How We Won: The Activists and Lawyers Who Stopped Asylum Seekers Being Evicted in Glasgow

by Lauren Gilmour

14 September 2020

Over the course of 2018 and 2019, housing provider Serco attempted to evict hundreds of asylum seekers in Glasgow, threatening to make scores of vulnerable people street homeless by changing the locks on their accommodation.

Campaigners accused the company, which was contracted by the home office to house asylum seekers in the city at the time, of using destitution and homelessness to enforce the government’s draconian immigration agenda.

It offered no time for residents to arrange alternative accommodation or support, or even to pick up their belongings. At a proposed rate of 30 evictions per week, charities warned the move would completely overwhelm services in the city.

“Asylum seekers were spread out across the city, so they couldn’t organise or support each other,” explained Leo Plumb, an organiser with tenant’s union Living Rent, which helped organise a grassroots campaign against the lock-change evictions.

Resistance.

Glasgow already has the most acute homelessness problem in Scotland, with over 5,500 homelessness applications made in 2018-2019 – 2,500 more than in nearby Edinburgh. Worse still, those threatened with eviction by Serco were legally prevented from making homelessness applications or accessing local authority shelters due to their immigration status.

But the city also has a rich history of organising around housing issues, tracing back to a 1915 rent strike led by Govan resident Mary Barbour against poor conditions in the city’s tenements. An estimated 20,000 tenants joined the strike, which inspired similar campaigns across the UK and led to national housing reform.

More than a century later, the struggle for safe, secure and quality housing rages on. Within a week of Serco first revealing its plans in summer 2018 to evict asylum seekers whose applications had been denied, activists, lawyers and third sector organisations including Shelter Scotland had convened to discuss how to resist.

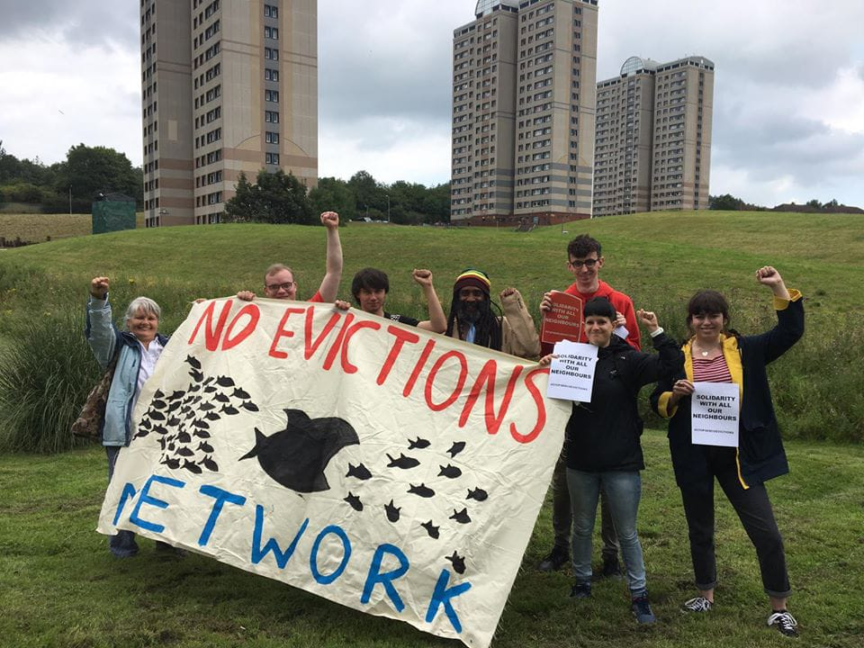

It was agreed that there would be two separate groups. Shelter, Legal Services Agency and law firms Latta & Co and the Govan Law Centre immediately established legal surgeries for people at risk of a lock-change eviction, while Living Rent and the No Evictions Network led a new campaign of awareness-raising and direct action.

Plumb told Novara Media how he recruited volunteers and activists to help run street stalls, publicise petitions and obstruct bailiffs. “The campaign asked a lot of people,“ he said, ”[we would ask them] to sit outside properties or inside flats with asylum seekers to stop bailiffs coming in. There was a core group of activists who were very disciplined”.

Plumb reeled off a list of tactics: demonstrations where people burned notice to quit letters; anti-eviction teams across the ten areas of the city with the highest density of asylum seeker accommodation; vigils where evictions were due to take place, sometimes two or three on the same day.

“We built a coalition with Glasgow’s Unity Centre and other organisations that support refugees and asylum seekers, which was crucial because they had much more experience,” he said. “The campaign wouldn’t work without the input and involvement of asylum seekers and refugees.”

