Being an Opportunist Has Worked Well for Johnson. Why Not for Starmer?

A year on from winning the Labour leadership, Starmer has now lost all momentum.

by Samuel Earle

3 April 2021

Keir Starmer was elected as Labour leader on a wave of sober, grown-up excitement. According to popular opinion, he was Boris Johnson’s antithesis: serious, meticulous, well-groomed – an honest and principled leader who would reveal the Tory prime minister for the bumbling clown he is. A pandemic would provide a grimly ideal setting, making the sharp contrast in character between the two leaders all the more clear. The Tories would rush to form a national government with Labour, some said, simply “to spare them Starmer in opposition”.

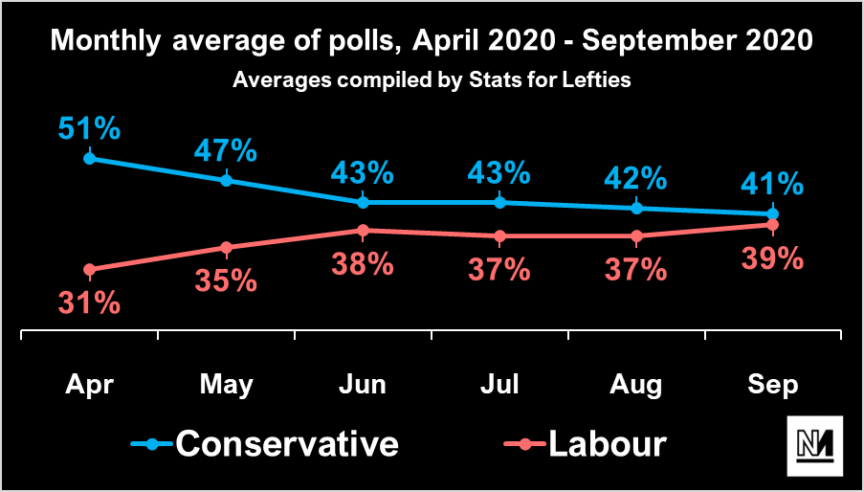

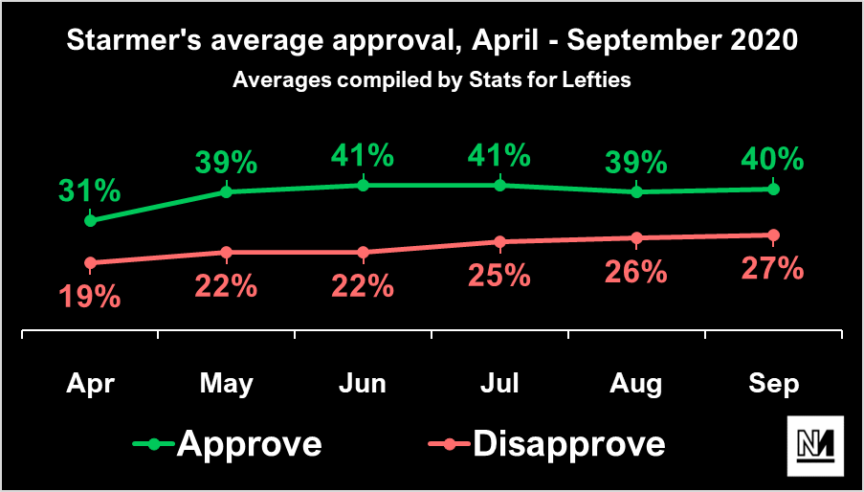

In his first few months, such fantasies could be indulged. Between April and September, Labour drew level with the Tories in the polls. As Johnson floundered and Britain’s death-toll mounted, Starmer’s stature grew. His approval ratings grew to levels not seen by a Labour leader since the 1990s. Columnists gushed over his “forensic” abilities, while lamenting a world that could have been. “With his forensic skills, Starmer could have torn apart the flimsy case for Brexit and laid bare the lies,” Martin Fletcher, former editor of the Times, wrote in May 2020.

