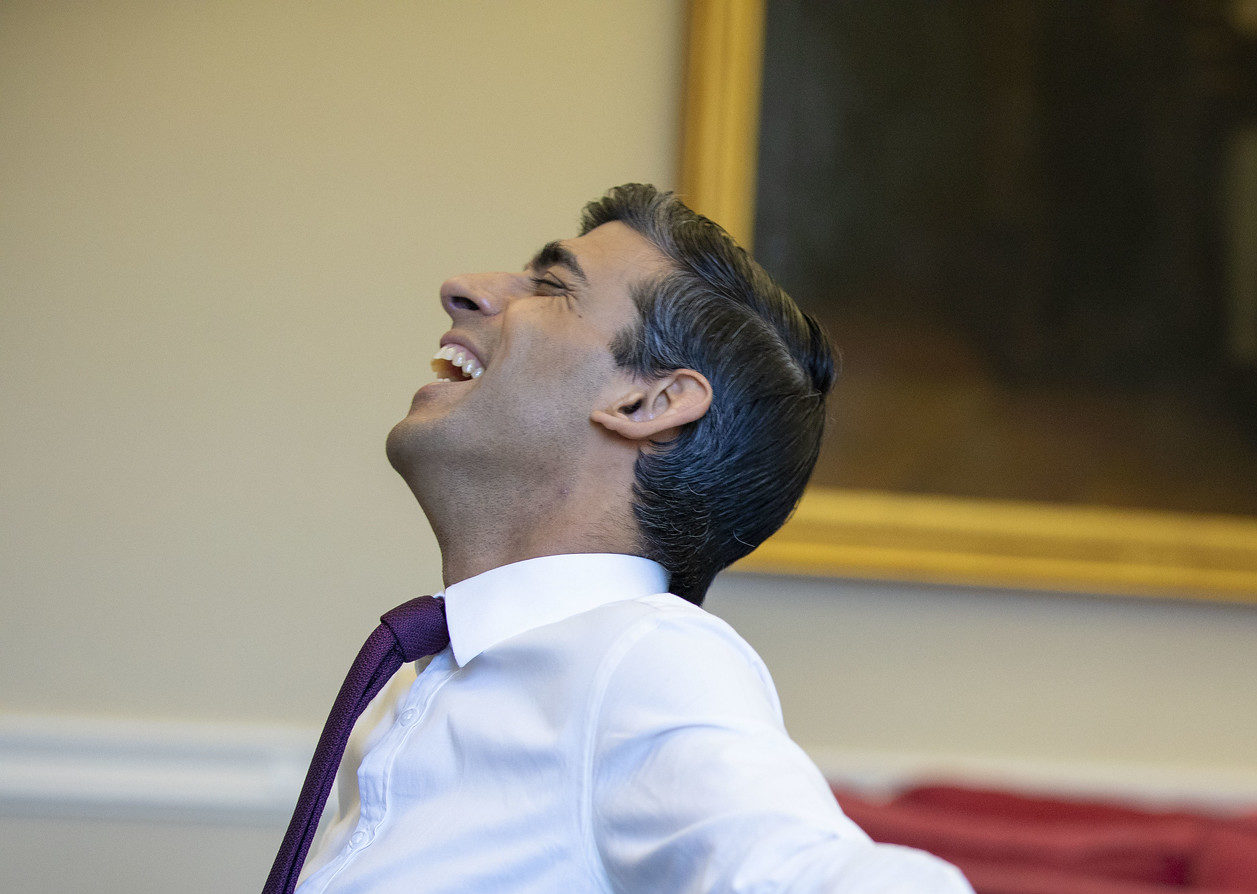

After All the Hype Over Budget 2021…That’s It?

Rishi Sunak wants to appear radical while cementing the status quo - and unless the left presents an alternative, he will.

by James Meadway

3 March 2021

Higher corporation taxes. Day-to-day spending financed by a major rise in corporation tax, big capital spending funded by borrowing. Small businesses protected with a new, lower rate of business tax. A new “UK infrastructure bank” to fund a “green industrial revolution”. Parts of the Treasury moved to the north of England, its rules rewritten to remove London bias. VAT, National Insurance and income tax frozen to protect “working people’s incomes”. Had John McDonnell become chancellor, his first full budget would have looked strikingly similar to much of the prospectus Rishi Sunak laid out today.

Let’s not get carried away, though: this is a Tory budget. The Office for Budget Responsibility reports that whilst overall spending in 2025-26 is forecast to be 41.9% of GDP – higher than the 40% it was in 2007, just before the financial crisis – the government has reduced its expected spending in coming years by £4bn (the spending review, expected in the autumn, is likely to spell out the details of where those cuts will fall). Matt Hancock’s former special advisor has already taken to Twitter to complain about the lack of commitments in this budget to increase spending on health and social care, both of which desperately need it.

