Faced with crystal-clear warnings from the IPCC and rising public consciousness around the climate crisis, last year the British government committed itself to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. The scientific case for why a mid-century target is likely to be too little too late has prompted a generation of more ambitious targets, such as decarbonising (rather than avoiding decarbonisation with a misleading ‘net zero’ goal) by 2030.

By any measure, decarbonising the country will be a seismic effort. But while popular support for ditching fossil fuels has arguably never been higher, nuclear energy remains a thorny and far less discussed issue despite offering masses of power without releasing carbon into the atmosphere, and requiring a fraction of the space requirements demanded by solar energy in particular. While there’s no denying accidents at nuclear power plants can be devastating, high-profile disasters have had clear and specific reasons, and on average nuclear energy ranks as one of the safest energy sources in the world.

There was a time when the left’s stance on nuclear energy appeared a foregone conclusion. In recent years, however, many environmental groups have very quietly softened their opposition. Nuclear energy quite simply isn’t a threat to humanity in any way that is even comparable to fossil fuels, and whilst the uranium required for nuclear power does come ‘from the ground’, it is fairly abundant and far more evenly distributed across the globe than oil or gas. Although it’s evident nuclear energy isn’t anywhere near the top of most green agendas anymore – if it features at all – the pressure of the carbon reduction targets we need to achieve means having a conversation about the options available to us to decarbonise within the shortest time-frame possible, whilst simultaneously strategising about the future of energy production for decades to come. In that context, is it time for the left to actively support nuclear energy?

Greening the grid.

Across total consumption demand, the UK’s energy mix is overwhelmingly dependent on oil and gas. As we would expect, much of this can be attributed to road and air transport, as well as use in household heating systems and industry. Yet the UK’s reliance on fossil fuels extends to its use in the production of electricity, meaning a total switch to electric vehicles or boilers can only ever be part of a decarbonisation plan. At the time of writing, gas turbines accounted for 41% of the power generating the grid, whilst 9% of the ‘renewables’ on the system were actually carbon-emitting biomass, which some might argue is only really renewable in a philosophical sense.

Among the most significant tasks ahead of us, then, is to bring about a scenario where the country’s electricity is generated at all times without burning fuels which emit CO2. Although the most desirable and obvious solution might be to power the grid with 100% renewable, non-carbon emitting fuel sources – in the UK primarily wind and solar – it’s a solution which ignores some significant obstacles. Even if we bracket issues like the impact to wildlife caused by wind turbines and the not insignificant matter of finding space for solar panels with all the public buy-in such a massive expansion in capacity would require, it remains the case that the technicalities of achieving a 100% renewable grid in the UK mean it is almost certainly not the most direct route to decarbonisation.

It’s important to understand a little about the principles underpinning an energy grid. Its most obvious requirement is energy capacity, ensuring there is always enough power supply to meet demand. Evidently, in principle both the sun and the wind provide energy in abundance, provided we could add enough wind turbines and solar panels to the grid, even if it would take up an enormous amount of space. Just as important, the grid requires flexibility to ensure supply follows demand in real time on a minute by minute basis, ensuring the system doesn’t suffer either a power surge or blackout. Gas is generally the go-to fuel source for flexibility because it can be turned on and off very quickly and provides predictable capacity each time. Of course in principle solar panels can also be disconnected quite easily if they need to be, or wind turbines can be turned off.

But the third component the grid requires is stability, which is not a quality of solar or wind power. Specifically, the grid relies on inertia for stability, ie energy sources which have the quality of being resistant to changes in input by virtue of the fact they power massive turbines which are hard to slow down, and which can therefore add energy to the grid in a way that is predictable and steady. Coal provides lots of inertia because when it is burned it creates a steady source of energy for the turbines it powers. Unfortunately, solar and wind don’t provide the grid with any inertia. But nuclear energy does.

