‘It Felt Beautiful and Precious’: Reflections on the Student Movement 10 Years On

by Matt Myers

9 December 2020

This year marks the tenth anniversary of the 2010 student movement, which saw hundreds of thousands of students mobilise in a radical social movement to defend public education, after decades of relative quiescence.

The mass movement began in response to the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government’s announcement that it would be tripling university tuition fees and scrapping grants for working-class students. Many felt deeply betrayed by the Lib Dems, a party who only a few months before had pledged to abolish tuition fees.

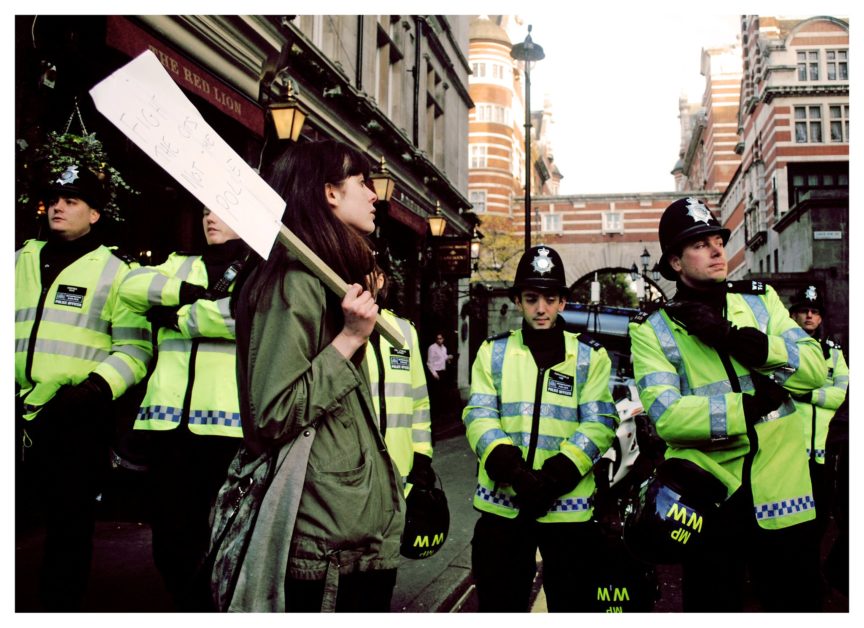

Soon most of Britain’s major universities were occupied, along with a number of schools. Walkouts erupted across the country on the major days of national action (24 November, 30 November, 9 December) after the symbolic Millbank demonstration and the occupation of the Conservative party headquarters on 10 November.

Although the revolt was ultimately defeated thanks to the government’s intransigence and the failure to secure a sufficient Liberal Democrat rebellion, its impact can still be felt today. The most important progressive social and political movement institutions of the following decade have had activists politicised by 2010 at their heart – Novara Media included. Yet more than this, the 2010 student movement was a premonition of the inter-generational cleavage that has re-ordered British electoral attitudes. Youth political protagonism is likely to continue to drive progressive alternatives to the present economic, climate, and health crisis. The current wave of occupations and rent strikes spreading across British universities should offer hope that the 2010 generation’s political project will, at last, be realised.

Novara Media spoke to two former students about how the movement impacted their politics and lives.

‘I felt alive in a way I never had in my placements as a medical student.’

Rita Issa is an NHS doctor, academic and activist based in London. She was a student at University College London (UCL) 2006-2012.

A decade on, friends I made during the UCL occupation still describe the cold months we spent fighting the rise in university tuition fees and scrapping of the [Education Maintenance Allowance, a grant for working-class students] as life-changing. For me, there have been few other moments of transformation of such magnitude in so little time. My naive and sheltered belief to not question authority, politics and the police – I was raised by religious parents who learnt in civil war that it’s best to keep your head down – was shredded and set alight in Parliament Square, Millbank and UCL’s Jeremy Bentham Room. It was an affront to my values that Nick Clegg lied, students were being hit with massive debt (and truncheons when affronted) and the media didn’t care.

I turned up to the occupation with my sleeping bag, alone and preoccupied that others might think I was a cop based on my lack of prior political inclination and extreme enthusiasm. But many others were also new to this. The occupation was a baptism into leftist politics, living in community, and taking action. We organised non-hierarchically and through consensus. Banners were painted, rollies smoked. We tried to be representative and make space for every voice, though students of political theory and those with prior organising experience always seemed to know exactly when, how and what to say. There were disagreements, some small, some larger, but generally, we were united in our fight against – the factions of leftist organising only really emerging later when we tried to align on what we were for and how we would get there. I felt alive in a way I never had in my placements as a medical student. In hospital, I was stuck in a hierarchy where my presence was not only useless but annoying. In occupation, I was witnessed, useful and valued. We were united in our fight to change the world. It felt beautiful and precious.

I remember the surprise I felt, watching a documentary one evening in the Jeremy Bentham Room, that 1960’s Berkeley had been in occupation: I had until that moment thought we were the first. My ignorance of the history and politics of struggle was met with patience by lecturers, students and visitors who would embed our experience in theory. Learning felt exponential and lessons buried themselves deep. I’m grateful for the permission I had to get things wrong with no expectation that I should know it all (or anything at all); there have been few times since – perhaps in early Corbynism and parts of BLM – where entry to the left has felt so broad and accepting.

