Reform Threw the Kitchen Sink at Scottish By-Election – And Came Third

Labour limped to an unexpected victory over the SNP.

by Adam Ramsay

6 June 2025

Paywalls? Never. We think quality reporting should be free for everyone – and our supporters make that possible. Chip in today and help build people-powered media that everyone can access.

In Hamilton, South Lanarkshire on 4 June, I noticed a Labour canvasser on a doorstep. Stepping closer, I overheard the conversation: the canvassee was afraid of Reform. Formerly a Labour supporter, he’d be voting for the Scottish National Party (SNP). He believed – wrongly, it transpired – they had a better chance.

The canvasser responded that she’d “rather he didn’t vote” than vote SNP to stop Reform.

Afterwards, I approached her. “Did you really just ask that man not to vote, rather than vote SNP to stop Reform? Would you really rather have a Faragist than an SNP MSP?” – despite Reform’s racist smear campaign against Anas Sarwar. She denied it, angrily.

I knocked on the door. The man confirmed my version. In any case, he added, he would “never vote Labour again” since prime minister Keir Starmer’s “borderline racist” ‘island of strangers’ speech.

Earlier, outside Stonehouse’s polling station, I was chatting with a foursome of Reform activists from Perth – two prim Tory ladies, two long-ago Labour men – when a party alpha strutted up and started speechifying at them. The Scottish Green co-leaders Lorna Slater and Patrick Harvie had once called him racist, he boasted. “If I met them down the pub on a Saturday night,” he said, “I’d…” he punched his hand.

When I introduced myself as a journalist, he replied, “but, you’re a true believer… right?”.

These snippets suggest that the 5 June Holyrood by-election in Hamilton, Larkhall and Stonehouse was a high energy affair. But mostly, tensions were running low.

Most people I approached weren’t voting. Those who were had three motivations: general obligation, a desire to stop Reform, or a desire to support them. Many said they were still undecided. Turnout – 44% – was respectable for a by-election. Don’t mistake that for enthusiasm.

“We’ve just got to hope there are more good people than bad in Hamilton,” said one 40ish woman at a Greek takeaway. She’d voted Labour in 2024 but was going SNP because “I don’t like Labour’s position on trans rights. Are they going to have people inspecting women in the toilets?”

She’d also liked Christina McKelvie – the SNP MSP whose death prompted the by-election. That was the only positive comment anyone made all day.

Behind her in the giros queue were some sixth formers – 16 year olds can vote for MSPs and are often very engaged. But only one of them planned to. “My dad says ‘probably Labour’. So probably Labour.”

There were three notable features of this electorate. First, its liquidity – almost no one professed loyalty to one party. Twenty years ago, the vast majority of Scots were long term, often intergenerational, devotees of one team or another, with loyalties – whether Labour, Liberal or Tory – which ran through family lines and geological seams. Literally: central Scotland’s coal bed produced Labour voters, the ragged Highlands encouraged liberalism, the fertile north east and south bred wealthy Conservatives. Now, many were picking between Labour and SNP at the last minute, without much pleasure.

Second, as between changing tides, the water’s slack. There wasn’t energy. I’ve done these interviews across the UK – and the world. I felt the raw rage in Rochester and Strood as it elected UKIP’s Mark Reckless. Stonehouse wasn’t Strood. The I’m-not-interesteds shrugged rather than spat.

A couple of people were furious: “I’ll never vote Labour again because of what they’ve done with the winter fuel payment”. Both Reform voters I met raged about SNP ‘corruption’. A few people hated Reform. But, beyond activists, that was the only passion I got all day. Starmer and Swinney are both technocrats. Neither name came up once.

The third is that almost everyone was voting against something. As one man said, “they’re not proposing anything, they’re just slagging each other off.”

Labour’s victory is remarkable. But it didn’t come from hope. The win for Scottish Labour’s Davy Russell was delivered by earnest activists and MPs who, throughout the day, arrived at their town centre HQ and set off in packs, turning out voters. In 2021, they got 12,179 votes and came a distant second. Yesterday, they got 8,538, and won.

By-elections are always about who can get people to the polling station, and Scottish Labour, with 37 MPs and flush with millionaire money, has a serious machine again. I didn’t see an SNP activist all day.

