Novara Media’s Best Books of 2025

Aaron, Rivkah and Steven share their picks of the year.

by Aaron Bastani, Rivkah Brown & Steven Methven

23 December 2025

From a must-read account of China’s rise to a guide to imaginative time travel – here at Novara Media, we’ve read it all. Aaron Bastani, Rivkah Brown and Steven Methven each share their top three picks of the year.

Aaron Bastani, Novara Media co-founder and contributing editor.

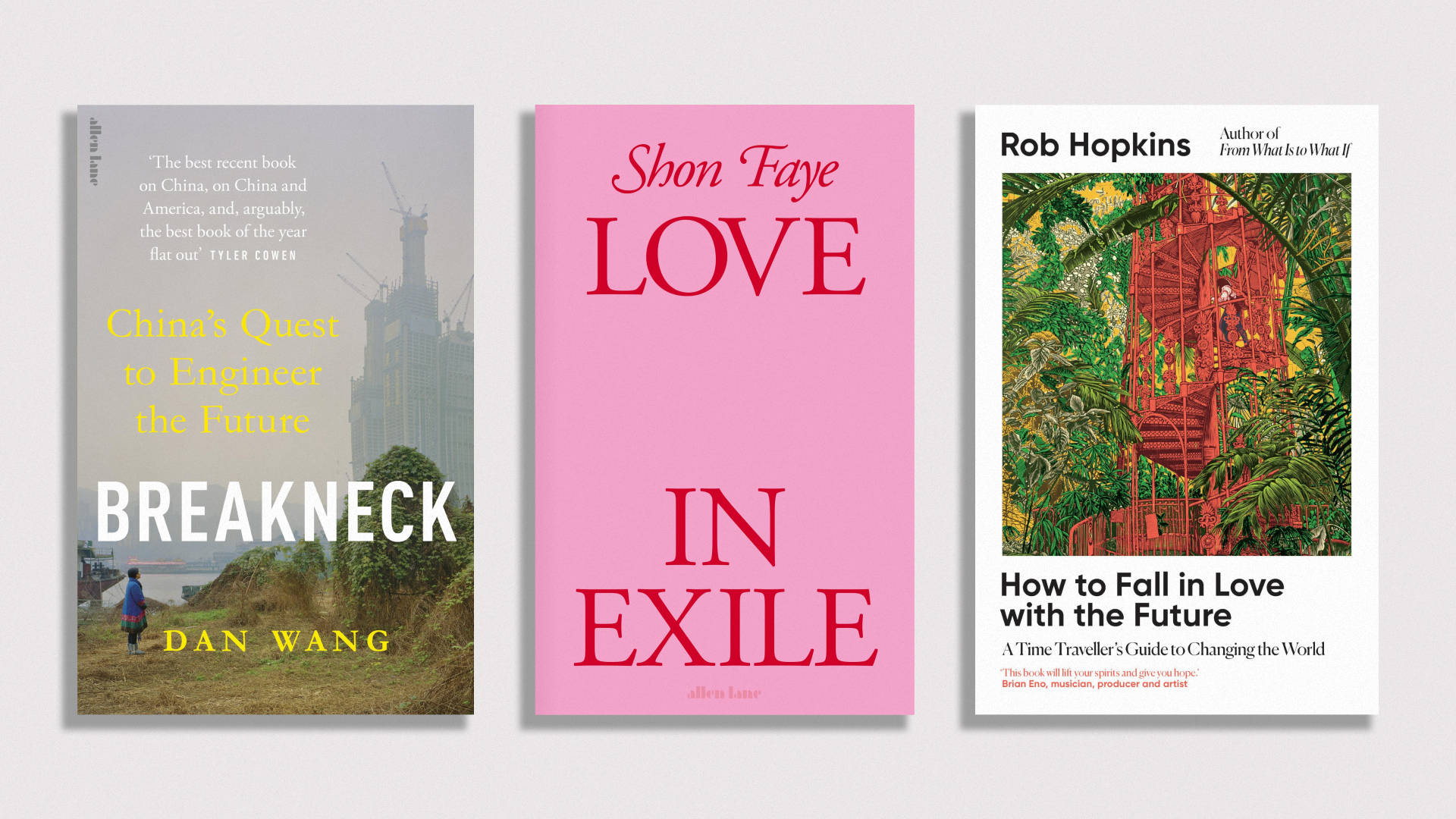

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, by Dan Wang.

