Former Priory Patients Tell of ‘Traumatic’ Privatised Mental Health Treatment

Nearly £800 a night.

by Harriet Williamson

27 March 2025

“During my six weeks on an adult ward in The Priory, I received no therapy at all. It cost the NHS nearly £800 a night for me to be there.”

The first time Hannah was admitted to a Priory Group hospital, she had just turned 16 and was in the throes of severe anorexia. “I spent just over 18 months there,” she says. “I didn’t go home for the first year – and for the first few months, I wasn’t allowed outside.”

Hannah describes being restrained and forcibly tube-fed by staff four times a day for approximately 14 months. A spokesperson for the Priory says that force-feeding and restriction of movement can be necessary in cases of acute eating disorders. But Hannah experienced it as traumatising. “It was very rough and done with very little compassion or explanation of what was happening to me,” she says.

“Staff would repeatedly refer to me as my room number as opposed to my name. ‘Room number nine, you need to go for your medication now’ or ‘Room number nine, you haven’t done this.’ It’s beyond dehumanising.” (A Priory spokesperson said this is “not practice we would ever expect to see”, and that both sites referenced are rated “good” by the independent regulator and practice is routinely subject to audits and assessment internally.)

“Within those walls, you’re just a diagnosis – they don’t see you as a person with a life and so much more to you than that, and when you’re in there for so long, you start to believe it too,” Hannah says.

Yet Hannah’s ordeal was only just beginning. Six years later, she was admitted to another Priory Group facility as a 22-year-old. Hannah tells Novara Media that her experience there was “a lot, lot worse”.

“I received no treatment whatsoever,” she says. “From the minute I was brought to the ward to the moment I left, I received no talking therapy. It was like a holding cell. I was sedated on a whole cocktail of medication where I had no say in what I was taking.”

The Priory says that at the time, the hospital team included a range of specialists, a therapeutic timetable and a therapy team which encouraged engagement at sessions specially designed for the patients including fitness, art therapy and group therapy.

Now 26 years old, Hannah – who chose to give only her first name – is one of the organisers of activist group Mad Youth Organise. Hannah agreed to speak to Novara Media and relive what she calls her “traumatic, negligent and violent” experience of the Priory because, she says, it is “not an anomaly”.

