Could a Communist Really Win Chile’s Presidency?

One round down, one to go.

by Charlie Ebert

17 November 2025

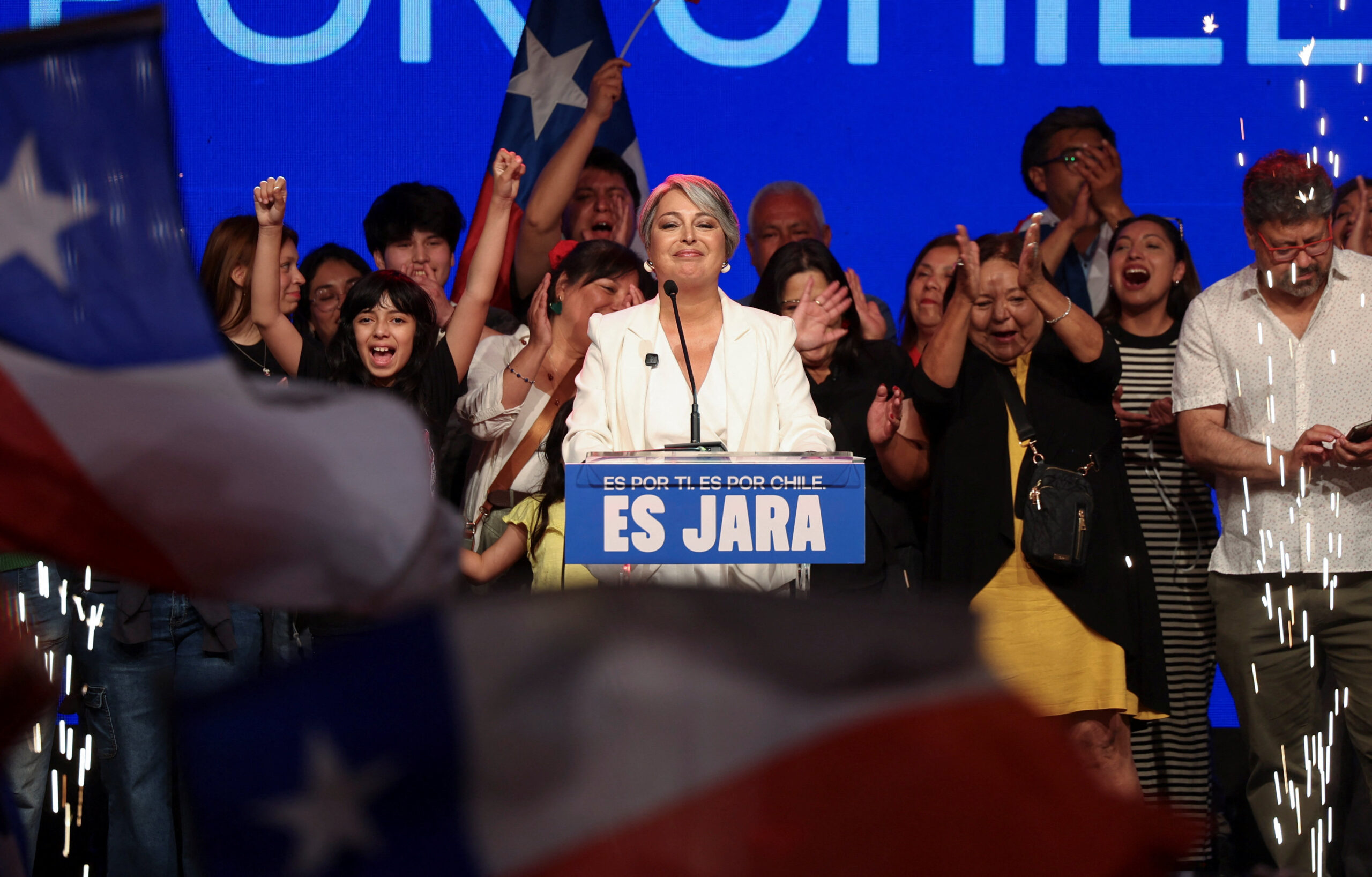

The Communist party candidate, Jeannette Jara, from the governing coalition, narrowly won the initial round in Chile’s presidential elections on Sunday. This was an unprecedented moment – not only for Chile, but for the entire region.

Despite its lefty reputation, no big-C communist party – except for Cuba’s – has ever won a national election in Latin America. Now, in the land of Pinochet and the Chicago Boys, communism is on the march. As a popular slogan in the country goes: “Chile was neoliberalism’s cradle. It will be its tomb.”

