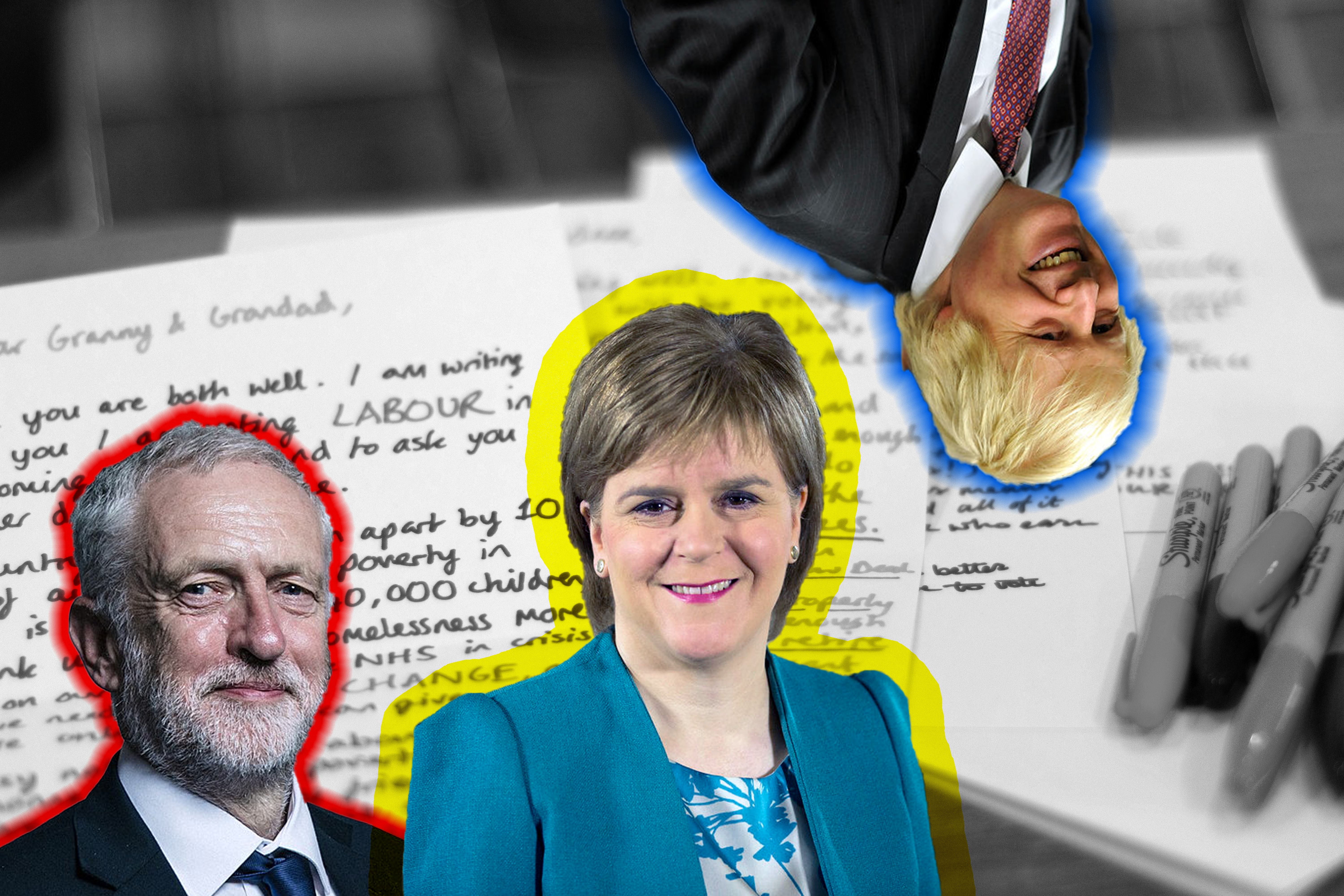

Beg Your Granny: In Scotland, Young People are Helping Labour Fight Perceptions of its Past

by Simon Roach

6 December 2019

The electoral dynamics in Scotland are very different from those in the rest of the UK, and its 59 seats are often decisive in a general election. 2019 will be no different. With the historical infallibility of Labour support in Scotland having long since melted away, this election will hinge on whether Jeremy Corbyn can cut through the veneer of SNP progressivism.

It is mid-afternoon in Glasgow city centre and the slow winter sleet has already set in. The Sunday light on Sauchiehall Street is darkening, it will be gone long before evening, and only those with somewhere to get to are outside, hurrying under the freezing rain. At the street’s centre, nestled between the city’s bars and clubs, some activists are campaigning around the general election—but today they are glad not to be out canvassing. They are writing letters instead.

Inside the warmth of the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Giuilia and Hussein have brought coloured pens and paper, and are making tea and coffee for folk as they sit writing to their grans and grandads, aunties and uncles. “I know you don’t necessarily think Jeremy is the best leader in the world,” one letter reads. “But his ideas and principles make him the best chance we have at making the world a better place.”

- No False Consolations

- Banking on Brexit: Is a Pro-remain Platform Enough to Win Canterbury?

- This Election Campaign Showed the Left’s Power. Win or Lose We Must Continue to Build a Socialist Future

More than just a cute gesture, Hussein says he came up with the idea of asking young people to write to their conservative elders after an intervention by Owen Jones in 2017, one week before the election, called Call Your Grand Folks. The idea behind both initiatives is simple: if we can only transgress the shy awkwardness of speaking with family about politics, or even the fear, then we open up huge spaces for transformative conversations which may even, perhaps, change minds.