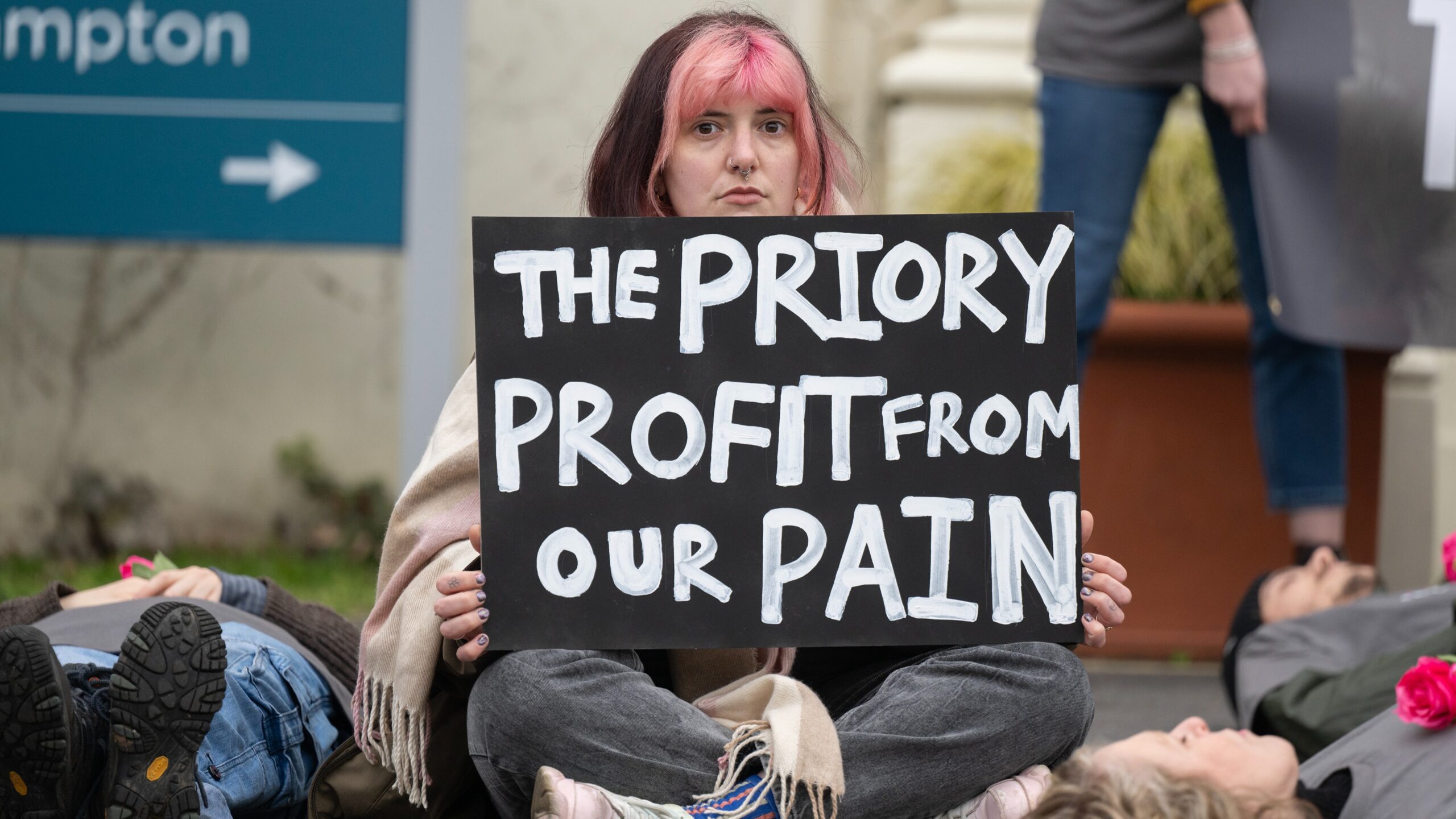

Supported by the patient-led anti-privatisation group Just Treatment, Mad Youth Organise is taking aim at what it believes are the societal causes of young people’s distress, and the corporations profiting from it. Its manifesto highlights the urgent need for a “holistic understanding of madness” that recognises the impact of austerity, dead-end jobs, zero hours contracts, unstable housing and big tech.

Everyone in the group has experiences of “madness” – the group makes a point of reclaiming the term – and its outlook is anti-capitalist. Mad Youth Organise is calling for the decommodification of essential services, the shutting down of extractive industries fuelling the climate emergency, curbs on corporate power, the vote for 16-year-olds, and that corporations financially compensate affected communities.

During Children’s Mental Health Week in February, Mad Youth Organise staged demonstrations and die-ins at the London headquarters of Meta, the Home Builders Federation, Shell and the Priory Hospital Roehampton in southwest London, the flagship facility of private healthcare provider the Priory Group – which it says is profiting from the UK’s dangerously privatised mental health system.

£2bn.

Often when leftwingers speak about Britain’s National Health Service, they focus on the looming threat of privatisation. But private providers are already through the NHS’s door in a plethora of areas – and mental healthcare is one of them.

As capacity in NHS inpatient care for mental health has dwindled, with number of NHS beds available in the UK more than halving from 50,300 beds in 1998 to 23,300 in 2019, the private sector has doubled its capacity – from 5,400 beds to 10,100 beds in the same time period – although this private capacity has only offset part of the decline.

In 2024, the NHS spent more than £2bn – 13.3% of its total mental health budget – sending mental health patients to private hospitals. This was £279m more than in 2023.

The biggest beneficiary is the Priory Group, the largest private provider of mental health services to the NHS, with 290 facilities across the UK. Next is Cygnet Health Care. Between them, the Priory Group and Cygnet account for more than 68% of the NHS spending on private mental health hospitals according to healthcare consultants Laingbuisson – and the entrenchment of private providers is only set to deepen.

Research by business management consultants Mansfield Advisors has found that although margins for private mental healthcare providers have declined, “margins remain between 15-20% and sufficient to attract extensions of existing capacity, if not necessarily new entrants outside specialist niches”. In other words, private companies can still be incentivised by profit to increase the number of beds they provide.

In 2021, the Dutch private equity group Waterland agreed to acquire the Priory Group from former owners Acadia Healthcare – a US chain of clinics – in a deal valued at £1.1bn. Waterland has said it plans to combine the Priory Group with Median Group, a private mental health provider based in Germany, to create Europe’s leading rehabilitation and mental health services provider.

