Foreign Office Bosses Have a Suggestion for Staff With Gaza Conscience: Resign

Over 300 Foreign Office officials who collectively raised concerns about the government’s handling of the Gaza genocide have been slapped down by their Whitehall superiors in a letter described by a former senior diplomat as “shameful”.

Sir Oliver Robbins and Nick Dyer, the two most senior civil servants in the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), reminded a group of officials that while they welcomed “healthy challenge”, there were other “mechanisms available to those who are uncomfortable” with policy besides applying collective pressure – including resignation.

In mid-May, officials wrote to foreign secretary David Lammy urging the government to end its collaboration with Israel and comply with international law.

In their response, seen exclusively by Novara Media and published in full below, Robbins and Dyer suggested that employees worried that the government may be enabling war crimes speak to their line managers, vent to a staff counsellor or resign, the last of which they described as “an honourable course”.

A former senior British diplomat described Robbins and Dyer’s letter to Novara Media as “shameful” and “a sneering fob off” to staff acting on “deep personal conscience”. They called on the House of Commons foreign affairs committee to investigate the exchange.

Zarah Sultana, an MP currently suspended from the Labour whip for opposing the two-child benefit cap, told Novara Media: “This is what happens when a government enables genocide: it silences its own workers, censors questions and dares them to quit rather than change course.”

In a statement, an FCDO spokesperson told Novara Media: “It is the job of civil servants to deliver on the policies of the government of the day and to provide professional, impartial advice as set out in the civil service code. There are systems in place which allow them to raise concerns if they have them.”

The letter exchange exposes the long-running battle within the civil service over Gaza, one that has only occasionally spilled into the open.

‘The erosion of global norms.’

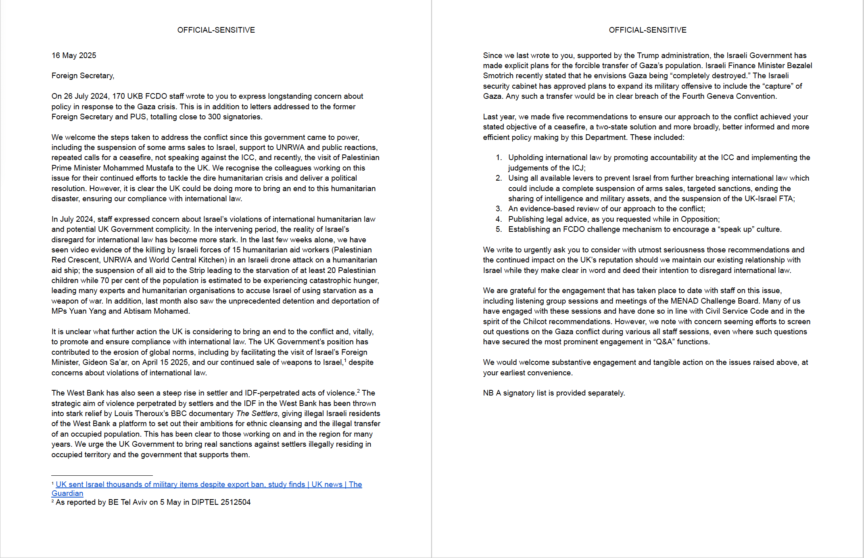

In their letter to Lammy on 16 May, 310 FCDO staff reiterated their “longstanding concern” over the UK’s Gaza policy. “It is clear the UK could be doing more to bring an end to this humanitarian disaster,” they wrote – and could even be abetting it.

The group acknowledged that despite some steps in a positive direction – including the Palestinian prime minister Mohammad Mustafa’s recent visit to the UK, the partial suspension of arms sales to Israel and the UK’s refusal to critique the International Criminal Court or UNRWA, as the US has done – the UK’s contribution to the conflict was largely negative.

“The UK government’s position has contributed to the erosion of global norms,” the group wrote, citing the government’s continued sale of weapons to the country despite a supposed export ban, and its recent welcoming of Israeli foreign minister Gideon Sa’ar.