The Chinese Communist Party has lifted 800 million people out of poverty over my lifetime, and is now driving the country to global leadership in a range of technologies. At the same time, it also allowed its fertility policy to be designed by a missile engineer, and maintained a zero Covid policy for inexplicably long. We have a lot to learn from China, certainly, but there are also aspects of our own societies that are precious, and worth defending.

As a Canadian of Chinese heritage, and having lived on both sides of the Pacific, Dan Wang is well-placed to be a critical friend to both Washington and Beijing. Breakneck is a must-read, not just because it offers a pithy overview of China’s rise and the politics driving its potential eclipse of the US, but for revealing how that same system led to rampant dysfunction.

Annihilation, by Michel Houellebecq.

With elections for the French presidency in 2027, the campaign for the Élysée Palace will heat up over the next 12 months. Already Jordan Bardella, the preferred candidate of the ultra-nationalist National Rally, has a healthy lead over all of his likely rivals, and victory for the party would be a breakthrough for both it and the far-right across Europe.

With that possibility ahead of us, who better to read than Michel Houellebecq? One of the continent’s most influential novelists, and the leading thinker of the ‘culturally pessimistic’ French right, Annihilation initially seems to revolve around politically motivated terror attacks. But it soon becomes apparent that the novel, while replete with Houellebecq’s usual themes of demographic ‘anxiety’, cultural decline and moral uncertainty, is more subtle.

Personally I agree that Europe is in decline – albeit for different reasons. But this conclusion is all the sharper after reading someone like Houellebecq.

Perfection, by Vincenzo Latronico.

115 pages of, well, perfection. Vincenzo Latronico’s novel is absolutely everywhere right now, but don’t mistake its commercial success for prosaic mediocrity or a thinness of ideas. As Europe’s millennials edge into their 40s, Perfection is the owl of Minerva spreading its wings on their collective youth. Only now do we truly see ourselves – and Latronico’s is a splendid mirror.

The story focuses on Tom and Anna, a millennial couple living in Berlin, who embody many of the clichés about their generation. Knowledge workers who work as freelance designers, their lives are defined by tasteful hedonism, photogenic plants and Instagram-friendly eateries. The author is merciless in documenting the idiosyncrasies of this demographic, yet he does so without ever lapsing into spite or ridicule. A brilliant novel on the almost two decades in which my generation became adults – while often failing to. Buy this for the geriatric millennial in your life.

Rivkah Brown, Novara Media commissioning editor and reporter.

Representations of the Intellectual (forthcoming), by Edward Said.

Rarely have I felt the absence of Edward Said, who died in 2003, as acutely as I have during the Gaza genocide. As thousands of words worth of prevarication and both-sidesism poured from the pens of Zadie Smith and even, at one point, Judith Butler, I’ve imagined the clarity with which the Palestinian-American scholar would have described our horrifying present.

It seems pointed that Fitzcarraldo Editions has chosen this moment to compile Said’s 1993 Reith Lectures. The six lectures examine the role of the intellectual in public life, resisting the notion that the intellectual must represent a group. Instead, Said argues that the intellectual’s lifeblood is their exilic non-affiliation, their loyalty being solely to their ideas.

When Said delivered his lectures, there was such a thing as a “public intellectual”. These days, the “intellectuals” who enjoy the kinds of intellectual preeminence and concomitant BBC airtime that Said did – people like Matthew Goodwin or Douglas Murray – are fascist-aligned pseudo-academics, while the people who deserve it are relegated to small magazines and the depths of YouTube. Meanwhile, the BBC is censoring its Reith Lectures following legal threats from the US president. Perhaps it’s best that Said isn’t around to see how much worse things have got.

Run Zohran Run! Inside Zohran Mamdani’s Sensational Campaign to Become New York City’s First Democratic Socialist Mayor, by Theodore Hamm.

I read everything there was to read about Zohran Mamdani in the run-up to the mayoral election. What was obvious was that most publications fixated on his identity, whether (in flattering pieces) his superwatt charisma or (in hostile ones) his Muslim identity. While I won’t say I was entirely unmoved by this cult of personality – I recently gave a picture of his wife, Rama Duwaji, as a reference to my hairdresser – I craved coverage that looked beyond the candidate to the campaign and its mechanics. How did Mamdani put together this stunning win, and how could it be replicated?

