4,000 People Tried to March From Egypt to Gaza. It Was Egypt, Not Israel, That Stopped Them

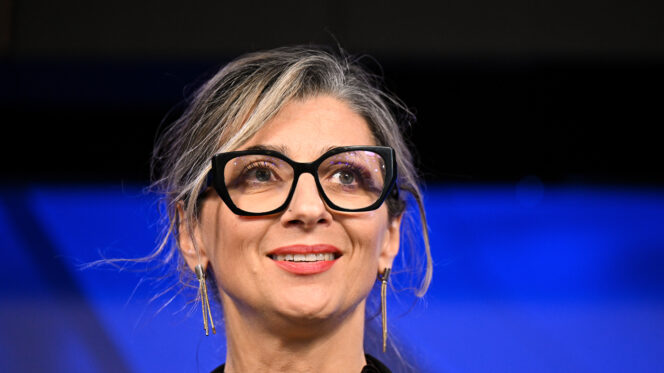

Lien Arits stepped off a plane in Cairo on a sweltering June evening. The Belgian politician wore heels and make-up at border control to avoid looking like an activist. It was a sensible precaution: the previous day, 40 members of the Dutch delegation to the Global March to Gaza had been denied entry to Egypt.

Arits was travelling to the action with three fellow members of the Belgian Green party – but to avoid being identified as a group, they agreed to act like strangers. No talking at the airport; no eye contact on the plane.

Weeks earlier, Arits and over 4,000 others from more than 80 countries had signed up for the march, which planned to take participants just 30 miles from El Arish to Rafah over three days between 15 and 19 June.

The plan was simple. Buses would take participants roughly 200 miles east from Cairo to El Arish, in the Sinai. From there, they would march to Rafah over three days. Trucks carrying food and tents would follow alongside. Each night, a new camp would be set up for marchers. Participants were instructed to bring 876 Egyptian pounds (about £13) per day to cover costs.

The organisers knew the Sinai, the mountainous region in Egypt that borders Israel, is hostile terrain, both geographically and politically. Several states, including the UK, advise against travelling to the area, which is riddled with Egyptian army checkpoints due to ongoing insurgent activity, most of which began in 2011, during the Egyptian revolution. In 2023, President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi declared the terrorism threat over. But since then, clashes have continued between armed groups and Israeli soldiers, between those groups and Egyptian authorities, and, at times, have spilled out to affect civilians. When I asked one of the Dutch march organisers whether he had considered the safety risks, he told me he doubted such a large group would be seen as a target.

Much like the activists of the Gaza Freedom Flotilla, most of the march participants never expected to reach Gaza, but rather to raise awareness of the blockade and Egypt’s role in it. “I’m not naïve,” Arits told me. “What’s naïve is thinking Netanyahu will end his war crimes without sanctions or an arms embargo. We’re doing what politicians won’t.”

Many of the people joining the march I met through Signal groups. Others I ran into at El Horreya, a smoky bar in downtown Cairo, one of the few places in the city that still serves beer. It is a regular haunt for Egyptian intellectuals, and that week had become a gathering point for activists from around the world.

It was a diverse crowd. There were veteran activists, like Zwelivelile “Mandla” Mandela, grandson of Nelson Mandela, and Ineke Palm, a 74-year-old Dutch woman who showed me photos of herself at a pro-Palestinian protest in the 80s. The Greek delegation numbered around 200 younger activists “used to action”, as they put it to me. Others were first-timers. In a meeting of the Dutch delegation, someone asked what a keffiyeh was. Mark, a 45-year-old banker from Ireland, who asked that Novara Media only use his first name, has been active in the Palestine movement for a couple of years. When he heard about the march, he signed up right away. He had never flown before. “We have to shed light on what’s happening in Gaza,” Mark told me. “Israel is treating Palestinians like animals. They are being starved, and no aid is getting through. This is a man-made crisis, one that could be reversed so easily. Just let the aid in. I have to be here because my government is complicit.”

