The Palestine Action Ban Has Had a Chilling Effect on the Press. It Must Be Overturned

A climate of fear.

by Charlotte England

22 July 2025

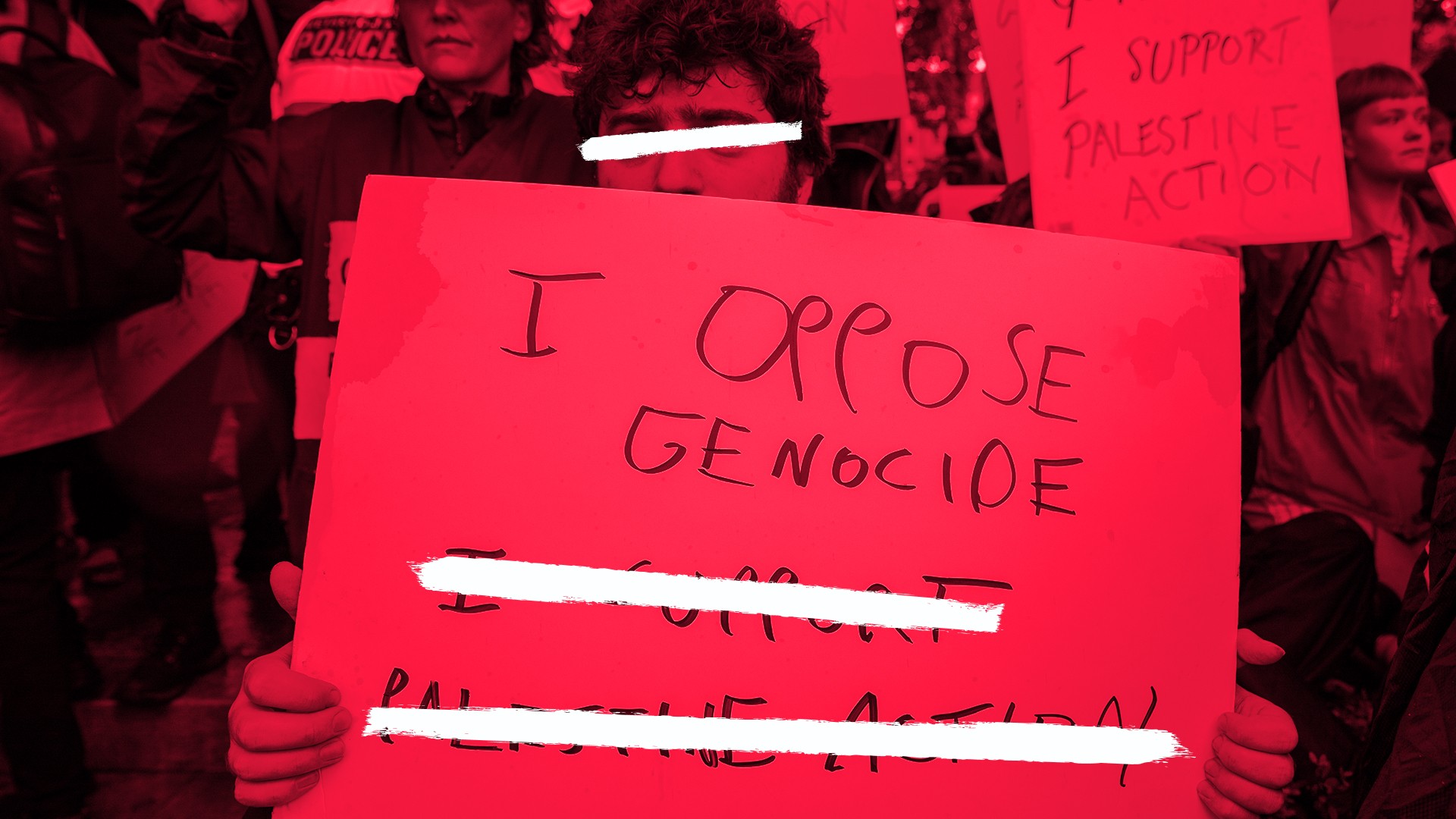

On Saturday 5 July, the day Palestine Action was proscribed as a terrorist organisation, 29 people were arrested for sitting in Parliament Square with handwritten signs that read “I oppose genocide. I support Palestine Action.” Among them was an 83-year-old priest, Sue Parfitt, who described the significance of the action – it was “testing out the law”, she told our reporter.

It was always clear to us at Novara Media that the protest would be newsworthy, whether arrests were made or not. We agreed with Parfitt: how the state responded would be telling. Either outcome would be politically significant. By not acting, the police would be showing an unwillingness to enforce the ban on day one. Making arrests, meanwhile, would illustrate the shocking reality of the new law. Dragging away old people for words written on pieces of cardboard would look draconian.

The value of covering the action, then, was clear to us. Given our audience – politically-engaged, leftwing and pro-Palestine – it would have been strange, to the point of remiss, for us to ignore it. Yet on the night before the action, we were unsure if we could go ahead.

We had a sense that the terrain was profoundly shifting. What, now, could be perceived as constituting support for a terrorist organisation? Could we publish images of the group’s signs or quote people taking part? Could we cover – and in doing so, publicise – the action at all? If we went ahead, would we be treated in the same way as rightwing media organisations, that had never interviewed Palestine Action members in the past and still – as reports emerge of more and more people starving to death – won’t explicitly say that Israel is committing a genocide in Gaza?