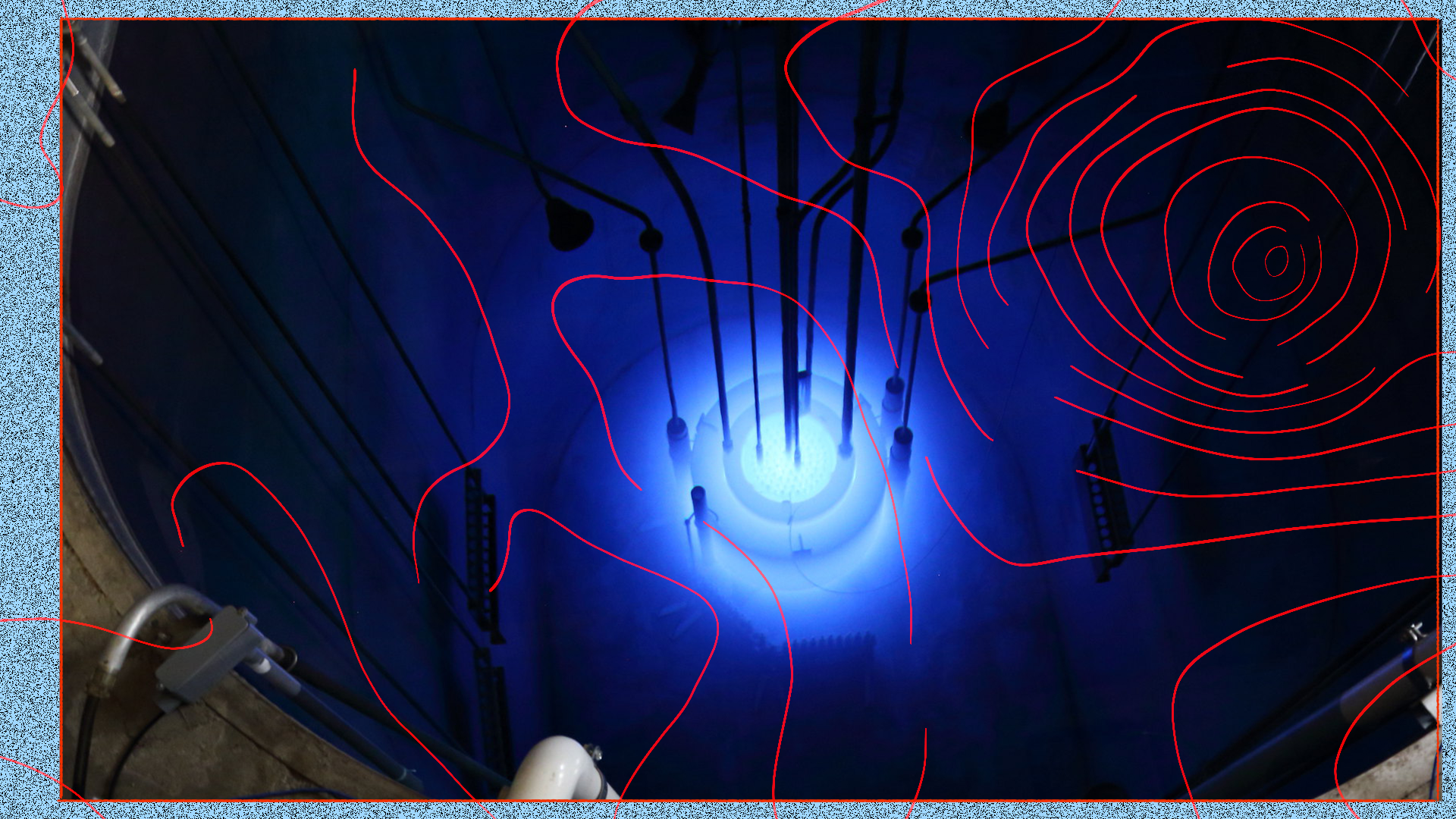

Nuclear energy currently provides the national grid with around 15-20% of its power, providing a steady supply into the grid’s baseload – the level of supply a grid requires at all times irrespective of variations in demand. Compared to the column inches attracted by renewables and fossil fuels, nuclear energy represents an overlooked portion of the UK’s energy mix. But in terms of capacity it is unrivalled because it requires so little space to produce so much energy; moreover, it is among the most reliable sources of inertia available to us and it produces energy without emitting CO2.

Constructive ambiguity.

Perhaps because recent warnings have sharpened our priorities around carbon emissions, many environmental groups are now very quiet about nuclear energy. Ecosocialist groups approached for inclusion in this article declined to speak on the record, and there exists a concern amongst some leftwing greens that adopting an explicitly pro-nuclear position as part of a wider move towards a renewable-led economy would alienate the rest of the climate movement, specifically older generations of climate activists, for whom opposition to nuclear energy is a totem.

