Filth: Racist Scaremongering Around Covid-19 Is Nothing New. We Have Always Blamed Racial Others for Disease

by Eleanor Penny

24 April 2020

Donald Trump has taken to calling Covid-19 the ‘Chinese virus’ or even ‘kung-flu’. He has approvingly shared memes of himself duking it out against the virus in martial arts matches. Boris Johnson’s government, meanwhile, has attempted to squirm out of a self-strung noose by blaming the virus’s spread on a dissembling Chinese government.

Across Europe and northern America, coronavirus has been accompanied by a surge in hate crimes aimed at whoever, in the assailant’s rough estimation, passes for Chinese. Businesses have been vandalised, people have been attacked in the street. Earlier this month, a man was arrested for stabbing an Asian American family – including two children aged 2 and 6 – “because he believed they were spreading the coronavirus”.

As the pathogen spread, so did horrified rumours about the supposedly putrid conditions of Chinese ‘wet markets’ from which the disease is thought to have originated, about the fantastical diets of far-off peoples dining on fruit bat soup. In reality, wet markets are no more than fresh food markets which often sell live produce – comparable to those found across the UK and across the world.

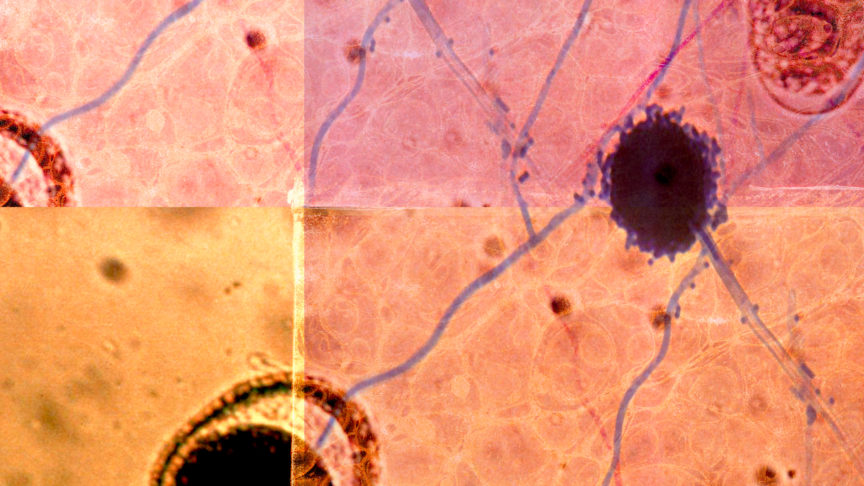

Zoonoses leaping from animal to human hosts have much more to do with patterns of expanding agribusiness and ecological breakdown that disrupt habitats and bring unexpected encounters with other species, than with wet markets. To a certain extent, zoonoses have always dogged human civilisation as products of urbanisation and evolving agricultural practices. But talk of an exotic sickness, sprung from the filthy habits of foreigners, just harmonises too nicely with a background hum of xenophobia for us to hear that something might be amiss.

Cadences of disgust around food are familiar in our culture’s chorus of racism; the complaint that one’s neighbours might ‘smell of curry’, the dismay that other cultures might consume dogs, insects or bats with the aplomb we reserve for slaughtering pigs, shellfish and rabbits. In Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the fainting whites are infamously served up dishes of chilled monkey brains and eyeball soup by their murderous Indian hosts. It’s all terribly dangerous, terribly savage, terribly foreign.

Stigma sticks less easily to other populations with a high coronavirus infection rate – such as Italians, or the British royal family. They don’t suffer from public preoccupations that they might be privately burdened by a cultural pathology of disease. Inexplicably, we don’t assume that the Windsors got coronavirus because they’re a filthy band of degenerates who barely wash at the best of times.

A glance over the history of colonialism and race-making reveals a longstanding tradition of scaremongering about racial others as founts and bearers of disease. Titillating travelogues of orientalist writers in the 18th and 19th centuries unfurl tales of a dark, bloated and pestilent East brewing with currents of moral and physical sickness ready to pull the unsuspecting colonist under.

“In Malaya, the British aged quickly, the climate drove former public school boys to suicide, and colonial emissaries all turned to drink,” writes historian Warwick Anderson, surmising playwright Somerset Maugham, and a tradition more broadly.