With meticulous detail and clearly a good amount of access to Mamdani’s cadre, Theodore Hamm recounts how Mamdani grew a universal platform out of the particularities of his identity, running a South Asian community-focused “roti and roses” campaign for city assemblyman in 2020 that teed up his affordability-focused mayoral run. Though clearly written in some haste – OR Books managed to rush out press copies of Run Zohran Run! in time for election day – Hamm’s first draft of history is the fullest and most forensic of any I’ve read, and I’ve read them all.

Love in Exile, by Shon Faye.

I listen to very few audiobooks – mostly because what could be more embarrassing than being T-boned by a lorry on my bike because I was engrossed in Britney Spears’s tell-all memoir The Woman In Me? – but I devoured this one over a few heady days in spring. It was not what I expected, which I loved. Unlike many non-fiction authors these days, who proceed ploddingly through a series of ideas mostly spelled out by their book’s title, Shon Faye takes a series of unlikely turns.

Love in Exile starts with the same premise as her last book, The Trans Issue – namely, the nature of trans experience, trans womanhood in particular – wending Christ-like through the wilderness of Faye’s relational and religious lives, reaching a ground-shaking apotheosis involving a French Carmelite nun. It would’ve been much easier for Faye to abandon Catholicism, I would’ve thought. As someone who’s become more religious in adulthood, I admire that she’s held fast to her faith, taking what is useful and discarding what isn’t. Perhaps, like Said, Faye has discovered that exile has its upside.

Steven Methven, editor of Novara Live.

The Fraud: Keir Starmer, Morgan McSweeney, and the Crisis of British Democracy, by Paul Holden.

It’s been a difficult few months for Keir Starmer, with the sense that his premiership is not long for this world growing week by week. If that’s right, then investigative journalist Paul Holden’s forensic examination of the apparently endless machinations that aimed both to bring down Jeremy Corbyn and to install the paper man who currently occupies Downing Street is especially revealing. First, of the single-minded sectarian pursuit of power allegedly embodied by Morgan McSweeney, Starmer’s right-hand man and the former head of Labour-right think tank Labour Together. But second, of the utter waste of political energy it appears ultimately to have involved. For, besides what appears to be a one-off electoral success, what did all the maneuvering achieve? Having changed very little for the majority of Britons in Labour’s first 18 months, the electorate doesn’t trust the party – perhaps quite sensibly, given Holden’s account. And after abandoning its left flank, it has few ideas and no resources to tackle a rising far right.

If you’re interested in how a certain kind of power actually works – and ultimately, also, how it really doesn’t – The Fraud is for you.

How to Fall in Love with the Future: A Time Traveller’s Guide to Changing the World, by Rob Hopkins.

On Novara Live, we’re often asked for more coverage of the climate emergency. Then, when we do it, our viewers engage much less. My theory: nobody likes to feel helpless, but there’s little else to feel when confronted by the enormity of the crisis.

In How to Fall in Love with the Future, Rob Hopkins tries to give an antidote to that paralysis, encouraging us to build “memories” of the concrete and positive futures we might jointly work towards. His technique? A kind of imaginative time travel, in which we allow ourselves to encounter those diverse futures where we’ve already resolved the crisis.

I’m not an especially whimsical person; I was convinced Hopkins’ time travelling frame would put me off. It didn’t, though, with Hopkins slowly affirming that the creative and practical possibilities for resolution lie both within and all around us. In fact, deploying the imagination positively in this emergency makes obvious sense. After all, no great human endeavour – and reducing climate change, if we can pull it off, may be our greatest yet – has ever been successful without a common, practical and compelling vision to guide us.

Orbital, by Samantha Harvey.

I went off contemporary literary fiction for a while, repelled by a seemingly endless fashion for sparse text and self-involved first-person narrators. Then came Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, the deserved winner of 2024’s Booker prize. Written in language of extraordinary poetic beauty, and humming with the mechanical rhythm of the international space station that is its setting, it tracks six astronauts as they orbit the earth in a single day – which is also 16 revolutions long.

I’ll be honest: I’m an eternal optimist about humanity, constantly struck by our species’ uniqueness and beauty, even when we’re completely horrific. This novel exudes that pro-human sentiment. It explores our fragility and strength, our tininess and vastness, both in its vision of our earth from the point of view of infinite darkness, and in its loving portrait of the complexity of each and all of us – represented by six people doing something both banal and extraordinary, together. There’s a message of hope there, and of awe – not declared, but displayed by the human cooperation, even on the very brink of the void, that is its theme.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.

Rivkah Brown is a Novara Media commissioning editor and reporter.

Steven Methven is the editor of Novara Live, Novara Media’s nightly news and politics YouTube show.