How the Guardian Lined Up Behind Starmer

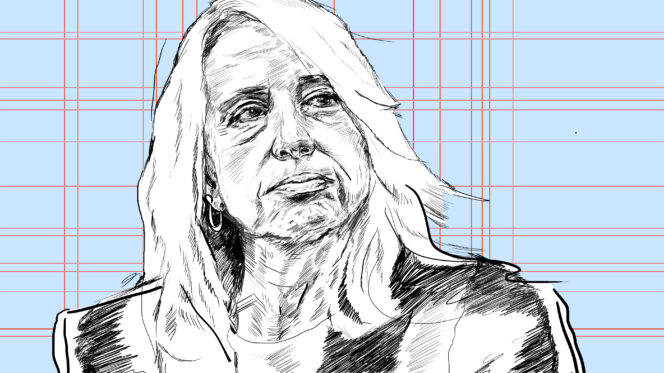

Shortly after being shipped to Sydney to head up the new Guardian Australia in 2013, Katharine Viner decided to break with a major Fleet Street tradition: her paper would not endorse anyone in Australia’s federal election. The move was widely seen as courageous and canny.

“In a digital age, news organisations which pronounce from on high the way their readers should vote are an anachronism,” read the non-endorsement (the UK Guardian’s print circulation more than halved between 2000 and 2013 from around 400,000 to 190,000, while monthly visitors to theguardian.com exploded into the tens of millions). But by the time Viner returned to London to run the Guardian’s global operation two years later, she’d changed her mind.

In the heyday of print media, election endorsements mattered – at least among journalists. “It’s the Sun wot won it” the paper famously crowed in 1992, claiming its favourable coverage and eventual endorsement of John Major had clinched the Tories’ slim victory; “If Kinnock wins today,” the paper wrote in its notorious election-day front page, “will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights.” Nowadays, leader columns generally – election endorsements included – tend to have less online currency than, say, shock-jock op-eds; it’s mostly other journalists, politicians and policy wonks who care about them. To those paying attention, however, endorsements provide an insight into the political machinations within a publication, or at least its leadership.

The way the Guardian does its endorsements is unusual. At most UK newspapers, the paper’s owners will sit down with editors-in-chief and leader writers to decide on whom to endorse at a general election. The Guardian, by contrast, opens up its endorsement meeting to all editorial staff. The practice was introduced by then editor-in-chief Alan Rusbridger in 2010, a reflection of the paper’s commitment to democracy; the Guardian puts its top job to an all-staff ballot for much the same reason. “All views are welcome,” wrote editor Viner in her invitation to the most recent meeting, “and we look forward to a civil and stimulating debate.” This debate then informs, though doesn’t dictate, the endorsement that leader-writers then write, and which Viner rubber stamps.

On 19 June – two weeks and two days before the general election – around 200 Guardian journalists crammed into a conference room in King’s Place to practise this custom. Except, the meeting was quite exceptional. Chaired by chief leader writer Randeep Ramesh, the endorsement meeting saw the paper’s most senior journalists – not only its columnists, but several of its lobby reporters – argue forcefully that the Guardian should back Starmer to the hilt or risk damaging their reputation not only with readers but also with the incoming government, much to the dismay of several of the paper’s younger journalists and journalists of colour.

The tense and rambunctious meeting reflected a paper that has historically had a complicated relationship with the Labour party, though has more recently sought to smooth things out. The result was one of the staunchest Labour endorsements in Guardian history.

A united front.

The meeting began with four journalists making the case for why the Guardian should back one of four parties: head of environment Natalie Hanman was asked to advocate for the Greens; columnist Zoe Williams for the Lib Dems; Polly Toynbee, the Guardian’s most consistent Labourite since she joined the paper in 1998, for Labour, obviously; and Ramesh for the Tories, to lighten the mood more than anything. The paper didn’t bother with Reform UK. In truth, the question of whom the Guardian should endorse was already answered: it would be Labour. The real question was whether there’d be an asterisk.

