Sudan and Palestine Are Haunted by the Same Ghost

The British empire.

by Kieran Andrieu

7 November 2025

In the spring of 2002, at the tender age of 14, I travelled to London with my mum to attend a demonstration in Hyde Park against Israel’s assault on the West Bank towns of Jenin and Nablus.

The zeitgeist back then felt particularly intent on crushing all hope of a free Palestine. The events of 9/11 had just inaugurated a new golden age of Islamophobia and militarism. Ariel Sharon, the butcher of Sabra and Shatila, had two years earlier been elected Israeli prime minister. As I stared out at several thousand people gathered on that crisp morning near Speaker’s Corner, mostly Arabs and Muslims, it was obvious Palestinians were still invisible to white people.

It’s now 2025, and while the zeitgeist has in many respects grown more demonic, it’s certainly true that something has shifted. In two decades, several thousand people on a good day protesting for a free Palestine has become several hundred thousand on a bad day. Where once only mosques and university campuses were represented on demo day, now there’s scarcely a sector of British life that doesn’t send its emissaries in one form or another. A far cry – and a cherished one.

But as our colossal injustice finally seeps into the collective consciousness, I worry about colossal injustices kept on the outside. There are good reasons why Palestine became a cause célèbre. Let’s do away with murmurings of antisemitism immediately: the west is financially, militarily, politically and culturally complicit in Israel’s annihilation of Gaza.

The displacement of Palestinians since 1948 has created a diaspora in virtually every country on earth, and Israel is unique as an ethnostate practicing apartheid against an indigenous, non-white population.