The marchers did not, however, include any Egyptians. From the start, the organisers were clear that they had no intention of involving Egyptian citizens in the march, as the risks for them were simply too high. While in theory, Egyptian law permits protest – organisers must simply notify authorities three days in advance. In practice, any public mobilisation, particularly in support of Palestine, is met with surveillance, obstruction or force.

Only once since the Gaza genocide began has President al-Sisi permitted a public protest for Palestine, in October 2023, to emphasise that Egypt would not tolerate Israeli plans to expel Palestinians into the Sinai. The protest was carefully stage-managed by the state, according to Al Jazeera.

Attendees were seen waving both Palestinian flags and pro-government banners. They’d been instructed to show support for President el-Sisi as well. Those who attempted to demonstrate elsewhere – outside the state-designated zone – were chased off or arrested by police. According to a Middle East Eye report published in January, at least 129 Egyptians remain in pre-trial detention for taking part in peaceful pro-Palestinian demonstrations.

Everyone knew that reaching the Sinai would be tough. Nobody expected how tough. On 11 June, the day most marchers arrived in Cairo, Israeli defence minister Israel Katz called on Egypt to block the Soumoud convoy – a land convoy of about 1,500 people travelling to join the Global March from Tunisia, through Libya, towards the Rafah border crossing and whom Katz called “jihadist protestors”.

The next day, the Egyptian government issued a public statement welcoming “foreign travellers”, also those supporting pro-Palestine movements, but also urging them to request permission if they want to enter the Sinai. The organisers told me they’ve done exactly that, multiple times, and have yet to receive an official response. They had been waiting two months.

In the days leading up to the march to Gaza, Egyptian state media and pro-government commentators began portraying the Sumud convoy as a “political scheme”. Presenter Ahmed Moussa said the convoy was a “trap” to put Cairo in an “awkward situation”. His sentiment was echoed by other pro-government voices on social media. Many Egyptians have countered these posts on social media, with comments voicing their support for the movement.

Passport privilege.

Arits made it through Egyptian border control at the airport without incident, others by the skin of their teeth. A Belgian woman of Moroccan descent, who also asked to remain anonymous, was pulled aside. Border agents searched her backpack and found an inflatable sleeping mat. “I’m a diver,” she lied. “It’s for swimming.” She mimicked a breaststroke. The agent stared for a moment, zipped the bag shut and waved her through.

Others were not so lucky: behind customs, a group of around 40 men, all of North African descent, most wearing a keffiyeh, were waiting. They were denied entry, along with around 500 other marchers.

Dutch psychologist Meryem Belhaj was stopped at customs during a layover in Istanbul. Border officials demanded proof of her return ticket. “They were on the phone with someone in Egypt,” she said, speaking from Cairo. “They sent them a photo of my flight back via WhatsApp.” According to Egyptian news outlet Mada Masr, an Egyptian government source claimed that Egyptian authorities had attempted to coordinate with departure countries to block participants from entering the country. The source said that none of the participants would be allowed to cross into Rafah for reasons of sovereignty and security.

Having cleared border control in Istanbul, Belhaj was interrogated in Cairo. “I’d booked all these tourist trips, to the pyramids and that kind of thing, to avoid suspicion,” she said. “That probably saved me … but my Dutch passport also saved me. We carry passport privilege. We can gather here, we can march, and the worst that’ll happen is deportation. Others don’t have that safety. Locals and people from neighbouring countries face far worse.”

Many participants chose not to use their hotel bookings after rumours spread that Egyptian authorities had pulled people from their rooms. One internal group chat described the incidents as “raids.” While in Cairo, I spoke to several marchers who said they had witnessed people being taken from their hotels. I also saw multiple videos of individuals being escorted to the airport. Two Dutch women called me from Paris after being detained by Egyptian police and put on a flight out of the country.

On 13 June, two days before the march start date, and as news of Israel attacking Iran spread, the organisers issued an update to participants: it was clear the Egyptian government was not willing to cooperate as expected, but they still had not received a clear “no”. So they decided to move forward with the march, though with a slightly different plan.