With an annual turnover of over £700m, over 90% of the Priory Group’s revenue comes from the British taxpayer, which pays handsomely for its services: according to Laingbuisson, the NHS pays up to £786 per day per patient for a private bed in a secure unit, amounting to more than £286,000 a year.

For Hannah, a gentle, softly-spoken and thoughtful young woman who spent nearly two years of her life in the Priory Group hospitals as an NHS patient, that money bought a “very isolating, terrifying experience”.

Hannah tells Novara Media that for her, being an NHS patient at a Priory Group hospital “makes you madder”. She says, “As well as the deep scars of trauma it gives you, it takes you away from all the things, including the community of family and friends, that are integral to supporting me to be well and stable.”

In fact, Hannah partly attributes her readmission to hospital in 2021 after experiencing what she describes as a “psychotic episode”, to her first experience at a Priory Group hospital.

“The fact that I was hospitalised later as an adult, a lot of the reasons for that came from my time in a Priory hospital when I was 16 and 17,” she explains. “It felt like I was back in this prison of all of the things that made me unwell. I couldn’t leave for six weeks with all the triggers and reminders of where my trauma had come from. It was horrible.”

Mad Youth Organise chose the Priory as a protest target because members share similar experiences of inpatient treatment in Priory facilities.

‘Unless you have the money to pay privately, you will receive no treatment.’

May Gabriel is a fellow Mad Youth Organise campaign leader. They have a complex case history involving OCD, depression, anxiety and attempted suicide. They were an inpatient in four different Priory Group facilities – Priory Bristol, North London, Ticehurst and Roehampton – between the ages of 14 and 29. Speaking to Novara Media, Gabriel – who is neurodivergent – says they were sedated with benzodiazepines in lieu of therapy. They add that a staff member told them that the reason was “they didn’t have enough staff”. The Priory says all medications including benzodiazepines are only prescribed by a qualified medical professional, based on a patient’s medical need and regularly reviewed.

There are two types of patients in Priory Group facilities: private and NHS. Both should follow National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) guidelines.

“The difference in the standard of care I’ve seen between private Priory wards and NHS Priory wards is stark,” Gabriel says. “Unless you have the money to pay privately, you will receive no treatment – you will just receive drugs. In my three admissions to Priory Ticehurst [a Priory Group facility in Sussex], not once did I speak to a therapist.

“Care for NHS patients is awful. Your main contact is with healthcare assistants. They tend to have done basic online training, the mental health component of which is very, very minimal, so they don’t have the skills needed to deal with people in crisis, or just to deal with anyone with neurodiversity.”

The Priory says, “Private mental healthcare is typically for patients with lower acuity conditions who are not detained under the Mental Health Act, or cared for on a secure ward. Whether you are an NHS or private patient, the same clinical standards, such as Nice guidelines, are followed as appropriate for a patient’s condition.”

Gabriel recalls one particular episode while they were an inpatient at Priory Bristol to illustrate her experience. “I was put in a face-down restraint while having an autistic meltdown because I was sitting in the corner of my room and they wanted me off the floor, so they dragged me onto the bed and restrained me. They were agency staff who didn’t know how to handle it – I was just sitting in the corner, rocking back and forth, listening to music. I’ve been restrained by five grown men before as a 15 or 16-year-old.”

The Priory says that all staff who support patients receive comprehensive training and that agency staff receive “equivalent induction training as substantive staff”. Statutory guidance states that restraint is sometimes necessary to secure the safety of patients and staff, it should “only ever [be] used proportionately and as a last resort”.

However, the improper use of restraint has been documented in Priory hospitals across years of Care Quality Commission (CQC) reports. In 2020, a former teenage inpatient at Priory Bristol spoke out about her traumatic experience, which included “being put in the seclusion room for long periods (a locked room used to calm down patients), often being sedated or restrained, and feeling like there sometimes weren’t enough staff to keep patients safe”.

A 2018 inspection of child and adolescent wards at Priory Hospital North London found that staff “did not understand what constituted restraint”, there was “inconsistent recording of restraint of young people” and a “lack of planning of how to support young people in the least restrictive way possible”.