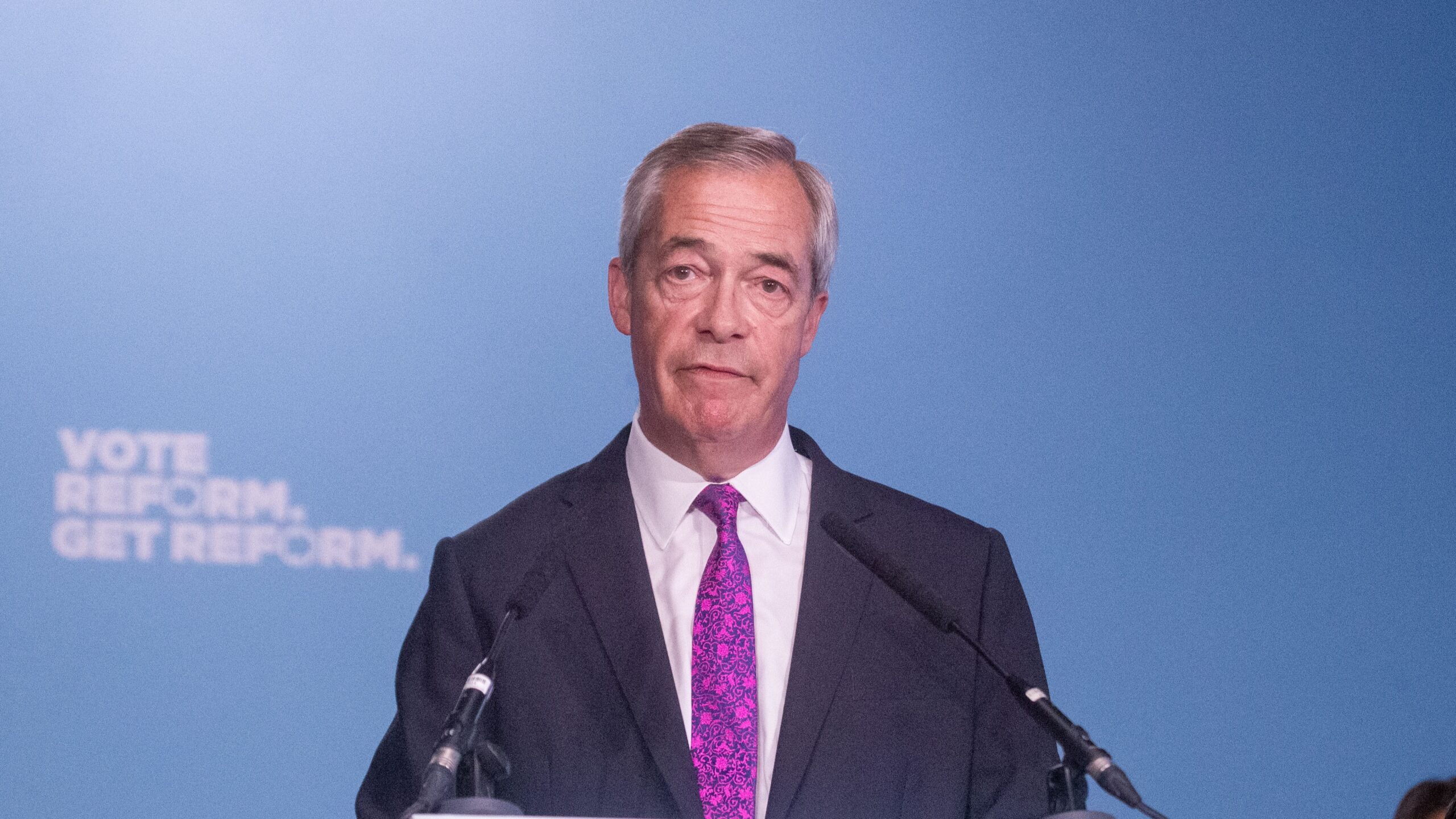

This is a constituency in former coal-mining country with Amazon-eroded town centres – a mix of struggling county town, increasingly-automated agricultural belt and more affordable commuterland for a nearby post-industrial city – which Reform would expect to take in England these days. The party threw a campaign bus, Nigel Farage and racist adverts at the seat, and came third. Holyrood’s proportional system means they will certainly get MSPs next year. But their Scottish breakthrough remains delayed.

A by-election is just a by-election. But ultimately, the problem of Scottish politics persists: no one is offering anything anyone actually likes. The main motivations for voting were negative. In the general election next year, there’s an obvious space for the left to act – an obvious opening for the Greens, perhaps. Will they take it?

Adam Ramsay is a Scottish journalist. He is currently working on his forthcoming book Abolish Westminster and has a Substack of the same name.