How Labour Is Using Biased AI to Determine Benefit Claims

A DWP director said: ‘You have to [have] bias to catch fraudsters.’

by Harriet Williamson

15 April 2025

Imagine, for a moment, that you’re applying for an incapacity benefit. You’ve gone through the process of sharing humiliating and distressing details of your health struggles, reliving how affected you are on your very worst days. You are in dire need of financial support. You desperately hope that somebody will hear you out and approve your claim. But 10 days later, you receive a rejection. Who made this decision? A computer did. An AI tool decided you’re not actually sick or disabled – and it took your age, marital status and nationality into account when doing so.

This is the world that Labour is creating. Secretive AI tools are already deeply embedded in benefits processes that affect the lives of millions of the poorest and most vulnerable people in Britain – many of whom are now being subjected to brutal health and disability cuts under a Labour government. And – even worse – bias is baked into these algorithmic systems, making them more likely to incorrectly label claims made by people with certain characteristics as potentially fraudulent.

The idea of an AI that helps determine people’s futures exhibiting prejudice may sound scary, but it doesn’t seem to bother the DWP. Far from being horrified, in January last year, DWP change and resilience director general Neil Couling – now director general, fraud, disability and health – admitted on record that not only are the algorithms used to flag people’s claims as fraudulent biased, but that he thinks bias is needed.

Couling responded to a question in a select committee evidence session about algorithmic bias, saying: “The systems do have biases in; the issue is whether they are biases that are not allowed in the law, because you have to [have] bias to catch fraudsters.”

While the DWP’s current policy is that no final decisions are made without, in their words, “a human in the loop”, new Labour legislation currently making its way through parliament means that the incentive for this to remain DWP policy will be taken away.

After pushback from disability justice and privacy groups, Labour scrapped the Tories’ dystopian data protection and digital information (DPDI) bill, only to replace it with their own version – the data (use and access) bill. Far from being an improvement on what the Tories had planned, this new bill will massively expand the scope of automated decision-making. What’s more, Labour has also resurrected one of the most controversial parts of the DPDI in the form of the public authorities (fraud, error and recovery) bill, which will force banks to spy on all their customers in the interest of tackling welfare fraud.