In a statement to Novara Media, an FCDO spokesperson pushed back on its staff’s claim that the government wasn’t sufficiently restraining its ally: “One of this government’s first acts was to review and suspend export licences that could be used by the Israel Defense Forces in Gaza. We have continued to call for the Israeli government to stop its military operations there and immediately allow humanitarian aid to enter.”

Yet these measures barely scratch the surface of FCDO staff proposals, first made in another letter sent almost a year ago, “to ensure our approach to the conflict achieved your stated objective of a ceasefire [and] a two-state solution.”

These included implementing the judgements of the International Court of Justice; preventing Israel from breaking international law, including by completely suspending arms sales, introducing targeted sanctions, stopping the sharing of intelligence and military equipment and suspending the UK-Israel free trade agreement (the UK government announced in mid-May that it was suspending trade talks with Israel on a new agreement, though the current one remains in place); conducting a review of the department’s approach to the conflict; publishing advice received from civil service lawyers on the legality of supplying weapons to Israel, something Lammy lobbied his predecessor David Cameron to do; and establishing better mechanisms for civil servants to challenge decision-making.

None of the five recommendations has been implemented. “We write to urgently ask you to consider with utmost seriousness those recommendations,” the staff group wrote in its recent letter, “and the continued impact on the UK’s reputation should we maintain our existing relationship with Israel while they make clear in word and deed their intention to disregard international law.”

“The distasteful irony of it is that the signatories are fully defending international law and the government’s stated policy, but their bosses are not,” said the former senior British diplomat. “The reply seems to lack any sense of history, or the diplomatic significance of Israel’s disgrace.”

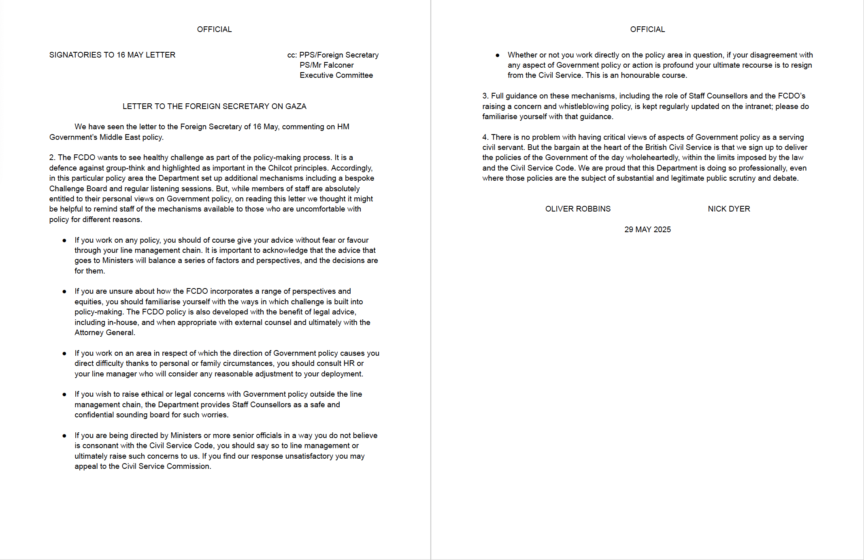

Ignoring the substantive points and recommendations of the 16 May letter, Robbins and Dyer offered a “helpful” list of actions that “uncomfortable” officials can take.

Fran Heathcote is general secretary of the Public and Commercial Services (PCS) union, which represents around 190,000 civil servants. “The response from Oliver Robbins and Nick Dyer to the concerns of staff in FCDO is consistent with the attitude displayed by civil service management [throughout the Gaza war], in that it is hopelessly inadequate,” she said in a statement to Novara Media.

According to one official who spoke to Novara Media, it is also consistent with a broader pattern of evasion and outright censorship on Gaza.

‘Fear rules everything.’