And whilst the rise in corporation taxes to 25%, reversing forty years of corporation tax cuts under Tory and Labour governments, will grab headlines, the “super-deduction” will effectively hand mostly large corporations £25bn over the next two years. Sunak’s bright idea to solve the housing crisis is to sustain the housing bubble by extending the stamp duty holiday. The goalposts may have shifted, but Tories are still Tories.

The new economic consensus that this budget reflects is noteworthy, however. Nor has it been produced solely by Covid; it’s been a long time coming, with the signs there well before the pandemic. Polling has shown years of rising public support for higher taxes on those who can afford them, matched by higher public spending. Labour’s 2017 manifesto gave that public mood an organised expression, one that proved decisive in the only election since 1997 in which Labour gained seats. The problem was that the Tories soon realised they’d missed a trick. Boris Johnson, on becoming prime minister, overhauled the Conservative party in his image: pro-Brexit and pro-economic intervention. Spending increased on his watch, and the 2019 manifesto contained a raft of expensive promises. The pandemic has accelerated this trend.

This copycatting presents a serious threat not only to Labour and its leadership, but for the entire left. If you think the battle over the economy will be fought on the same terrain as that against Osborne and Cameron, you are finished. It goes without saying that we have to insist on no further cuts across public spending. We must also loudly highlight the inadequacy of existing support, with Universal Credit recipients still threatened with a sudden loss of the £20 pandemic uplift and millions of mostly self-employed still without proper support. Health and social care – especially social care – urgently need additional funding, not only to deal with the damage done during the first phase of the pandemic, but to cope with its lasting effects. Former Treasury permanent secretary Nicholas Macpherson estimates this could cost as much as £50bn, a figure the Tories’ plans do not even approach.

Was obvious from 2017 election result (and years of polling beforehand) that the economics Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell stood for was broadly popular. Danger for Labour was always that Tories would realise this. And now here we are. #Budget2021

— James Meadway (@meadwaj) March 3, 2021

We must also think bigger than demanding more support for the things we already have. Moments of crisis present huge political possibilities, and now is one such moment. We must not simply demand a recovery; left to its own devices, the economy will recover, pretty much regardless of what the government does. No, our task now is not to make that rebound occur so much as to ensure that it takes the shape we want it to.

The Tories have grasped this since at least September, and while much of their talk may be opportunistic, they have the political incentive and capacity to deliver on at least some of the “green industrial revolution” and “levelling up” of which they are so fond of speaking. If there is not a clear alternative, their version of recovery will win out.

Tragically, Labour is not offering that alternative. Shadow chancellor Anneliese Dodds is right to oppose spending cuts; highlight Tory corruption and insist adequate protection be provided to all who need it. But it’s not enough to get in front of the Tories who, as things stand, could well forge a new political hegemony in England, perhaps for the next decade or longer: a post-Brexit, Red-Green Tory future of the kind Teesside mayor Ben Houchen envisions.

NEW: Greater Manchester mayor @AndyBurnhamGM describes the budget as “a packet of Polos”

He commends the Chancellor for many of the announcements, but describes the lack of additional support for areas like NHS and social care as holes in the Budget (like polos)

— Nadine Batchelor-Hunt (@nadinebh_) March 3, 2021

But having a vision doesn’t just mean telling everyone how nice things should be. It means having a plan for how justice will be enacted – or, more prosaically, who will pay for the nice things. This is why it was an error for Labour to oppose the corporation tax rise: it meant letting the Tories make a claim on justice, leaving Starmer in the role of technocratic manager of the status quo.

The pure economics of the corporation tax increase are, in any case, disputed: a well-known result in conventional economics shows that tax rises matched to equal spending increases are expansionary overall since they promote more spending. Anyway, UK corporations have built up a £900bn hoard of unspent funds over the last decade or so – they are hardly the biggest spenders out there. Corporation tax changes have little economic impact either way. The Institute for Public Policy Research has very usefully offered a range of different tax changes that could create a more just economy in the future.

What should the vision look like? Justice must be part of it: stating clearly who will pay for what. If Labour can’t manage this, it will continue to struggle. It is notable that Sunak was so unabashed about his tax increases. Again, this appears borrowed from 2017, when Labour majored on tax rises for higher earners as a way to win public trust and credibility for future spending. Sunak will have different reasons for so noisily broadcasting this policy, most likely his plans to just as loudly reverse tax rises later. We need, too, some clarity on the kind of additional spending needed across the public sector to cope with the long-term impacts of Covid-19.

Just as urgently, we need a vision of the economy beyond what the government is currently doing: how jobs can be created and sustained; how our assets, from our data to our businesses, can be run more equitably; how adaptation to a changing planet can be implemented fairly; how the recent changes to our lives, including increased homeworking and reduced international travel, can be made to work for all of us. The next few years will shape the next decade. The Tories understand this. So should we all.

James Meadway is an economist and Novara Media columnist.