Plan A had been to leave for El Arish early that morning. But as it became clear the authorities were unwilling to cooperate, the organisers shifted to Plan B. Instead of travelling in buses to the desert, they would make their way in small groups by taxi to Ismailia, a coastal town about 75 miles from Cairo. There, they planned to regroup in a local hostel. It wouldn’t be a protest; the goal was simply to gather somewhere, to at least be together in one place. What would happen after that was still uncertain.

Around 2pm that day, Belhaj and Dutch activist Wouter Stroet stepped into a taxi heading east. They cleared the first police checkpoint without issue. At the second, they were stopped. Their passports were confiscated, and they were detained for hours on the street beside the checkpoint by police officers and men in military uniforms, along with around 1,000 others.

Stroet describes the atmosphere as surprisingly calm. “It was actually quite gezellig,” he says, using the Dutch word for cosy togetherness. “It was comforting seeing so many people showing up for the cause.”

Among those detained was Zwelivelile Mandela; when stopped at the first checkpoint, he and others started chanting Free Palestine. “I think the Egyptian government is showing its true colours.”

Belgian anthropologist Franssen made it only as far as the first checkpoint, where her passport was confiscated along with those of 200 other marchers. They were held for six hours outside, under the sun, in a parking lot next to the checkpoint. Just as I tried to ask Franssen why she was there, around 7pm, shouting broke out around her. “Film! Film!” someone yelled. All detainees were then forced onto buses, and those who resisted were beaten.

At the second checkpoint, a similar scene played out. “Police used force,” said Stroet. “I filmed. When they tried to take my phone and I refused, they beat me too. Within seconds, they’d deleted everything.” Filming authorities in Egypt is illegal.

At around 8pm, the 200 march participants who had been held at the first checkpoint were shoved into buses, still without their passports. The vehicles didn’t move. Men under 30 and all those with Turkish passports were pulled off. It remains unclear what happened to them.

An hour or so into their journey, the remaining activists had their passports returned. As the bus rolled on, someone read a message from a friend in Gaza: “Thank you for fighting for us.”

At around 10pm, the group was dropped off in random locations across Cairo.

The aftermath.

While most of the march participants I spoke to managed to find one another soon after being dropped in Cairo, not everyone was accounted for. The next day, a missing person alert was circulated on Facebook and Instagram. It was about protest coordinator Saif Abukeshek, who it later emerged had been detained by the police. He showed me a screenshot of a WhatsApp conversation between him and another organiser, in which he shared his location: a police station in Cairo.

“It was tough,” he recalled to me. “They did not use my name, but called me 181. I had to sleep handcuffed on a blanket. They would wake me up a lot for interrogations, and there was always noise when I was trying to sleep. They would push me around and hit me against doors. Three times they stripped me naked.” After 25 hours, he was released.

While Abukeshek is detained, the mood in Signal and Telegram groups shifted. More reports came in of plainclothes police grabbing people off the streets, from cafés and hotels – questioning them, sometimes violently, and sending them to the airport. At the time of writing, march organisers said they were trying to get exact figures of how many people were detained and how many deported.

On Monday, they released a final message to participants: the action was over. Organisers called on the Egyptian government to release all detainees, and asked participants to head home as soon as possible. Feelings swung between hope and despair. Despair at not having achieved what the group came here to do. Hope that thousands of people assembled in Egypt to resist a genocide, risking their freedom to do so.

Deflated but not defeated, Abukeshek flew to Tunisia shortly after the failed march to meet his fellow organisers, along with representatives from the Soumoud Convoy and Gaza Freedom Flotilla. “We made mistakes with the march,” Abukeshek told me over the phone from Tunisia. “But now we have a structure for new plans.” He didn’t specify what these plans were at present.

After Tunisia, several march organisers went to Brussels (Abukeshek returned to Spain, as he had to work). There, an encampment was underway to coincide with the meeting of the Foreign Affairs Council (FAC), which convenes monthly to discuss the EU’s foreign policy (while the EU officially supports a two-state solution and has called for a ceasefire in Gaza, division among member states has hindered decisive action, such as suspending the EU-Israel association agreement).

Among those stationed in Brussels was Arits. “I can feel what started in Cairo,” she told me. “We will never stop.”

Tobiah Palm is a Dutch reporter and columnist.