Over the 20 months since October 2023, a rift has emerged within the intensely hierarchical FCDO between junior officials (known as delegated grades), hundreds of whom have expressed dissatisfaction internally over the government’s handling of Gaza and Israel, and senior civil servants who have sought to muffle dissent, largely successfully.

One mid-ranking official in the Middle East and North African team spoke to Novara Media on condition of anonymity (in 2015, the civil service banned officials from speaking to journalists without ministerial permission). They told Novara Media that soon after the Hamas attack, they joined a WhatsApp group with around 30 junior officials in the department disturbed by Israel’s response and the government’s role in it. They added that many senior civil servants gave the impression to juniors that they should “hold your nose and just do it”, executing ministers’ decisions as much as they might object to them.

The official told Novara Media they sensed this discontent extended beyond the WhatsApp group and all the way up to senior civil servants, whom they believed were outspoken in their criticisms of Israel amongst themselves. But due to the “paternalistic” approach they claim senior civil servants take to delegated grades, and with virtually no open conversations about Gaza within the department, there was little way of knowing. “Fear rules everything in the Foreign Office,” they said. “I’m sure there are many groups like mine, which are disparate, closed, and don’t know each other exists. … I’m amazed this stuff isn’t being discussed in the corridor.”

Soon after 7 October, noting growing unease within the department, FCDO leaders organised three “challenge boards” – including on Iran and Gaza – where 15-20 members of staff with relevant expertise convened to critique government policy, their thoughts recorded anonymously and with no clear outcome. Management also organised around five “listening circles” about Gaza akin to those that had been held after the Black Lives Matter uprising of 2020. There, officials usually confined to strict hierarchies were invited to share their thoughts openly with senior civil servants – though with tight restrictions.

According to a report in Declassified UK, at one such meeting last year between FCDO officials and the department’s political director, Christian Turner, note-taking was forbidden – a highly unusual prescription for the forensically paper-trailed civil service. “Leadership in FCDO is extremely paranoid and scared stiff about leaks” about Gaza policy, said the FCDO official, adding that leaders had quickly “gone underground”.

One way this mentality expressed itself was through the creation of deliberately opaque team structures and communication barriers. “The IHL [international humanitarian law] team, the guys who are doing legal assessment, have been compartmentalised,” the FCDO official said. “Nobody can speak to them, nobody knows who they are.”

Elsewhere, the silencing was more explicit. In their letter, FCDO staff allege that “seeming efforts” were made to “screen out questions on the Gaza conflict” during all staff sessions at which ministers or senior officials were present, even when those questions had “secured the most prominent engagement in Q&A functions”. “Lammy … views any dissent on this subject as a pain in the arse,” the FCDO official said.

Robbins and Dyer do not address staff’s accusation of censorship in their letter, instead hinting that staff may be “unsure about how the FCDO incorporates a range of perspectives and equities,” and that “you should familiarise yourself with the ways in which challenge is built into policy-making.”

‘An HR car crash.’

Besides participating in listening circles or challenge boards, Robbins and Dyer suggested several courses of action to staff unhappy with the government’s work on Gaza and their own involvement in it.

Among them are that civil servants “give your advice without fear or favour through your line management chain”, acknowledging that “the decisions are for [ministers]”. If staff face “direct difficulty” working on Gaza “thanks to personal or family circumstances”, they “should consult HR or your line manager”. Ethical concerns can be raised with “staff counsellors”, “a safe and confidential sounding board for such worries”. And if officials feel they are being asked to contravene the civil service code, they “should say so to line management or ultimately raise such concerns to us”.

Finally, “if your disagreement with any aspect of government policy or action is profound”, Robbins and Dyer write, “your ultimate recourse is to resign from the civil service”.

“This is an HR car crash,” said the former senior UK diplomat. “Their reply is utterly offensive to decent people – in this case hundreds of them – whose principles and motivation made them seek a career in diplomacy only to see them now disdainfully dismissed as if they are an awkward employee who needs counselling.”