In the years of activism following my initiation in 2010, I have learnt to measure success not just on whether we achieve the outcome we’re fighting for – honestly, I would be pretty depressed if I lived by this metric – but also on the indirect impacts of our movements: Did we shift the conversation? Did we get people onboard, empower action, create community and share skills? Are we building to what might come next?

Nominally we lost, but 2010 taught us and connected us. From the immediate waves – the Really Free School to deliver alternative education in London squats, NHS Direct Action and mastering fake blood recipes to protest the Health and Social Care Bill, the Bloomsbury Social Centre, UK Uncut, and Occupy – to the ongoing ripples in Novara Media, Momentum and the fights today for racial and climate justice, what was rooted in the occupation continues to grow: shoots of seeds sown in the winter of 2010.

‘We renewed the long-dead links between our union and the campus trade unions.’

Adam McGibbon is an Irish writer and campaigner. He was the vice president of Queen’s University Belfast Students’ Union 2010-12.

Almost exactly ten years ago, the elected officers of Queen’s University Belfast students’ union sat in a meeting room fretting about what to do about the looming threat of a tuition fees increase.

We had been elected on a reform ticket – looking back on it, a relatively apolitical one – to make the union work better for its members. By the autumn of 2010, it was clear that the election of the first Conservative government of our adult lives, and the tuition fee battle that was about to start, was going to swallow up our year in elected office.

The headlines speculating about the contents of the Browne report, a long-awaited review of England’s higher education system, piled up. Part of why we didn’t know what to do was because we had come of age at a time – at least in Belfast – of widespread student disillusion. Little happened on campus politically, beyond the recruiting sergeants of the local political party youth branches. One of the union’s permanent staff members had, at the start of our term, lamented the lack of political action and put it down to the sense of powerlessness that had followed the failed anti-Iraq War marches in 2003.

Lorcan Mullen, the then deputy president of Northern Ireland’s branch of the NUS (NUS-USI), and now an accomplished trade union organiser – was at our meeting, and he fought very hard to convince us to call a union general meeting and a protest. Reluctantly, we agreed.

We called the meeting for 19 October in the union’s Mandela Hall. While postering and leafleting in the run-up to the meeting, it was clear something was bubbling – the first stirrings of outrage amongst ordinary students, not just union hacks. We expected about fifty students to turn up, and to our astonishment, got over a thousand. It was the biggest union general meeting since the dark days of 1988 – the year I was born – when the killing of Mairead Farrell, a Queen’s student and IRA member in Gibraltar had opened dark divisions on campus.

Although we naive officers had to be pushed into it, we had ignited something that hadn’t happened at Queen’s for a generation: a mass student campaign.

From that first union general meeting, things happened quickly. We renewed the long-dead links between our union and the campus trade unions. We were radicalised by the experience – although not radical enough for everyone. While the union pursued a twin-track approach of protesting and lobbying politicians, we also clashed with more militant student factions who felt we weren’t doing enough. Some of these clashes were ugly, but the approaches were ultimately complimentary. While other groups occupied university buildings, we organised larger mass protests and lobbied politicians. At one stage, we had a genuinely cross-community effort happening, with even the youth wings of the reactionary unionist parties lobbying their politicians and making convincing arguments to stop a tuition fee increase.

And students in England, even if they didn’t know it, were helping us too. Their fury, expressed at Milbank, Parliament Square and up and down the country, scared Northern Ireland politicians, who were worried about having their offices occupied or HQs smashed up.

A well-timed Northern Ireland Assembly election in May 2011 helped us continue the pressure, mobilising parents as well as students across the province. A month before the election, the DUP’s leader and Northern Ireland’s first minister, Peter Robinson, announced his party’s opposition to a tuition fee increase. The DUP were the last major party to get off the fence, and forcing them to rule out a fees increase meant that the proposal was dead and that we’d won. Although campaigning efforts continued to successfully stop hundreds of millions in education cuts and to ensure that politicians made good on their promise, that was the moment of victory.

A few months ago, I put together some research using government statistics which suggest that from 2012-18, the freezing of tuition fees in Northern Ireland has saved the country’s students £1.05bn in fees they otherwise would have had to pay. That’s huge, and the product of the collective will of thousands of students who acted to stop higher fees being imposed on those who would come after them. It is all the more impressive not only given that previous generations of students had failed to stop the imposition of tuition fees and top-up fees, but also given the Northern Ireland executive’s tendency to blindly follow the worst of English social policy. But I still await the day when higher education is free and all student debt cancelled.

The campaign radicalised me and many others. For about a year afterwards, you couldn’t walk anywhere around Belfast’s student areas without seeing the pink and yellow ‘Stop Education Cuts’ protest signs adorning student windows. Tragically, all of this is largely forgotten now, even in Northern Ireland. But this is why it’s so important that during the Covid-19 pandemic – a time in which students are organising rent strikes in their university halls and are even more precarious and indebted than they were ten years ago – today’s students remember these victories to help remind them of their huge and underestimated power.

Testimonies collated by Matt Myers.

Matt Myers is the author of Student Revolt: Voices of the Austerity Generation (Pluto Press, 2017).