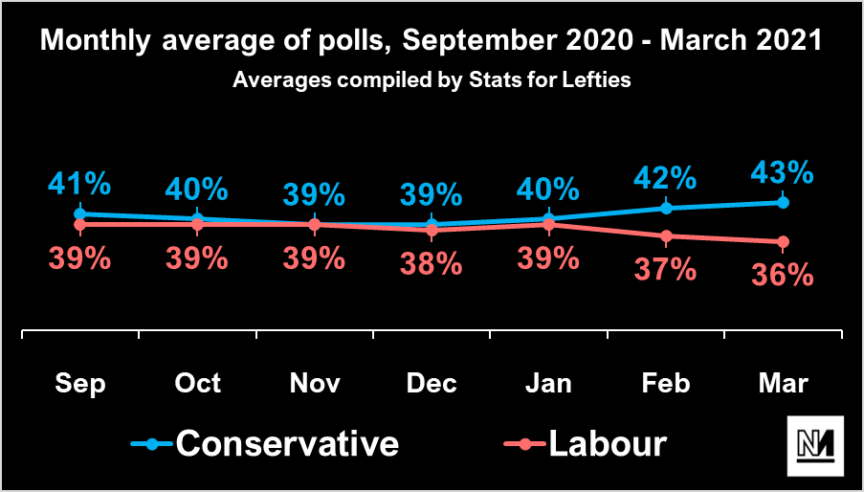

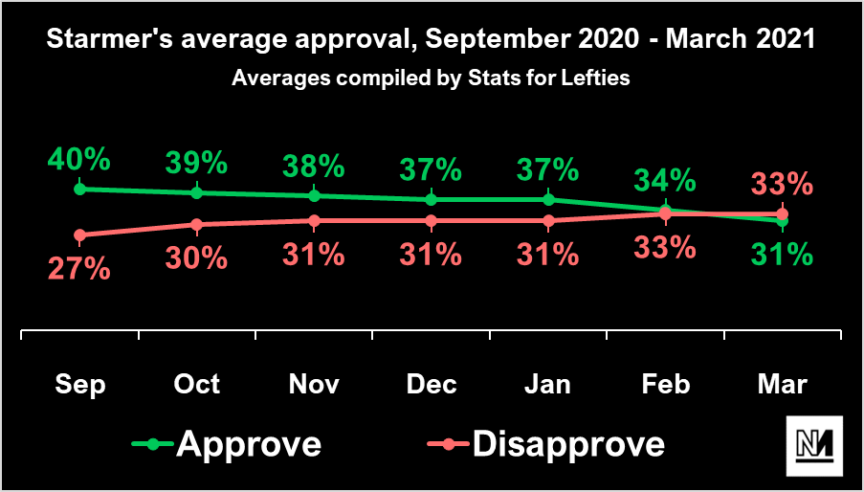

But on the first anniversary of winning the Labour leadership, Starmer has now lost all sense of momentum. After over a year of blatant and repetitive government blunders and more than 150 000 deaths, Johnson’s Tories are comfortably ahead in the polls again. Starmer’s own popularity has nose-dived – more voters now disapprove than approve of him, with a sharp shift among both Labour and Tory voters. The original narrative has been revised. The pandemic, far from ever offering Starmer an opportunity, was now always going to be an impossible obstacle: who cares about party politics during a national crisis? With the government’s recent vaccine success, of course Starmer is falling further behind.

Yet these explanations distract from Starmer’s very obvious failings. An incoherent strategy has earned him a reputation for vapidity that will be hard to escape. He’s called himself a “socialist” and then, after following in the Tories’ footsteps for almost a year, chose to oppose them on raising corporation tax. He’s a former human rights lawyer who seemed set to abstain on the policing and crime bill curtailing the right to protest, before public outcry led him to vote against it. He’s an opportunist seizing all the wrong opportunities. Even his staunchest supporters are wondering: what does Starmer stand for?

For Johnson’s ostensible antithesis, this is a very Johnsonian question for Starmer to be answering – after so long in the public eye, few can say what Johnson really thinks either. It speaks to an emerging likeness between the pair. In many respects, what Starmer and Johnson share – albeit to different extents – is a lack of political conviction: they both claim to be politicians motivated by a consistent set of principles, and yet act more like empty vessels for whatever’s deemed politically expedient at the time.

Johnson is obviously the more egregious example: there is no avowed belief that he may not betray later down the line. His convictions are like crutches, carrying him to the next career goal where they can be replaced with new ones. But the problem for Starmer is that Johnson is also the better actor: Johnson’s beliefs are more believable than Starmer’s, even if they are held more cynically. Johnson brandishes his inconsistencies as the vacillations of an authentic personality – he’s a man who wants it all – whereas for Starmer, they simply suggest a bad PR strategy: he doesn’t know what he wants at all.