Like the Guardian’s morning conference, the floor of the election endorsement meeting is theoretically open to anyone, though in practice it’s mostly a well-attended tete-a-tete between high-profile columnists with a smattering of outside contributions (Viner maintained a studied silence, taking detailed notes). On this occasion, however, Pippa Crerar was straight out of the gate.

The former political editor of the Daily Mirror, a paper firmly aligned with the Labour right, Crerar joined the Guardian in the same role in 2022. Speaking at the meeting, she said the paper should back Labour 100%. Jessica Elgot, a former Jewish Chronicle reporter and now Crerar’s deputy, agreed. The polls were not to be trusted, Elgot said – indecision reigned on the doorstep, plus imagine waking up on 5 July to another five years of Tory Britain.

Several other lobby journalists joined Crerar and Elgot’s call for an enthusiastic Labour endorsement, leading some to suspect their interjections weren’t spontaneous. “It seemed as if the lobby had coordinated their message,” one Guardian journalist told Novara Media. Elgot and Crerar declined Novara Media’s request for comment.

Lobby journalists are known to skew right, much like the British political establishment with which it must maintain close ties. When it comes to party political preferences, however, reporters typically keep their politics close to their chest, since their job requires earning the trust of politicians of all stripes. Both Michael White and his successor Patrick Wintour, who served as the Guardian’s political editors 1990-2006 and 2006-15, were tight-lipped about their views even among colleagues, though some divined their Labour right sympathies (White’s son Sam served as Starmer’s chief of staff 2021-22).

After the election endorsement meeting, several attendees were shocked that political reporters should express their preferences to hundreds of their colleagues, and so forcefully. “If I was a lobby journalist, I would have sat that discussion out as completely inappropriate,” a longstanding Guardian journalist told Novara Media, adding: “How is the integrity and independence of [lobby reporters’] journalism under a Labour government supposed to be respected?”

Jonathan Freedland took a different tack. Expressing no great love for Starmer’s Labour, the columnist and sometime editor-in-chief candidate told the room that a lukewarm Labour endorsement would disappoint readers, who would wonder whether the Guardian would enthuse about anything if not the opportunity to end 14 years of Tory rule.

This fear that the Guardian is perceived as downbeat is one several of Freedland’s colleagues recognise. What shocked the room was his other argument: that if the paper didn’t fully endorse Labour, the Starmer administration would not take it seriously. Columnist Nesrine Malik rebutted Freedland, though not by name: the Guardian was a paper, she said, not a political party.

“People were just gobsmacked afterwards,” one longstanding Guardian journalist told Novara Media, “that a newspaper columnist said if we didn’t go swinging 100% in support of Labour in the election, we, a newspaper, would lose credibility with the government.”

After pushback from several younger journalists and journalists of colour, including Malik, Owen Jones, Aditya Chakraborty and Joseph Harker – the room was split roughly 50/50 between those who felt the paper should endorse Labour fully, and those who felt they shouldn’t or if they should it should be heavily hedged – the Starmerites won decisively. If there had been a sense in the room that the once influential Freedland, who helped steer much of the paper’s line on Corbyn, was now losing the argument among colleagues, that was not reflected in the leader.

While admitting that Starmer could do more to flesh out his thin manifesto, mentioning in passing his “timidity over Gaza” and blaming “intense factionalism” – rather than anyone in particular – for “avoidable messes over candidate selection”, the Guardian’s election endorsement made clear that the paper “would vote, with hope and enthusiasm, for Labour”. This is not how Guardian endorsements usually sound.

“This is the ultimate Guardian comfort zone,” said one senior journalist for the paper, “You say like we’d like [the Labour party] to be bolder … instead of being like, ‘These are people are actually rather rightwing”.

Critical friendship.

The notion that the Guardian is by default a pro-Labour paper is entirely ahistoric. The Guardian has never resolved the tension between the Liberal tradition from which it grew and the Labour movement that mostly superseded it in the 20th century, nor has it sought to. In the 106 years the Guardian has been pronouncing on general elections, it has rarely done so wholeheartedly. In fact, most of the endorsements the paper has given have been emphatically uncommitted.

