Here’s How Reform Will Betray Its Voters

No ads, no distractions – just quality journalism. Our supporters make this possible. Join them today and give one hour’s wage per month to back independent media.

On the eve of the local elections, Reform leader Nigel Farage gave an interview to Sky’s Beth Rigby. What, she asked him, is the biggest risk in success at the polls? Farage’s answer was spot on: succeeding then not delivering.

Reform did succeed, of course. Last Thursday, the party took one parliamentary constituency and two mayoralities, while gaining overall control of ten councils and 677 council seats – 41% of the total up for grabs (though one new councillor has already been suspended). That’s an unprecedented performance, representing a breach of, if not yet an end to, the two party system that’s strangled political progress in this country for decades.

Not, to be clear, that I think Reform’s wins are progress. They aren’t. Power for the party means its grim commitment to dehumanising immigrants and refugees will further embolden racists online and off; the poorly-funded councils it now controls may well see DOGE-style cuts to services; and a surge of new councillors with radical axes to grind will probably slow the delivery of what remains.

Farage was right to identify delivery as a threat. You can’t last long running on the promise of change without quickly making sure your voters feel it positively – just look at Keir Starmer’s Labour party. In many parts of England, Reform promised big change on immigration, a national rather than local policy. On Sunday, one new Reform councillor in Kent told the BBC: “Somebody stopped me today and said, ‘When are you going to stop the boats then?’”. It’s bins, not boats, that local councils control.

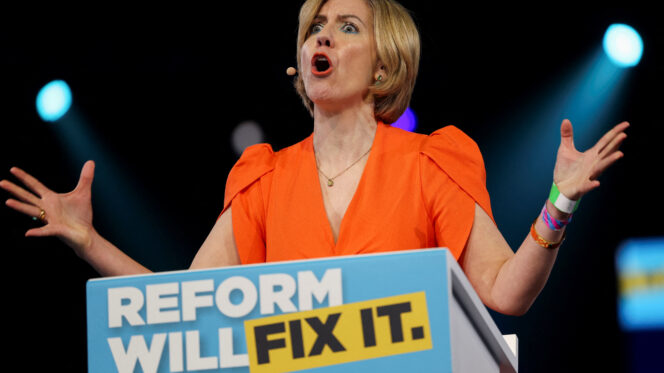

That gap between what was promised and what can be done indicates a brewing issue for Reform. Its more radical and loyal base will be highly sensitive to signs of the party going mainstream. Those who voted or campaigned for a disruptive, anti-establishment political force – one that will throw out the law, overrule the courts, punish asylum seekers and impose a tighter social order – will be on the lookout for backsliding. But to achieve the party’s national aims (Farage as future prime minister was mentioned in the victory speeches of Reform’s new MP for Runcorn and Helsby Sarah Pochin and mayor of Lincolnshire Andrea Jenkyns), mainstream is where it will have to go.

Farage gets this. That’s why he’s setting out a broader populism. He knows that to win a larger base, he’s got to reject Tommy Robinson, expel MP Rupert Lowe and fight unpopular policies pushed by the larger parties that impact the country’s poorest. He understands that his path to power lies in exploiting anxieties about migration while not indulging every sadistic whim that accompanies them. His strategy will be to tempt fed-up voters from nearer the centre while activating a sizeable chunk of the electorate who don’t vote. In the last election, as with almost all others, the cost of living was the most important issue for every segment of the British electorate, no matter how you sliced it. In these local elections, it was Labour’s end to the winter fuel allowance that motivated many voters to turn to Reform.

But economic policies are not Reform’s strong point. At last year’s general election, the party promised to radically shrink the state to fund tax cuts and to open Britain wider than ever for business. So, Thatcherism. That’s hardly radical change; her ideology has to some extent shaped the economic policies of every government that followed her. Think how often you still hear that a national economy is like a household budget, that there’s no magic money tree, that the state’s credit card is maxed-out.

Farage, however, is nothing if not skilled at sniffing out the mood. Before these local elections, his economic agenda swung left as he championed state ownership of steel and water, praised the unions, and preached protectionism for British businesses and workers. The popularity of these ideas will be no surprise to anyone on the left. But the long arc of Farage’s political career suggests his heart – not to mention those of his donors and diehards – isn’t really in them.

Either way, Britain’s austerity-induced malaise means that betrayal will be the price Reform voters pay as the party grows. First it’ll betray its older, radical base as it softens its approach to broaden its appeal. Then it’ll betray its newer, broader base when its baseline economic commitments collapse either into bog-standard Conservatism or emptiness, leaving the party unable to address the deep difficulties we face.

We’re steadily getting poorer, less equal and more sick. A catastrophic social care crisis is already hitting us, made invisible by the invisibility of those it most affects. Good, affordable housing has all but disappeared, and real jobs with both dignity and prospects are vanishing from our towns and regions. People across the country feel not just the malaise, but also the suffocating sense of helplessness it induces.

Depressing, right? But here’s the Reform silver-lining. People don’t like to feel helpless. People don’t want to be governed by their circumstances. What the local elections show is that they’ll move in all kinds of ways electorally to change the conditions imposed on them. And that when they do, they can break through political mono-culture. This has been proved. Electorally, Reform has pushed open a door. But they can’t be the only ones to go through it.

Green party deputy-leader Zack Polanski has announced his bid for leadership of the party, pitching a broader leftwing position, regional focus, and a charismatic, media-savvy approach. Former North of Tyne mayor Jamie Driscoll and Starmer-opponent Andrew Feinstein appear to have soft-soft-launched some kind of leftwing project. More contenders to fill the progressive space vacated by Labour may emerge. If they do, Reform’s victories, as well as its evident cracks, have given all of them a roadmap too.

Ruthlessly crucify your opponents where they’re weak – the promises they’ve broken and the anger they’ve sown. Run fallible, likeable and local human beings over autopilot technocrats. Make the case for a radical economics fit for the future, and pledge the policies people already want. Offer solutions to the issues that voters say impact them the most – they don’t have to be the solutions people say they want, but they do have to address the neglect they feel.

And build a media. Reform and GB News are two sides of the same coin, with the channel allowing the party to build consensus around migration (its only real political idea), grow the familiarity of its key players, and bypass mainstream media hostility. The British left owns hardly any media space, and leftwing figures remain strangely wary of what does exist. That will have to change.

But change is in the air, and it’s good. The local elections show that Britain is electric with desire for a new politics, thrumming with the energy to throw out the old and bring in the new. Reform’s advantage in these elections wasn’t its policies or its people. It wasn’t its strategy or style. It was that that energy is real and growing. And Reform – but only Reform – was there, ready to channel it.

Steven Methven is the editor of Novara Live, Novara Media’s nightly news and politics YouTube show.