In 2020, Priory Roehampton’s specialist eating disorder service was downrated from “good” to “requires improvement” after a CQC found that staff had “acted inappropriately” by cutting a patient’s hair against their will under restraint, meaning that the service had not safeguarded the patient from “improper treatment which was degrading”.

Gabriel says, “I see so much of my madness and my illness as being a direct result of my experiences in the Priory Roehampton as a child.”

They add that what they saw as the staff members’ insufficient training meant they felt responsible for their fellow patients: “At quite a young age, you have to start becoming responsible for your friends’ lives because you can’t trust the staff members to keep them alive.”

A 2011 letter seen by Novara Media from the NHS children’s commissioning manager details the specific areas of concern raised by Gabriel’s mother about the management and the quality of Priory services during two admissions the previous year. One of these areas of concern is that, in the context of group therapy, “there was a clear message given that the patients should ‘look after each other’”, that May Gabriel “felt responsible for the other patients” and that this message “was inappropriately given to young people struggling with their own issues and therefore not in a position to ‘look after’ others”.

“By the age of 17, the amount of [suicide] attempts of my friends that I’d stopped was well into double figures,” Gabriel says. “I remember one time in particular, I was really worried about one of my friends, and I tried to open her door but it was locked. All the staff were just in the kitchen, playing music and having a party. I went and started banging on the door, and they told me to go away. I said, ‘So-and-so’s room is locked.’ And they were like, ‘Oh, give us five minutes’. When they went in, my friend was about to hang herself.”

The Priory says patient safety is their first priority and that Priory provides vitally-needed, safe and high-quality services to the NHS and private patients as a partner in the health and social care system in the UK.

The latest CQC report on Priory Roehampton’s child and adolescent mental health wards rated the service as “good” overall but reported that despite the provider being found to be in breach of regulation regarding person-centered care in 2023, the provider was still in breach with further improvements necessary. The assessment involved the interview of five patients with one saying “they felt staff were rough during restraints”.

“Staff just weren’t responsive,” Gabriel says. “Instead of there being bad apples, it’s that there are some good apples – I feel the majority are bad. And I don’t think it’s that they mean to be bad. I think it’s that the system is set up in a way that they can be bad.”

In 2023, two former members of the Priory Group’s senior management told the BBC there had been “a constant battle” over recruitment and retention at the Priory, so they were “struggling with a shortage of nurses”.

“We were told some potential recruits had no interest in working with patients who had mental health conditions, while some wards were running on 100% temporary agency staff, meaning no continuity of patient care.” According to the two whistleblowers, some agency staff would do another job elsewhere, then come to the Priory for night shifts and sleep on duty.

They felt the Priory Group wanted savings to be made and said “they always used to say we need to shave head count and increase productivity”.

Criminal penalties.

While historically Priory Group had a reputation as the glitzy private treatment facilities used by celebrities like Kate Moss, Robbie Williams, Eric Clapton and Amy Winehouse, more recently Priory Group has gained a reputation for the large numbers of people that have died on its watch.

Over the past 15 years, at least 44 people have died while in the care of the Priory Group. That number has increased rapidly: a 2022 Times investigation found that the number of reported deaths, including from natural causes, at Priory Group sites rose by about 50% between 2017 and 2020. The group has repeatedly been fined hundreds of thousands of pounds for breaching the Health and Safety Act.

In 2019, the Priory Group was fined £300,000 after pleading guilty of breaching the Health and Safety Act following the death of Amy El-Keria in one of its hospitals in 2012. She was just 14-years-old.

El-Keria’s mum Tania said: “Our Amy died in what we now know to be a criminally unsafe hospital being run by the Priory. This was Amy’s first ever hospital admission. She was alone, far from her home and her family. By day two she had been restrained by staff. She went on to be restrained many more times including on the day before her death, with forced sedative injections applied against her will.”

In 2022, three young women – Beth Matthews, 26, Lauren Bridges, 20, and Deseree Fitzpatrick, 30 – died within eight weeks of one another at Greater Manchester’s Priory Hospital Cheadle Royal. Another young woman, 20-year-old Amina Ismail, was found dead in a bedroom at the hospital a year later.

In 2023, Priory Healthcare Ltd was fined £140,000 after it pled guilty to breaching the Health and Safety at Work Act in its treatment of Francesca Whyatt, 21, who died at the Priory Hospital Roehampton in 2013.