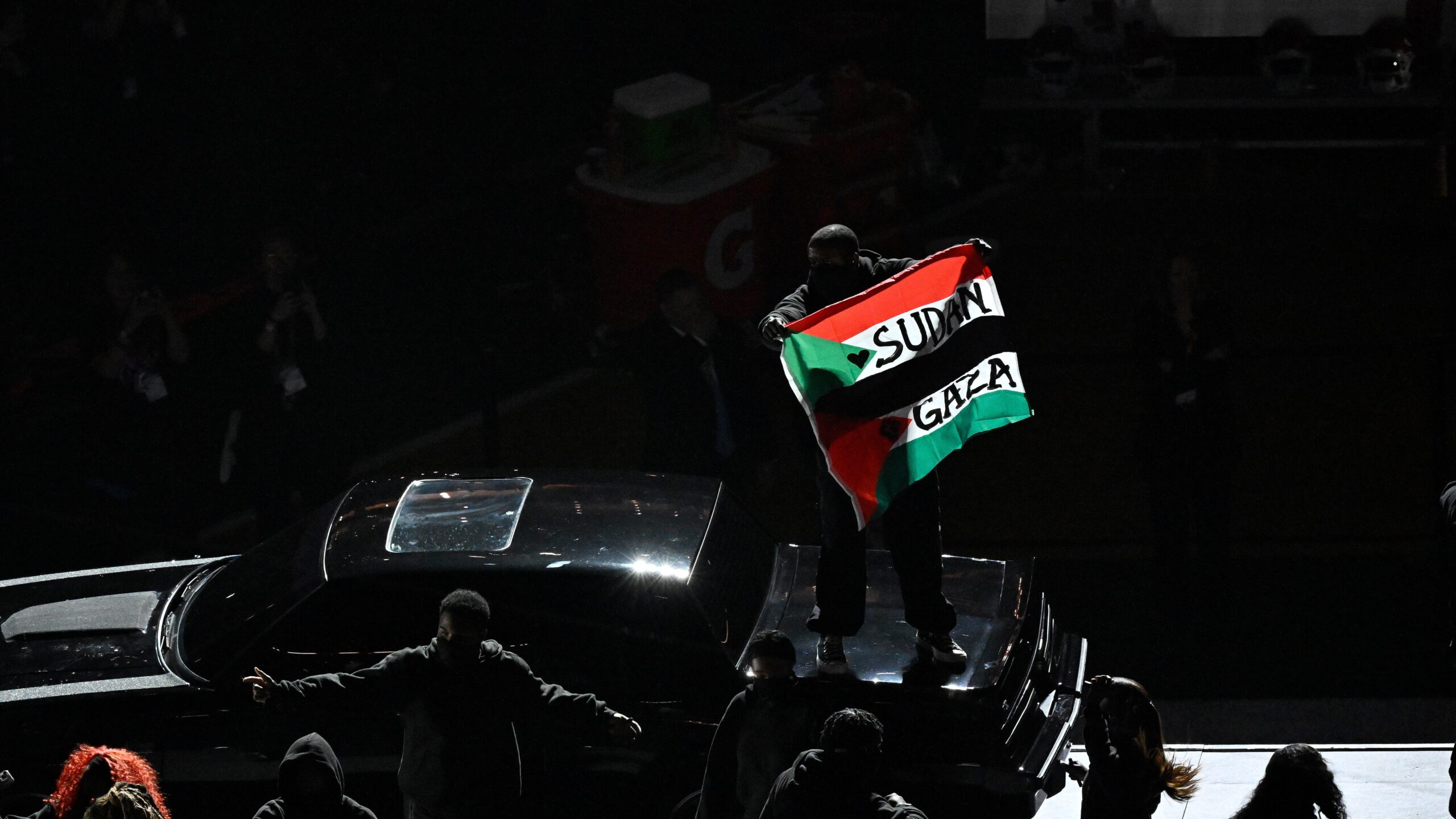

But war crimes are war crimes. Sudan keeps me up at night, not just because the Rapid Support Forces are slaughtering thousands of innocents on the United Arab Emirates’ 24-carat dime, but because – in the so-called attention economy – we Palestinians may have unwittingly kept the compassionate world’s focus elsewhere.

Sudan’s open wounds are, at their root, wounds inflicted by the British empire, just as Palestine’s are. Most people – on the political left at least – know the names Arthur James Balfour, Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot (of the Sykes-Picot Agreement) these days. Fewer people know the names Charles George Gordon and Herbert Kitchener in the context of Sudan. Well, they should – because these men and the interests they embodied are as alive in the violence that blights Sudan today as Balfour and co. are in the screams of Gaza’s children.

Gordon was once the most famous man in the British empire. His military exploits in China suppressing the Taiping Rebellion made him a matinee idol for boys primed to fantasise about ‘exotic adventures’ in the colonies. But it was in Sudan that Gordon achieved immortality.

Earlier in the 19th century, in 1820, Egypt had invaded and colonised Sudan, consummating a process of Arab dominance over the country’s black population that finds new and grotesque expression in the UAE’s proxy violence today. When the Suez Canal opened in 1869, Britain already had the largest empire in the world. Regardless, it wasn’t going to let such a critical trade route go to its rivals, and within a decade Egypt and Sudan were being ruled from London.

But in 1881, the Sudanese rebelled. Under the Islamic religious leadership of the Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad, they secured one improbable victory after another until finally, in 1884, they were marching on the capital, Khartoum. George Gordon was sent to evacuate allied Egyptians from the city ahead of its inevitable fall to the Mahdists. But once in Khartoum, Gordon disobeyed his orders, unwilling to let any part of the empire go to ‘heathens’.

The Siege of Khartoum lasted almost a year and resulted in Gordon’s death, as well as the expulsion of the British and Egyptians from Sudan. But that wasn’t the last word on the matter. Fifteen years later, seeking to recapture its imperial possession and avenge Gordon’s death, the British returned. Their leading light this time was Kitchener. Whether his name means anything to you or not, you will know his face: Kitchener is the one on those World War I posters pointing directly at you, urging you to enlist as cannon fodder.

In 1898, Kitchener was pointing in another direction. At about 6am on 2 September, he led one of the bloodiest massacres in British history – the mistitled ‘Battle’ of Omdurman. The Sudanese fought with spears, daggers, swords and a few old rifles. The British with a new technology: machine guns. By midday, 12,000 lifeless Sudanese bodies lay stacked in heaps, riddled with expanding dumdum bullets (prohibited under international law). Forty-seven British soldiers died.

Kitchener, who had been watching through binoculars from a distance, remarked that the natives appeared to receive a “good dusting”, before retiring for the day. Anglo-Egyptian ownership of Sudan was restored, and lasted until 1956.

Why is this relevant now? Because the British and their Egyptian sub-contractors kept Sudan in a deliberate state of dependency and underdevelopment, both politically and economically. A strong centralised state was denied the Sudanese – particularly fatal in a country with vast natural resources. And like every other British colony, the Sudanese economy was kept subordinate to British interests, locking them into marginal agricultural production. Perhaps most ominously, the administrators deployed divide-and-rule tactics between the north and south, invoking racial doctrines for potency.

The shift in public opinion on Palestine is a blessing – it’s the only thing that’s gone right for us so far this century. But as the genocide survivors in Gaza seem to understand a little better than some in the west, Palestine and Sudan are haunted by the same ghosts. If we are to perform an exorcism, it must include Gordon and Kitchener as prominently as it does Balfour.

Kieran Andrieu is a British-Palestinian political economist and Novara Media contributor.