“For our own part we care very little whether, with a combined majority, the Liberal party takes office with Labour support or the Labour party with Liberal support,” it wrote in 1923. In 1951, the party supported Churchill as the “lesser evil”. In 1992: “We would prefer, however narrowly, a majority Labour government on Friday.”

1997 saw the paper briefly swept up in Blairmania, insisting that Labour must be handed a “large mandate” though still acknowledging the “claims and achievements” of the Liberal Democrats. The paper promise it would take New Labour on its merits and turn against it if necessary. It made good on this commitment in 2010, backing the Lib Dems.

The Guardian backed Labour in 2015, under Rusbridger, though for mostly pragmatic reasons. “This newspaper has never been a cheerleader for the Labour party,” it wrote. “We are not now. But our view is clear. The overriding priority on 7 May is … to stop the Conservatives from returning to government and to put a viable alternative in their place.”

The party’s defeat prompted a leadership contest, something on which the paper didn’t routinely comment (the Guardian was one of the few papers to withhold judgement on Miliband v Miliband, though it did recommend Tony Blair for the Labour leadership in 1994). In the end, Viner decided the paper must offer an endorsement, and endorsed Yvette Cooper.

The Guardian remained nominally loyal to the Labour party even after its preferred leadership candidate floundered, backing Labour in 2017 and 2019, though both times with hefty caveats. The latter endorsement was particularly backhanded, regretting Corbyn’s “low-key and troubled campaign”; twice mentioning his “gigantic offer” of “a state so large it seems impractical”; condemning his “factionalism, his lack of a campaign narrative and his repeated overpromising”; highlighted his “unpopularity”; and bewailing his “obdurate handling of the antisemitism crisis”. Though technically endorsing Corbyn, many saw the piece as a continuation of the paper’s unsympathetic coverage of the leader.

This time, Elgot and Crerar argued, the paper could not afford to be so dispassionate – a Starmer win was not the done deal the polls made it seem, they told colleagues. Sure enough, Starmer’s flaws were all but absent from the endorsement leader, whose shift in tone reflected the paper that had slowly gravitated towards, and is now firmly behind, the Starmer project.

In a statement sent to Novara Media, a Guardian spokesperson said: “The wide array of claims put to us are riddled with inaccuracies and unsubstantiated claims about our journalism and our journalists. As always, the Guardian held a meeting for all our journalists to discuss our leader line ahead of the election. Debate is a healthy part of that journalistic process. Our outstanding, award-winning politics and opinion teams will continue to hold all parties to account.”

Beat sweeteners.

There is an apocryphal story at the Guardian that around the time of the 2021 Labour conference, Viner had a run-in with Keir Starmer. The Labour leader reportedly complained to Viner about how the Guardian’s opinion pages covered him; one Rafael Behr column, headlined ‘Labour looks aimless because it’s already searching for Starmer’s replacement’, had surprised even the paper’s leadership in its dismal prognosis. Our news desk has been kinder to you than our opinion desk has, Viner is supposed to have assured Starmer. While the story’s veracity is unclear, she would have been right to say this.

Pluralism is one of the liberal values most prized by the Guardian – and throughout the Starmer years, the opinion pages have mostly reflected it. Since he seized the Labour leadership in 2020, the paper has not shied away from publishing damning opinion pieces about him and his party – although critical voices are often guest contributors, since the majority of the paper’s most established columnists, notably Toynbee, Freedland and the formerly sceptical Behr, are to varying degrees sympathetic to Starmer. Perhaps counterintuitively, the Guardian news desk cares less for such journalistic balance.

From a journalistic point of view, this makes sense. The Corbyn administration viewed all mainstream media outlets – the Guardian included – as hostile, despite the fact that some of its key figures (notably Corbyn’s communications director and former Guardian opinion editor Seumas Milne) were drawn from its ranks. Starmer, on the other hand, sees his natural journalistic home at the Guardian, hence his supposed annoyance with Viner.