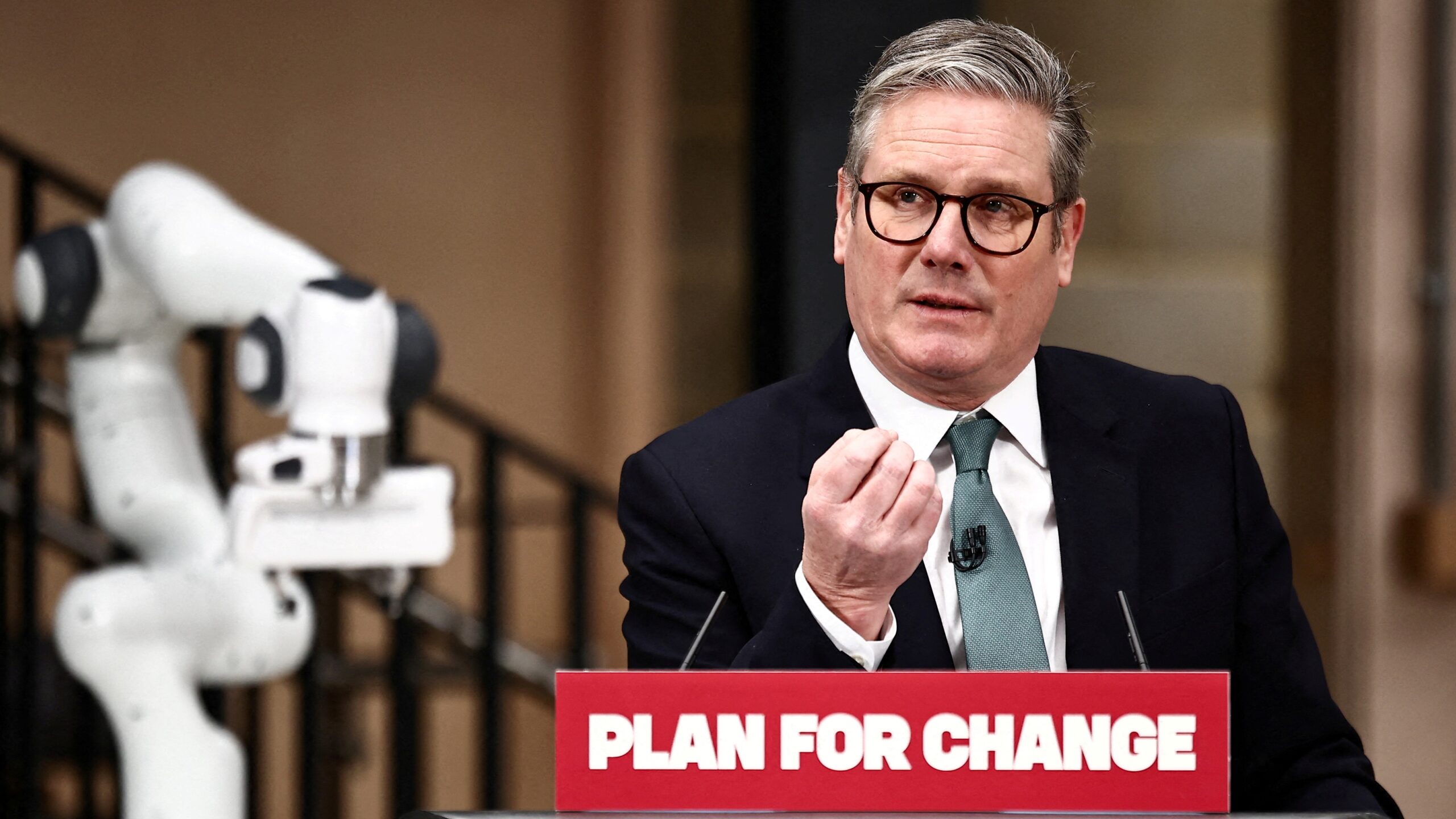

Prime minister Keir Starmer has said he wants to “mainline AI” into the veins of government. Starmer’s AI fervour is encouraged by the Tony Blair Institute, which advocated for turning the DWP into an “AI exemplar” department in a July 2024 report. Labour is opening the floodgates to not just a digitised welfare system that treats all claimants as suspects simply because they need support – but a public sector where AI tools are being used to dictate our lives in ways that we aren’t necessarily aware of.

Biased and ineffective.

In documents released under the Freedom of Information Act at the end of last year, the DWP admitted to finding bias in an AI tool used to detect fraud in universal credit (UC) claims.

The machine learning tool – which focuses on claims for cash advances to cover the five-week waiting period while a UC application is processed – had been assessed for fairness by the DWP several times since at least July 2023, the documents revealed. Each analysis found that the algorithm and intervention process are more likely to incorrectly flag claimants with certain protected characteristics, to an extent researchers considered “statistically significant”. Essentially, the AI incorrectly assumed that some people were more likely to commit fraud based on factors including their age, nationality and whether or not they were married.

What’s more, the DWP’s own reports admit that the metrics it uses to assess fairness are incomplete. It fails to test for bias towards many marginalised and discriminated against cohorts – or for bias regarding intersectional vulnerabilities.

Thanks to the Public Law Project’s tracking automated government (TAG) register, documents obtained under FOI requests and the DWP’s own accounts, we know between nine and 12 AI technologies are currently at work for the DWP – including the one used to assess universal credit advance claims. More are in the pipeline.

In 2023, the government launched an algorithmic transparency record to provide clear information about the algorithmic tools public sector organisations use in decision-making.

At the time of writing, the DWP has only listed one AI tool in the algorithmic transparency record despite disclosure being a requirement for over a year. The single listed tool is called “online medical matching”. The DWP has said it uses the tool in processing claims for employment and support allowance (ESA) – the main health-related benefit claimed by approximately 1.5 million people if their capability for work is limited by a condition or disability.