Yet following an independent review commissioned by the group, Friends of the Earth shifted their position on nuclear in 2014, and whilst their policy argues for no new nuclear power stations to be built, it also says: “We do not oppose research into new potentially safer forms of nuclear power; but our current assessment is that we are unlikely to need them in the future.” A spokesperson confirmed nuclear energy is not something the group actively campaigns on. Meanwhile, although Greenpeace maintains nuclear energy is “dangerous”, it leads with the argument that it is uneconomical and therefore “doesn’t make sense”.

It is important to say something about safety because radiation leaks are dangerous, if rare. It is plainly true that nuclear disasters in the past have been devastating, but generally they have been attributed to either specific design flaws (as in the case of Chernobyl) or corporate corruption which ignored safety recommendations regarding nuclear reactors in seismic zones (as with Fukushima). On the whole nuclear energy is very safe, and whilst disposing of spent nuclear fuel in the very long term is an unsolved (though arguably not insurmountable) problem, we’re dealing with relatively small quantities and many modern reactors recycle waste for further energy production.

But the quiet surrounding nuclear energy suggests anti-nuclear activism is today something of a relic within the domestic environmental movement. Instead, much of the left opts for the line “we should be investing in renewables instead”. It’s a perfectly reasonable impulse, not least because nuclear energy does speak to a firmly 20th century, centralised mode of organising energy in the face of the democratic and decentralised possibilities of solar and wind. There is also the significant factor that in contrast to the speed with with renewable energy sources can be built, nuclear power plants take nine years on average to be constructed (a process which itself can be carbon intensive, of course, even though the energy produced by the plant ultimately makes a power plant’s carbon intensity comparable to wind power). But stating which energy sources we would prefer and why doesn’t deal with unresolved questions of infrastructure which need to be answered if we genuinely hope for a transition away from all fossil and carbon-burning fuels.

The decarbonisation we want.

To be clear, it’s not that we have no choice about how to manage capacity, flexibility and stability across a national grid. One option not involving nuclear would be to have a simply enormous amount of decentralised renewable energy sources coupled with massive energy storage systems which could store the excess when demand dips below capacity, in turn providing stability when sun or wind conditions are unfit. Current ideas include the creation of giant batteries or developments in hydrogen storage, both of which the government says it wishes to explore. The problem is that the technology just isn’t there yet. At present, one widespread hope is that before long electric cars will be able to provide the grid with thousands of smaller, more distributed batteries (albeit lithium batteries don’t come free from their own environmental problems), but that plan is heavily dependent on the mass adoption of electric cars and the creation of charging infrastructure to suit.

There could be a more ambitious solution yet. There are a growing number of people in the energy community who argue the conception of energy supply being divided into baseload and variable supply is outdated and does not take account of the way domestic renewables are beginning to change the grid. If solar panels are connected to a home whose demand is less than the energy being supplied by them, for example, it puts negative demand onto the grid. At present this isn’t something the national grid is set up for, because it runs counter to the way energy supply was always understood in the past, but with the right storage technology it is possible to imagine a neighbourhood battery or energy trading system. But probably not by 2030.

It is continually worth making the case for what sort of grid we would like in the future, even just to spur technological development on to meet the vision. But it’s also important to ask what sort of national grid – and therefore what form of decarbonisation – we could actually achieve within a decade. That means actively discussing the role of nuclear energy within a decarbonised energy system, because although it’s imperfect, we have to begin with the infrastructure we’ve inherited.

Clearly, if a 100% renewable grid was technically feasible tomorrow or in five years it would be preferable, likewise if the UK had access to geothermal power or masses of hydroelectricity. It might be more desirable still if we had properly international grids, where we could collectively make use of different geographies to best harness natural energy. The left may have wins to come on all these things, just as it has already succeeded somewhat in forcing the discourse on climate targets. But for the same reason, we should stop being shy about nuclear energy, because if we’re serious about rapid decarbonisation, it’s a part of the equation.

Thank you to Ellen Webborn at the UCL Energy Institute for providing further background on energy grids.

- The Climate Focus is part of Novara Media’s Decade Project, an inquiry into the defining issues of the 2020s. The Decade Project is generously supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (London Office).

Craig Gent is Novara Media’s north of England editor and the author of Cyberboss (2024, Verso Books).