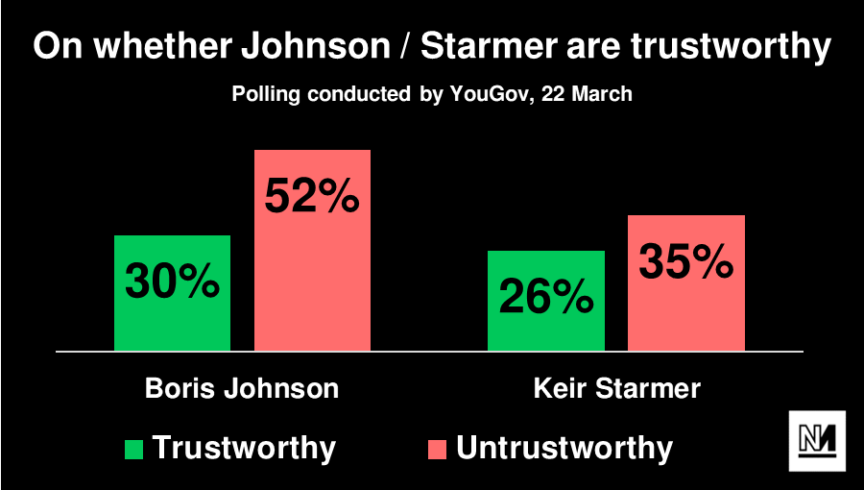

This helps to explain why a quality Starmer and Johnson share – opportunism – is a weakness for one and a strength for the other. Whereas Starmer is chronically nervous about saying ‘the wrong thing’, such that in interviews he hardly says anything at all, Johnson couldn’t care less about saying the wrong thing: he appears, at least, to speak his mind. The result is to make Starmer seem even more suspicious, more establishment and less trustworthy than Johnson – perhaps the most establishment and untrustworthy politician there really is.

There should be no denying that Johnson is a formidable political opponent, especially in such a Tory-friendly media environment. At a time when most British politicians seem bland and one-dimensional, Johnson has mastered the art of holding multiple identities at once – a man of so many masks that, one stacked upon the other, they have granted him an illusion of depth. He has played the libertarian and the authoritarian, the wartime leader and the classroom clown, the man of the people and the aristocrat. And yet Johnson is genuine in his deception: he’s been lying his whole life; it’s who he is.

In a 2018 study, “The Authentic Appeal of the Lying Demagogue,” a team of sociologists explored this phenomenon. They found that in contexts where levels of trust in politics are low – and in Britain they are at their lowest in decades – a politician who performs their duplicity openly can be perceived as authentic. Because all politicians are liars, the one who lies brazenly is the honest one, as they are acknowledging what a pantomime politics really is. Smooth technocrats, by contrast, fare badly: they think they can take voters for a ride.

Starmer, having appointed several Blairite aides to senior roles, seems to be pursuing this doomed model. He appears before the electorate as one of those wooden politicians – formulated in focus groups, hollow at the core – who Johnson mocks by his mere presence. Where Jeremy Corbyn’s appeal was premised on his historical record, Starmer’s claim is less grand and more pragmatic: he’ll always be on the right side of the news story, rather than history. This is what’s called ‘competence’ and, partly because it requires no radical policy positions (or indeed any policy positions at all), it has earned Starmer some positive press coverage. But Starmer’s plummeting popularity shows what a precarious and futile strategy it really is: it’s only a matter of time before you put a foot wrong, and once you do it’s not clear what track you were even on.

In the heady days of Starmer’s rise to Labour leader, Jon Trickett appears to have told both Prospect magazine (anonymously) and the Observer (on the record) the same revealing anecdote about Starmer. “One of the things I have noticed about Keir is that you can be walking through the Commons, or wherever it is, with him in a reasonably comradely way and then, suddenly, he would end up two strides ahead. It is just how he is.”

A year on and Starmer seems, at best, two steps behind, and at worst, lost. Hopes for his leadership have collapsed into a mounting heap of excuses: the pandemic has protected Johnson (despite his prime ministership being a national disaster); a vaccine bounce has lifted the national mood (even if Starmer was struggling before the rollout success); an “inexperienced” shadow-cabinet has failed to communicate the message (without any sense of what the message is); and so on.

Yet the sheer proliferation of justifications warns of a deeper problem. Perhaps Starmer should start with some introspection. Wrapping himself in the union jack and wrestling the Tories for ‘red wall’ voters ventriloquized by journalists at The Sun, Starmer is dancing to Johnson’s drum. Is this why he wanted to become Labour leader? Even his own shadow cabinet are complaining of a “lack of direction”. Labour voters will have to hope that this is not “just how he is.”

Samuel Earle is a writer based in London. His work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, the London Review Books and elsewhere.

Part one in this series on the Tories and how they hold on to power can be found here: Even Without the ‘Vaccine Bounce’, Boris Johnson Would Still Be Winning