The AI matching tool is supplied by global IT giant Accenture, a multinational that originated in the US but is headquartered in Ireland, allegedly to avoid paying higher rates of tax. Accenture has been embroiled in a number of controversies over the past 20 years, withdrawing from its NHS IT overhaul contract in 2006 due to disputes over delays and cost overruns.

The DWP says online medical matching works like this: when a claimant shares their symptoms or diagnosis as part of their ESA claim, AI matches the condition to those listed in the DWP’s incapacity reference guide. The closest match is used to register the claim, which is then reviewed by a human agent who decides whether ESA should be awarded.

Between 2020 and 2024, the initial iteration of the AI tool was used covertly by the DWP and was highly unreliable. It only correctly matched conditions 35% of the time. By the DWP’s own admission, this meant “chronic fatigue was translated into chronic renal failure or partially amputation of foot was translated into partially sighted”.

The DWP claims that switching to an updated large language model has increased accuracy to 87%. However, this updated score is based on a small sample size of just 360 cases, casting doubt on how accurate it actually is. Since July 2020, online medical matching has processed over 780,000 cases.

AI guinea pigs.

It’s become clear that the Labour government is betting the house on AI as a magic formula for bolstering growth. In January, it published a 50-point AI opportunities action plan – essentially a notice of intent to procure services for AI development, allowing the government to “rapidly test, build or buy tools”.

Disability campaigners have warned that benefits claimants are merely guinea pigs in the government’s public sector AI plan – without their consent or even their awareness. The DWP has been using machine learning tools since at least 2020, but there is a serious lack of transparency around the identity of all AI tools used, their efficacy and what – if any – safeguards have been put in place to prevent bias or mitigate the impact of real-world harm.

Proof of concept pilots are slippery things. We know that they’re happening, but we don’t know all the tools involved, how many populations they are being tested on or in which geographic areas. The algorithmic transparency register doesn’t require them to be published – and formal exemptions can be applied for to avoid publication.

According to the Guardian, DWP officials told tech companies last August that “approximately 9 POCs [proof of concepts] have so far been completed” and “one POC has gone live, one is in the process of going live”.

Rick Burgess, from Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People, says that with POCs one of two things tend to happen. “If they’re catastrophic and don’t work, the DWP just quietly disappears them, and quite often, no one even knew it happened. NDAs are quite common for the people working on them. And if they like it, it then starts to roll out.”

One piloted tool, called ‘white mail’ which ‘reads’ benefit claimants’ correspondence and supposedly prioritises the most vulnerable cases (implicitly deprioritising others), has come under fire for its handling of sensitive personal data – including national insurance numbers, birth dates, claim details, health information, bank account details, racial and sexual profiles and details on children’s birth dates and special needs.

Documents released to the Guardian under the Freedom of Information Act show that benefit claimants have no idea it’s being used on them because the DWP has decided they “do not need to know about their involvement in the initiative”.

Another two technologies have been quietly dropped – A-cubed, which was supposed to help DWP staff get jobseekers into work, and Aigent, intended to accelerate personal independence payments (PIP).

Burgess argues that while biased and ineffective AI is being used on disabled people first, we should all be afraid – as well as outraged. He believes the use of AI tools in areas like welfare is a precursor to them being rolled out more widely in the public sector – something that affects the lives of every single person in the UK, whether they receive benefits or not.

“The populations they test these technologies on are generally asylum seekers and people on benefits because they consider them to be relatively powerless and unsympathetic as a political group. So if they victimise us or make terrible mistakes, it’s not a problem for them,” Burgess told Novara Media.

The Department of Work and Pensions responded to a request for comment after this piece had been published. It said: “The use of AI will help us fulfil our obligation to protect public funds and is being developed within a robust governance and ethnical [sic] framework. We do not use AI to replace human judgement to determine or deny a payment to a claimant.”

Harriet Williamson is a commissioning editor and reporter for Novara Media.