Unlike with Corbyn, then, there’s an incentive for Guardian journalists to run “beat sweeteners” on Grey Labour, puff pieces designed to curry favour with politicians who might offer them stories in return. At the morning conference on the day of the election itself, a junior lobby journalist named Kiran Stacey expressed his belief that a Starmer leadership would naturally produce more stories for the Guardian.

Viner seemed disconcerted at the jubilant tone of the conference. We’re going to hold them to account too, right, she reportedly said – and maybe unearth some scandals?

“The senior editors want to be, and Kath Viner wants to be, in with the new government,” one Guardian veteran told Novara Media. “There’s a sort of well-trodden path with the Guardian that when a Labour government is elected, they can’t control their initial enthusiasm for their improved access to power.” They doubted Stacey’s certainty that a Labour government would result in improved access or better stories. (Stacey declined to comment for this story.)

“They’re kind of imagining – wrongly, by the way – that because they’re the Guardian, and because they’ve supported Keir Starmer’s Labour loyally from the start, they’re going to be rewarded with loads of scoops and exclusives. But on past experience that won’t happen, it will be more like some targeted early doors press releases … the Guardian’s lobby journalists think they’ll be in journalistic clover, but I doubt they [will be].”

Stacey’s current colleagues aren’t convinced of the usefulness of strategic Starmerism either. “I think it’ll help them get the sort of stories that actual people don’t give a shit about,” one of them told Novara Media. “Really shit interviews with somebody for half an hour where you sit down over coffee, then transcribe their quotes … [or] get the drop on the policy announcement 24 hours earlier.”

This prediction appears to be on the money. One recent fawning headline from diplomatic editor Patrick Wintour heralded ‘Operation reset: Lammy’s mission to reconnect gets off to flying start’. The same day, Wintour published an exclusive claiming that Lammy planned to drop the UK’s challenge to the International Criminal Court over its plans to issue an arrest warrant for Israeli prime minsiter Benjamin Netanyahu; a week later, the Israeli newspaper Maariv reported he’d U-turned.

“The irony,” the Guardian journalist added, “is [that] Pippa is a fantastically good reporter … and I don’t think [hers] are the kinds of stories which will ever be particularly shaped by whether or not we’re being nice enough to them.”

That’s certainly borne out by history. Rusbridger was more ruthless than Viner in ruffling the feathers of the establishment, including the fourth estate; the Guardian was the paper that broke the phone hacking scandal.

Despite endorsing New Labour on all three occasions it contested a general election, between polls the Guardian fiercely scrutinised Blair and Brown and still got big scoops, forcing Peter Mandelson – or “Petie”, as he’s known to friends – to resign not once but twice (the bulletproof Blairite has since reincarnated as a behind-the-scenes guru to Starmer). So infuriated was Blair by the Guardian’s hostility that he briefly entertained a party-wide boycott. Thankfully, those days of animosity are over.

A key difference between Rusbridger and Viner are the circles they run in. Though drawn from a more elite set, Rusbridger generally steers clear of politicians, more likely spotted at a Wagner concert than a ritzy garden party. Viner, a lower-middle-class grammar-school girl with a deep sense of unbelonging, wants fervently to be taken seriously by those in power; she was reportedly crestfallen after being overlooked for a soirée at the Starmers’. “My dinner party invites are at stake here,” journalists joked to one another after the endorsement meeting, parodying their pro-Starmer colleagues.

Hear no evil, speak no evil.

These days, the Guardian news desk is thought of within the paper as strongly sympathetic to Starmer, glossing over his failures and amplifying his successes. After former Guardian chief political correspondent and now BBC Newsnight political editor Nicholas Watt tweeted that Starmer had effectively blackmailed Commons speaker Lindsay Hoyle into calling Labour’s Gaza ceasefire amendment (Starmer claimed he “simply urged” Hoyle to have “the broadest possible debate”), Stacey praised Starmer for “avert[ing a] Gaza ceasefire vote crisis”. When Starmer overrode party democracy to bar dozens of leftwing candidates from standing for parliament before subsequently parachuting in his own, Elgot welcomed his “tak[ing] aim at loose cannons with his tight control of Labour selections”.