Ana, who became involved with the No Evictions Network, in August 2018, told Novara Media that in addition to holding demonstrations the groups supported two people directly affected by the evictions when they went on hunger strike.

Activists also reached out to the media and lobbied Glasgow City Council, the Scottish Government and the Home Office.

Former Labour MP for Glasgow North East, Paul Sweeney, quickly joined the campaign. “I had full support for the people who were prepared to take direct measures against Serco including occupations and picket lines,“ he told Novara Media, adding that many of the evictions due to take place were within his constituency.

Legal challenge.

While direct action bought the campaign time, Shelter Scotland and Legal Services Agency took Serco to Glasgow sheriff court to acquire interdicts to stop individual evictions.

Meanwhile, Govan Law Centre lodged a case with Scotland’s highest court, the court of session on behalf of a client identified as Ali, and at the same time Latta & Co sought a more comprehensive judicial review to rule on the legality of the lock change policy more broadly.

Under mounting legal and public pressure, and facing a logistical challenge from activists, Serco temporarily shelved plans for lock-change evictions.

“The massive solidarity and a legal case raised by organisations supporting asylum seekers in Glasgow forced Serco not only to postpone the lock changes but also to lose the contract for asylum seeker accommodation in Glasgow,“ Ana explained.

But Plumb says neither Living Rent nor the No Evictions Network stepped down their campaigns. “At the time, it didn’t feel like a success or a victory – these people are still at risk of eviction,” he cautioned.

Evictions resume.

In June 2019, the Ali case was refused, and Serco announced it would resume lock-change evictions, despite the policy not yet having been deemed lawful by the court of session. The coalition fighting the evictions maintained that Serco should not evict asylum seekers until a final legal judgement had been heard.

Quickly, activists mobilised. This time, Living Rent focused on outreach, organising with the No Evictions Network to bring together activists once again. The union set up teams in the four broad areas of the city and sometimes had two to three meetings running a night. “Every week there was a massive action against Serco. One week we put a chain around their entire office,“ Plumb said.

In one particularly memorable direct action, Living Rent led activists in occupying the Caledonian Sleeper service, a train between Glasgow and London operated by Serco.

Activists stormed the train and put flyers in the windows and berths, as well as loudly protesting on the platform and confronting security staff. “It made Serco shit themselves,” said Plumb, “they had no idea it was coming”. Living Rent pledged to continue disrupting Serco’s business interests until it stopped evicting asylum seekers.

Leo Plumb/ Living RentIn the summer of 2019, as the initial interdicts expired, the legal group filed more and more, sometimes overwhelming the court. Serco instructed their lawyers to object to the emergency applications, but in the vast majority of cases, the court sided with the asylum seekers. By August 2019, 159 interim interdicts had been granted.

Ultimately, Serco’s lock-change evictions were deemed lawful in November 2019. But by then Serco’s contract to provide housing for asylum seekers in the city had come to an end, and a different provider, The Mears Group, had taken over in September 2019. The new landlord has pledged to provide better support to asylum seekers and replace lock-change evictions with a proper court process.

Through direct action and legal proceedings, activists and lawyers in Glasgow were able to prevent the lock-change evictions from happening. However Plumb cautions that this is a small victory. Living Rent and the No Evictions Network still regularly have to challenge asylum seeker evictions in the city. During the pandemic, the Mears Group moved dozens of people from their usual housing to hotels, which they were allegedly locked inside to prevent them from speaking out about poor conditions.

While Serco no longer operates accommodation in Glasgow, towns and cities in the Midlands, North West and East of England can expect to see similar scenarios in coming years – in January, at the same time it lost the Glasgow contract, Serco won 10 years of contracts for housing provision for asylum seekers in these regions.

Campaigners and caseworkers say asylum seekers will continue to experience low-quality and precarious housing until they are given the same rights as other tenants in the UK. Sheila Arthur, director of Scotland-based charity the Asylum Seeker Housing Project (ASH), told Novara Media last year, “until the law is changed, we are going to keep seeing brutal and inhumane actions such as these – no matter who holds the contract“.

In Glasgow, however, Ana said the campaign has had a lasting impact. “The biggest achievement of the campaign has been building a collective space where people have been able to share their experiences, build power together and support each other and the broader community,“ she said. “A collective space ready to challenge borders and the injustices caused by immigration politics.”

Lauren Gilmour is a freelance journalist based in Scotland.

This article is the second instalment in How We Won, a new series which celebrates the victories of grassroots campaigns across the country.

Part one is here: The Customers Who Saved Their Local Market