Last year, the Priory Group received its biggest criminal penalty to date for failing patients. In March, the company was fined £650,000 after admitting to criminally failing 23-year-old Matthew Caseby, who escaped from the Priory Hospital Woodbourne in Birmingham in 2020 and later died after being hit by a train.

In December, Matthew’s father told The Telegraph he believes the NHS is “like a crack addict” when it comes to private providers. “It outsources the most vulnerable people into Priory hospitals, even when that care is rated as being inadequate,” Richard Caseby said. “The NHS don’t really want to know too much about what is happening in Priory hospitals because they’d then have to do something about it.”

Requires improvement.

The latest inspections by the CQC of two of the Priory Group hospitals mentioned above – Cheadle Royal and Woodbourne – marked them as “requiring improvement”. Despite the Priory Roehampton being rated “good” overall, its acute wards for adults and psychiatric intensive care units were marked as requiring improvement.

The Labour government appears to have little interest in stopping private healthcare providers making bank from the NHS – even those endangering patients. In January, the Labour government announced that private hospitals would provide NHS patients in England with one million extra appointments, scans and operations a year in a drive to slash waiting lists.

“Where there is spare capacity in the independent sector we will use it. We have agreed that we will work with them, and they will work with us to cut NHS waiting times,” health secretary Wes Streeting said. “The independent healthcare sector isn’t going anywhere, and it can help us out of the hole we’re in. We would be mad not to.”

People like Hannah and Gabriel, with lived experience of private healthcare as NHS patients, disagree. “Even like ten years on from when I was 16, those memories and experiences still haunt me every day,” Hannah says. “I lost a friend who was in a Priory hospital with me, and there’s not a day I don’t think about her and how she was let down by the Priory. (The Priory says that an inquest and serious case review into the incident pointed to a system-wide issue for NHS and community services, and that it has improved its services since then.)

“I have nightmares, certain triggers, things I can’t be around from my experiences there,” Hannah adds. “I feel like I lost out on my formative teenage years. I was locked away.”

‘The Priory causes madness.’

May Gabriel and Hannah met in a Priory hospital and out of their shared experiences has come not just friendship, but the energy for activism. “Sometimes we look at each other and we’re like ‘how did we get here?’” Hannah says.

Mad Youth Organise is calling out specific corporate sectors and individual corporations at a time when mental health awareness weeks are often dominated by individualistic narratives, which disregard systemic factors and the conditions young people are living under that drive psychological distress.

Gabriel says that the Priory Group is a focal point for the campaign because of its dominant role in NHS mental health provision. “We’ve got a whole group of young people who have been patients in Priories or similar private facilities,” they explain.

“There’ve been whistleblowers over the past decade, there have been documentaries – the information is out there. But the validity of our voices is often diminished because we’re all mad. The Priory causes madness, it causes trauma.

“We really want to shine a light on the kind of injustice and harm that the NHS is spending millions of pounds on,” Gabriel continues. “The Priory is harming young people and adults who are severely unwell for profit. It needs to stop.”

Hannah says, “I want more young people to understand that maybe our madness is not a personal failure; perhaps our madness is a response to the intolerable conditions of capitalism driven by corporations chasing pay cheques, as opposed to something that’s wrong inside us.

“I feel like if the NHS’s budget went towards community care and early treatment before people reach crisis point, that would be a much better use of the money – but I don’t believe that’s in the Priory’s interests.”

The Priory says, “It is wrong to assert that we seek to profit from extending the duration of admissions and would only do so where there is a clear clinical need as assessed by the multidisciplinary team at the hospital, working closely with families and commissioners.”

A Priory Group spokesperson told Novara Media, “These reports contain serious factual inaccuracies and unfounded allegations which we dispute and have challenged. However, we take any concerns raised about our services extremely seriously and would encourage the patients involved to contact us directly so we can investigate fully, involve them in the process and provide a full response.

“We are regulated in the same way as NHS providers, with 86% currently rated as ‘good’ or better by independent regulators – this is above the national average which includes NHS services. With regards to costs, it is inaccurate to suggest the independent sector is more expensive than the NHS without understanding the full cost to the NHS of providing the specialist facilities and staffing to support increasing numbers of complex, acute mental health patients across the country.”

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email [email protected], or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

Harriet Williamson is a commissioning editor and reporter for Novara Media.