“Pre-election … I do think some of our news coverage is a little craven,” one Guardian journalist told Novara Media. “And I’m always a bit surprised honestly at the Guardian, that during election campaigns, we do just revert to ‘We’re really great, says Labour minister.’ There’s a … weird, determined artlessness of the way that lobby and national news teams think about this stuff.”

In the final days of the campaign, the Guardian reluctantly covered – after much pressing from colleagues – shocking candidates such as Luke Akehurst. The paper’s profile of Akehurst, a professional Israel lobbyist who once described an anti-Zionist Black Jewish woman as suffering an “inner conflict”, quoted mostly those sympathetic to Akehurst, euphemising his social media activity, which included saying the “hysterical” Guardian columnist Polly Toynbee should “put a sock in it”, as “punchy”.

The Guardian ran just a single piece on the scandal of 103 lobbyists standing for Labour, leaving it mostly to smaller publications such as openDemocracy, The New Statesman and Novara Media to bring the story to light.

Privately, Guardian journalists remain tough on Labour. About a week before the election, Streeting came into the Guardian office and was given a thorough grilling (asked about Starmer’s ditching his 10 pledges, Streeting said he hadn’t supported them anyway). In public, it’s a different story.

During the election, the paper shrank from issues that could have hurt Starmer, notably Gaza – sometimes for its own sake, at other times seemingly for Starmer’s. The paper’s political correspondent Aletha Adu initially planned to profile Andrew Feinstein, the pro-Palestine Jewish independent candidate contesting Starmer’s seat in Holborn & St Pancras (he eventually won 19% of the vote). The piece was spiked by higher-ups. The paper did, however, profile Leanne Mohamad, the 24-year-old who came within 528 votes of unseating now-health secretary Wes Streeting.

On Gaza and other issues, the paper often reprints verbatim Labour lines even when factually dubious, such as soon-to-be home secretary Yvette Cooper’s claim made the day before the election that Labour candidates were suffering “harassment” and “intimidation” in “pro-Palestine areas” – among the paper’s examples of this was a teenage Labour canvasser being told by an opponent she would “never wash off the blood of dead Gazan children”. The Guardian later regurgitated Cooper’s analogising of these “disgraceful scenes” with the attempted assassination of Donald Trump. Elsewhere, the Guardian has reported party commitments as prophecy: ‘Keir Starmer and Angela Rayner to kickstart new era of devolution’ read one headline, a sentence that might usually be followed by “Labour claims”.

At times, the lobby appeared to operate almost as an extension of the Labour press office. After Adu published her profile of Labour’s Clacton candidate Jovan Owusu-Nepaul in which he complained of being insufficiently supported by Labour, Adu’s colleague Elgot tweeted a quote she had personally sought from Starmer saying “We’re not backing down in Clacton”. Six days later, Black British newspaper the Voice reported that a tearful Owusu-Nepaul had indeed been stood down by Labour. The Guardian’s pre-election politics podcast was illustrated with a picture of Crerar beaming beside Starmer.

The paper has not entirely avoided criticising Labour: it has already been hammering the new government for maintaining the two-child benefit cap, an issue it highlighted throughout the election campaign. Its lobby correspondents have shown scepticism about Labour’s meagre spending plans – though, says one senior Guardian journalist, the paper rarely joins the dots between the two.

“In the case of the environment, there is a willingness to say, ‘These are our principles, and if someone is falling short of them, we are going to really pursue it’ – but we don’t really cover Westminster this way,” they said.

They added that they doubt the Guardian would ever break a story as ruinous for Starmer as partygate – which Crerar helped to unearth at the Mirror, though rightwing papers including the Times also contributed to it – was for Johnson. “We’re not Pravda, we [wouldn’t] pretend it’s not happening,” they said. “[But] is it likely that [the reporting on] a scandal in the Labour government will be led by the Guardian? Obviously not.”

Rivkah Brown is a commissioning editor and reporter at Novara Media.