Jara faced down three rightwing reactionaries in the presidential race: right-of-centre Evelyn Matthei, daughter of junta member Fernando Matthei; far-right candidate José Antonio Kast, a pro-establishment Pinochet-apologist with a Nazi officer father; and Johannes Maximilian Kaiser Barents-von Hohenhagen, Johannes Kaiser for short – who emerged from YouTube and boasts younger, more insurgent, more alt-right and more online supporters.

Facing a divided right, Jara won on 16 November – if narrowly. Her 27% carried the day but fell well below the 50% threshold, meaning that there will be a runoff. Facing her in the second round will be Kast, who won 24% of the vote.

The biggest surprise was the performance of Franco Parisi. An economist representing an eclectic populism, he increased his vote from 12% in 2021 to nearly 20% this year. Kaiser and Matthei, for their parts, won 14% and 12% respectively.

While running on a platform far more moderate than the party’s 2021 manifesto – when their candidate called for a “medium term” transition to socialism – Jara nonetheless represents a significant break from neoliberal orthodoxy. She’s promising to substantially hike the minimum wage and raise the carer’s allowance, and to construct 260,000 homes.

Kast, in contrast, combines a radical pro-market programme of business deregulation with an authoritarian approach to law and order and a full-throated opposition to immigration.

A generation ago, Jara’s result would have been unimaginable. Augusto Pinochet, dictator from 1973-1990, had shattered the Communist party. Thousands of its sympathisers were killed, hundreds of thousands exiled. Despite leading popular opposition to the dictatorship, the Communists were then sidelined by ‘moderates’ during the democratic transition. The party became a marginal force; a large membership but gaining no more than 5%-10% of the vote in elections.

The mass protests of 2019-2020 changed all this. Dubbed the estallido social [social outburst], millions took to the streets against inequality, unaffordability, police brutality, patriarchy and more. Dozens were killed. The uprising lasted six months and in the process, the existing party system was shattered. While then-president Sebastián Piñera survived the crisis, he could only do so with the aid of the parliamentary opposition. In exchange for this act of political-class solidarity, they extracted from him the promise of a new constitution.

A referendum was held on whether Chileans wanted a new constitution. The result was overwhelming: 78% yes. When electing officials to the convention tasked with drawing up the constitution document, over two-thirds came from the left. Gabriel Boric – a leader of Chile’s 2011-2012 student protests and self-described “feminist” – was elected president.

That’s where the left’s luck ran out. The resultant constitution was defeated in 2022, with nearly 62% against. Boric swung right. Some minor gains were enacted, including increased pensions and a higher minimum wage. But overarching structures remained static. Meanwhile, the ex-protester unleashed an enormous wave of repression, with informal settlements raided and destroyed. Boric’s popularity plummeted.

In this context – defeat, confusion, moderation, repression – the left decided to hold a joint primary for the first time ever. The hope was to avoid an electoral massacre. The heavy hitters, led by ex-president Michelle Bachelet, decided to sit it out and into the vacuum walked a plain-talking ex-bureaucrat with a folksy charisma, a mechanic’s daughter turned labour minister. Jeannette Jara not only triumphed, winning over 60% of the vote – more than double that of her nearest rival – she managed to hold the coalition together.

However, Jara’s prospects in the presidential election’s second round – to be held on 14 December – are difficult to gauge. She’s behind in the polls, and the right took a combined 50% in the first round. But approximately a third of the country remains undecided. Importantly, Sebastián Piñera – who was at least somewhat critical of the Pinochet years – remains the only rightwing president in Chile since the 1950s. Kast is much more radical.

Even if victorious in the runoff, however, Jara faces an extraordinary task. She will not hold a majority in congress. She won’t even hold one on the left. Legislating will likely prove difficult – if not impossible.

Nonetheless, she must avoid the mistakes of Gabriel Boric: repression and moderation. Instead, she should look to the Allende period when groups from the Cordones Industriales to the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR) exerted extra-parliamentary pressure to collectivise workplaces and appropriate land. The result was more far-reaching than anything Allende could have achieved through parliamentary means alone.

Despite these challenges and limitations, however, this is a bright day for the left. For the first time in the history of the western hemisphere, a communist party outside Cuba has won an election.

Charlie Ebert is a writer, researcher and activist previously based in Santiago, Chile.