Gustave Flaubert described with delicious theatricality the “pretty cases of syphilis” he saw groaning on the fringes of his gallant path through the Orient; the rickets, the open sores, the heads “ringed with whitish leprosy”. Even the famed local seductresses were tainted with the “nauseating odor” of bedbugs, mingling enchantingly with the scent of skin.

Edward Lane’s ‘An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians’, first published in 1836, tells that “few Egyptians live beyond a few years, because of fatal illness”. Africa was painted as a plague-ridden heart of darkness. A pneumonic disease in Manchuria in 1910 was taken up by French newspapers as yet more proof that China remained a backwards sink of contagion, in need of further civilising influence.

Unruly Indians in the British Raj were accused of spreading the blue terror of cholera, their “very loose habits” a natural conduit of the disease. Contemporary historians relate that the disease was more likely transmitted by the movement of colonial soldiers. Venereal diseases in particular were taken as proof of the “primitive” sexuality of the non-European, more fodder for the skull-fondling predilections of eugenicists and race scientists keen to organise humanity into a hierarchy of races.

Social Darwinism reigned supreme, as pseudoscientists keen to forge a biological explanation of political power structures dreamed up an image of non-caucasian bodies as inherently weakened, disease-prone and deviant. Thus, older stereotypes about fastidious Indian hygiene were ousted in favour of the ‘doomed creatures’ Rudyard Kipling charted in the fevered streets of Calcutta, whomst it was his cumbersome duty to save, disease yet more proof of native savagery which had to be tenderly stamped out by the grasping aspirations of colonial plunderers. The clinical overtures of the civilising mission disguised economic ambition as public health policy.

That new diseases of European contact were known to wipe out indigenous populations in Australasia and the Americas was held as further proof of their perilously inferior constitutions. Indeed, competing ranking systems of racial hygienists sometimes depicted racial otherness itself as a medical condition; ‘Mongoloid’ was both shorthand for someone with Down’s syndrome and a racial category in the Göttingen school of scientific racism. The Nazi regime painted Jewish people as rats; both carriers of disease, and a civilisational disease themselves.

Pandemic panic can sharpen older cultural anxieties to a dangerous point. Gnashing xenophobics have gleefully stoked fears that migrants might carry diseases, rehearsing a script played out every time a terrifying disease hits the headlines. Katie Hopkins has described non-European migrants as “cockroaches” and “a plague of feral humans”. Ebola was touted as a reason to crack down on migrants from Africa – and, like the Aids crisis, a reason to stoke old colonial tropes of Africa as a pathologically doomed continent. Undocumented migrants to America have been accused of traipsing with them a bristling pack of diseases including tuberculosis, hepatitis and dengue fever. White supremacists like Patrick J. Buchanan and Frosty Wooldridge, blamed swine flu on “cultures that lack personal hygiene, personal health habits and standards of disease prevention”.

A new generation of frothing reactionaries has recycled these lines for Covid-19, with Tucker Carlsonites spreading conspiracy theories pinning the disease on Chinese culinary customs. It’s nothing if not violently unoriginal. An 1854 New York Daily Tribune article claimed that Chinese people were “uncivilized, unclean, filthy beyond all conception”.

They are baseless paranoias are dredged up from an addled racist imaginary; indeed, studies have found that migrant populations tend to prioritise health and hygiene more. But such theories were never exactly straightforward in their epidemiological intentions. Colonialists cloaked their economic and territorial ambitions in the clinical language of social sanitation; contemporary dial-a-crank racists veil their hateful politics as the understandable anxieties of those trying to beat back a deadly biological menace. And all the while, disease sufferers are transformed into disease carriers. Stripped of humanity, they are no longer people needing care and empathy, but a dehumanised threat needing to be neutralised by any means necessary. A very powerful mandate indeed.

Geopolitical allegiances are cracking and shifting, China ascends as a global superpower to rival the American hegemon. Meanwhile, European and North American governments are floundering as their flimsy efforts to contain the virus reap bitter consequences. They have every reason to opportunistically stoke sinophobia, to distract, to dodge blame.

But the old deliriums of scientific racism and orientalist scaremongering are useless to protect us against a virus that recognises no borders or nations, a pathogen that brooks little difference between one warm-bodied host and another.

Eleanor Penny is a writer and a regular contributor to Novara Media.

This article is the second instalment in a new series on the political economy of things we consider to be waste, rubbish, junk – or filth.

Part one is here: Trans Bathroom Panics May Be New, but Public Toilets Have Always Been a Political Battleground