When, ultimately, we did decide to go ahead, journalists from much larger organisations told us they were equally confused. No official guidance was provided to the media about the implications of the new law, and no journalistic exemption was written into it. Legal experts have struggled to understand how it is likely to be applied and often can’t give clear advice, except to exercise extreme caution. In many cases, extreme caution looks like not reporting things at all.

The likelihood of being prosecuted might be relatively small. But the penalty for breaking the law is not. Our understanding is that our directors at Novara Media could be held criminally liable for any breach and sentenced to up to 14 years in prison. Meanwhile, our platforms could be deactivated.

This is the chilling context that I described to a high court judge on Monday, in a witness statement submitted in my capacity as a director of Novara Media to support a bid for a judicial review of the ban. Other journalists, too, told Justice Martin Chamberlain how Palestine Action’s proscription has had an immediate and severe impact on press freedom in the two-and-a-half short weeks since it came into effect, while other witnesses described how it has also stifled politicians and the public.

Barrister Raza Husain, acting on behalf of Palestine Action co-founder Huda Ammori, described the ban as “an authoritarian and blatant abuse of power”. What we have witnessed and experienced in reporting on the proscription so far already backs this up.

Enforcement of the ban has been alarmingly inconsistent and often heavy-handed. Justice Chamberlain heard about this at length on Monday, with Ammori’s team arguing that members of the public have “effectively been gagged” for “trying to stop violations of international law by Israel” at a time when “an entire population is being starved” in Gaza.

While some 300 people have been arrested for holding signs that explicitly state support for the group, others have held the same signs and been left alone. At least one person has been told by police that support for the Palestinian cause in general is now a terror offence, and people have been stopped for holding signs and wearing T-shirts with slogans that are similar to those used in support of the group, but should still technically be perfectly legal.

This opaque and inconsistent application of the law has created a climate of fear for the public and for the press. It makes it even more imperative that the state issue clear guidance for journalists. Yet in three weeks, we have still not been able to get information on what we are and aren’t allowed to do – and not for lack of trying.

The day before the ban came into effect, Novara Media wrote to the attorney general, Lord Richard Hermer KC, to request urgent clarification on how proscription would affect journalistic coverage of Palestine Action.

Our eight questions were straightforward enough: Could we be prosecuted for leaving material online that was legal when published but may not be now? What if this was reshared? Could criticism of proscription or arguments that Palestine Action’s protests are legitimate be construed as support and criminalised? What safeguards exist to protect journalists? Could our letter itself be interpreted as supportive and thus criminal?

We received an immediate response from the attorney general’s office – to remind us that he is a Lord and should be addressed as such. After this, we didn’t receive a meaningful response for ten days, and then it was only to bounce us to another department. The Home Office would respond in due course, a correspondence officer told us. We still haven’t heard back.

The attorney general’s office advises online that it takes up to 20 days to reply to public enquiries. But there was a reason that we asked for clarification as a matter of urgency. In the time that has elapsed without an answer to our questions, we have had to make tough decisions almost every day about the risks we are willing to take to do work that feels more imperative now than ever, without jeopardising our operations and putting our staff in danger.

A podcast that was shortlisted for a prestigious award that includes material that may now break the law. Can we refer back to it? An arrestee we interviewed gave a particularly strong defence of Palestine Action. Can we publish it? Should the words ‘I support Palestine Action’ ever go in a headline?

Terror law has been weaponised unlawfully against journalists in the past, with catastrophic consequences for their work and lives, even when ultimately they have been found to have done nothing wrong. In October 2024, journalist Asa Winstanley’s home was raided at dawn by counter-terrorism police who seized his devices. No charges were ever brought against him and in May of this year a court ruled that the raid was unlawful.

Given this precedent, it’s difficult not to worry that a counter-terrorism investigation could be launched on scarce grounds, severely impeding our operations or even shutting us down by confiscating our work devices and intimidating our journalists, irrespective of whether any actual charges could be brought against us. The application of the law in the past has demonstrably been ‘raid now, justify later’.

With this in mind, we have already put protections for our employees in place. We have instructed our staff to share their line managers’ contact details with their housemates and families, so that should anyone get arrested in the night, they can raise the alarm. Otherwise, we have continued to report on protests as usual. But there are other areas in which we have had to make troubling compromises.

Soon after Palestine Action was proscribed, we interviewed a high-profile political figure for Novara Live, our flagship YouTube show. Without prompting, he chose to make statements that may have broken the law. This would clearly have been a newsworthy story of interest to our audience: a very well-known public figure choosing to defy proscription.

If we had covered this on the show, we would have pointed out that his statements likely contravened the law and distanced ourselves from them, while clarifying for our audience the restrictions now placed on such speech. But given the climate of fear and uncertainty over the scope and application of the law, as well as the potentially catastrophic consequences of finding ourselves faced with a terrorism prosecution, we chose to cut the full section on Palestine Action from the interview. This is not a decision we would otherwise have made, but in this instance the risk of prosecution, or even merely investigation by counter-terror police, led us to censor what was clearly a newsworthy piece of journalism.

For now, it’s a waiting game: Justice Chamberlain has said he will announce whether or not he has decided to permit a judicial review on 30 July. In the meantime, the Palestine Action ban will continue to inhibit our freedom to report important truths. What we are experiencing now is unprecedented and alarming, and worse than that, it is a distraction and a drain on our resources at a moment when our focus as journalists should be on exposing how a population is being slowly and deliberately starved to death in Gaza. It must be reversed – the sooner the better.

Steven Methven contributed to this piece.

Charlotte England is a director and deputy head of articles at Novara Media.