo-conservatives such as Bernard Lewis, Blair had come to believe that Muslim cultural values were so antagonistic to his idea of liberal modernity that only a war to tear apart Iraq’s social fabric would make possible the new kind of Iraq he envisioned. This was part of “an elemental struggle about the values that will shape our future […] a war, but not just against terrorism but about how the world should govern itself in the early 21st century.” According to this logic, Muslim terrorists express the deep flaws of their culture while the West’s much greater violence is a rational, even liberal, response, aimed at modifying their barbaric behaviour. Genocidal violence does not always announce itself in the rhetoric of overt hatred; it can also be hidden by the managerial language of cultural reform.

Vught is thus a place haunted by the presence of multiple forms of oppression. Nazi antisemitism instigated the construction of the original site of incarceration. Dutch colonialism led to the imprisonment of one of its detainees, De Kom. The “war on terror” shaped a new logic of confinement decades later. Echoing the logic of US efforts to stem Black-led prisoner radicalism during the 1970s, extreme isolation is today used at Vught to break down the personalities of extremist Muslims and remould them as moderate Muslims – part of a broader program of violently imposed cultural change. All of these different oppressions can be described using the term “racism”. Yet most of these racisms remain invisible. The usual assumption is that what happened in the 1940s at Vught is the defining example of racism, while what happens there now has nothing to do with racism. Thus, at a site to commemorate Nazi racism, we become bystanders to the other racisms that surround us.

To make fully visible the different forms of oppression at Vught requires that we move beyond the narrow conception that the Vught memorial implies, in which racism is an individual attitude or unconscious bias. The lesson of Nazism, on this view, is that racist prejudices, left unchecked, can be exploited by political extremists and become a threat to liberal values of individualism, rationality, and progressive reform.

But there is another way of telling the story of racism which we find not at the Vught memorial, but in the writing of De Kom. He wrote about racism in terms of the everyday colonial hierarchies through which labour is categorised and differentiated as part of nominally liberal ways of organising society – backed by the routine administrative powers of the state. For him, racism expresses itself in individual attitudes, of course, but these are themselves expressions of the deeper social and economic forces that organise the world – what we might today call racial capitalism. Only with an account of racism along these lines will we be able to understand how a Nazi concentration camp could be turned into a detention centre for Muslims.

This article is an edited extract from Arun Kundnani’s new book What is Antiracism? And Why it Means Anticapitalism, published this month by Verso.

Arun Kundnani is a writer on racial capitalism, Islamophobia, surveillance, political violence, and radicalism.