They added: “This should have been a reasoned reply from the foreign secretary to what was a perfectly reasonable letter. It should not have been a sneering fob off by two permanent secretaries who will have now totally lost the confidence of the building. Their judgement is appalling, and their response is shameful. This is a matter of deep personal conscience; not an issue of conduct.”

Heathcote echoed this sentiment, describing the offer to resign as “simply reprehensible … a dereliction of duty and a startling ignorance of the provisions of the civil service code, which require all civil servants to act in accordance with the law, including international law.”

Going public.

Despite leaders’ efforts to manage internal grumblings about Gaza, some FCDO officials have felt compelled to escalate their concerns.

In July last year, 170 people wrote to the newly-appointed Lammy, and received no response. Feeling ignored by ministers, several staff have felt compelled to go public.

A few weeks later, Mark Smith, a junior British diplomat who helped to assess the legality of arms sales to Israel, resigned from the FCDO in a letter addressed to large numbers of his colleagues, expressing fears that his former department “may be complicit in war crimes”. His resignation was quickly leaked.

Smith is the only civil servant known to have resigned so publicly over Gaza – however, several are known to have left the FCDO or the civil service for similar reasons. Certainly, many officials share Smith’s concerns about their own personal liability for Israeli war crimes.

In April last year, a letter was leaked from officials at the Department for Business and Trade to department chiefs asking to stop work on Israel fearing “legal jeopardy” for enabling arms sales to Israel, particularly if Israel is subsequently found to have broken international law. Around the same time, PCS announced it was seriously considering taking legal action to force the government to allow officials to stop work supplying Israel with arms.

Officials’ fears of the personal consequences of doing such work are not unfounded. In August last year, UK campaign group Global Justice Now published legal advice indicating that civil servants and ministers could be held personally liable if Israel is subsequently found guilty of war crimes.

“Staff are understandably concerned about their own complicity in international crimes being committed in Gaza,” said Dania Abul Haj, senior legal officer at the International Centre of Justice for Palestinians, “and yet officials do not acknowledge or engage with the fact that British politicians, and indeed civil servants, may be held liable for their decisions to facilitate Israel in committing war crimes, crimes against humanity and even genocide in Gaza – both under domestic and international law.”

Robbins and Dyer concluded their letter to colleagues by stating that it was their duty to execute the government’s Gaza policy, however controversial. “The bargain at the heart of the British civil service is that we sign up to deliver the policies of the government of the day wholeheartedly … even where those policies are the subject of substantial and legitimate public scrutiny and debate.”

Speaking to Novara Media, the FCDO official felt that this “grand bargain” contradicted leaders’ stated ethos. “The culture of this grand bargain is one of ‘Officials advise, ministers decide,’ and once they’ve decided, we have to lump it … But that’s not really in the spirit of challenge,” they said.

“If you have that as your overarching kind of culture, at what point do you really challenge?”

This culture of challenge has been particularly encouraged within the civil service since the Chilcot inquiry into the Iraq war. Completed in 2016, the inquiry noted a tendency towards “groupthink” within government and an overly “can-do attitude” among military officials. Both the staff letter and Robbins and Dyer’s response refer to the “Chilcot recommendations” as integral to their thinking.

Senior officials’ rare public statements on Gaza tend to echo ministers’. In the FCDO’s 2023-2024 annual report, then-permanent under-secretary Philip Barton surveyed what he described as a “testing year”: “Russia’s illegal war against Ukraine entering its third year. Hamas’ barbaric terrorist attack on Israel and its aftermath. Sudan’s rapid descent into civil war. Humanitarian need and hunger on the rise.” When the report was published in July 2024, 38,000 Gazans were dead, half a million facing catastrophic food insecurity.

FCDO chief Robbins – a former deputy national security adviser involved in the interception of Edward Snowden’s intelligence leaks – succeeded Barton in January.

The Commons foreign affairs committee is currently conducting an inquiry into the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and has previously worked with FCDO whistleblowers. Submissions to its inquiry officially closed in December, however whistleblowers are invited to contact the committee on a rolling basis.

Rivkah Brown is a Novara Media commissioning editor and reporter.