“We wanted to facilitate something where young people could express the importance of both the social crisis and the environmental crisis with older people who might not be engaged,” he said.

“But it also suits people who don’t want to do something as extroverted as going out canvassing – it provides a space for people who want to be part of the effort to elect a different government but perhaps want to do it in a different way.”

The general election result in Scotland, like everywhere else, is seen to hang on how many young people vote in comparison to the old. But are those voting intentions as fixed and immutable as we think?

“I really hope other groups do it, it could be really effective,” Hussein said.

“There are 500,000 Labour activists in the UK. If each one of them were to write a letter to someone they know that’s a Tory, and even if that has some level of traction, then a swing vote switching from Tory to Labour could decide who’s in Number 10.”

“It seemed very much like Labour were siding with the Tories.”

But divergent politics between generations are where Scottish comparisons with the rest of the UK end. For example, unlike its analog in England, Scottish nationalism is still thought of as a relatively progressive position and is, peculiarly, internationalist; 62% of Scots voted to remain in 2016, and the SNP continue to be vocal remainers since. More broadly, much is made of the Scots’ historical leaning toward socialist, working class politics which even today sets a baseline consensus further to the left than its neighbours.

But while this should make Scotland fertile ground for Corbyn and his policies, it is more recent events – namely the optimism of the 2014 independence referendum, and subsequent dominance of the SNP – which have stood in the way.

“I think it was partly the scene in 2014 with Better Together [the campaign against Scottish independence],” Hussein said. “It seemed very much like Labour were siding with the Tories.”

In the 2017 general election, the surprise surge was in fact for the Tories, who gained 12 seats to make a total of 13 – predominantly in the oil-rich or fishing communities of the North East – and took their largest share of the popular vote since 1979. Next to the relative gains Labour made everywhere else in the UK, and given its erstwhile dominance north of the border, gaining six new Scottish seats to reach a total of seven was seen as disappointing by the party. Especially so given that the SNP had lost 21 seats, following on from the 2015 election where they won 56 of Scotland’s 59.

The letter writers remember what happened in 2017, but hope the ground is shifting. Giulia is 22 and from the south of Glasgow, not far from the national football stadium at Hampden Park. She says the lukewarm Scottish response to Corbyn, even from parts of the left, has been twofold: driven in part by Scottish Labour’s lingering association with Blair-Brown-era acolytes, and by the imaginative space taken up by the SNP as the progressive vote.

“The way that the SNP has got such a foothold in Scotland is because for years they outflanked us with policies from the left,” Giulia said. “It’s not like they delivered on most of it, but there’s at least that perception.”

Giuilia, like the majority of Glaswegians, voted yes in the 2014 independence referendum. “I think a lot of my friends are still SNP members, because that campaign had so much hope and energy behind it,” she said. “In that way it was convincing, but I think looking at it now, and knowing what I know now, I think I’d have said no.”

For many young people, Scottish independence was never about nativism or, confusingly, even tradition. Rather, in 2014 independence was the only available route to breaking away from the neoliberal consensus in Westminster – something Giulia says Labour now offers the best vehicle for. She has been out canvassing around Glasgow and she says her experiences have been encouraging.

Everything could change.

Partly the reason Scotland is so pivotal to this year’s election is that so many of its constituencies hang on a knife-edge. Of the total 59 seats, 46 were won in 2017 with a less than 10% majority, which most analysts would see as marginal. Pollsters suggest that as many 18 seats are likely to change in December.

But so far, Labour polling in Scotland is not looking good. Trust it or not, recent YouGov data suggests that the SNP is set to gain eight seats this year, taking five from Labour, two from the Tories and one from the Liberal Democrats. Some had predicted popular Scottish Tory leader Ruth Davidson stepping down in August would lead to a collapse of the Conservative vote, but so far it seems to be staying firm. Some polls suggest the Tories may only lose one seat.

This brings a question for many on the left of whether to campaign explicitly for Labour, or for whichever party can beat the Tories. The proposal to campaign in Labour/SNP marginals has been a point of contention, says Hussein, who has been involved in both non-partisan registration drives and canvassing for Labour. The disagreements are part ideological, part strategic: in principle, should you only settle for a Labour majority government, despite the odds? Or, in practise, do you believe as many do that, that despite Corbyn’s assertions Labour would happily form a coalition with the SNP if it meant keeping the Tories out?

As recently as last week Corbyn stated adamantly that he would not partner with the SNP, but this should come as no surprise. No leader would campaign openly for a coalition, and yet only the most hubristic would turn down a partnership if it paved a clear path to government.

In 2017 Labour came second in 25 of the SNP’s 35 seats, some of which are marginals in Glasgow. Hussein and Giulia are hoping this year, like two years ago, the polls can be bucked.

“If you look at the campaign in Glasgow North, they’ve been getting out 50-odd people everytime they do a session,” Hussein said. “Look on Twitter — it’s just full of activist pictures that you wouldn’t have seen in 2017.”

Giulia’s grandma is in her mid-80s now, an Italian immigrant who came to Glasgow via France in the early 60s and never left. Giulia says part of her own politics is influenced by not knowing what would happen to people like her grandma if Brexit ended with Boris Johnson’s deal. Her grandma’s been a lifelong Conservative voter, which Giulia has recently started speaking to her about.

“I remember she came around to me recently and goes, ‘I might actually vote Labour this election’ and I almost died,” Giulia said. “I think I’m gently winning her over.”

Simon Roach is a journalist based in Glasgow.