Proportional Representation Won’t Solve All the Left’s Problems, But We Should Back It Anyway

Whatever the system, Labour needs to win more votes.

by Ell Folan

12 May 2021

Eleven years ago this month, protesters gathered outside Lib Dem HQ and called on the party not to join a Tory-led coalition without an agreement to introduce proportional representation (PR). What we got instead was a failed referendum on constituency-based preferential voting. After the referendum, I expected the issue of PR to disappear. It didn’t.

In recent years, 214 constituency Labour parties have backed reform, along with multiple trade unions, Andy Burnham and a majority of Labour members. Supporters argue that PR would keep the Tories out of power, and would reflect how people actually vote.

Much of the discourse around PR focuses on mathematics and neglects to discuss political realities, such as the question of who the Lib Dems would support in practice and the fact that rightwing parties would benefit too. Having said that, PR would accomplish two objectives: it would prevent the Tories from winning even if they lose the popular vote (as they did in 1951), and it would ensure that retired conservatives in a handful of marginal seats no longer have a veto over politics.

What would UK elections look like under PR?

Under the UK’s current voting system, first-past-the-post (FPTP), the UK has 650 constituencies, electing one MP. Whoever wins the most votes in a constituency becomes the MP.

There are lots of alternative systems. The Single Transferable Vote (STV), a preferential system, is used in Northern Ireland; the Additional Member System (AMS), which combines constituencies and proportional party lists, is used in Scotland, Wales and London; and party-list PR was used for EU elections from 1999-2019.

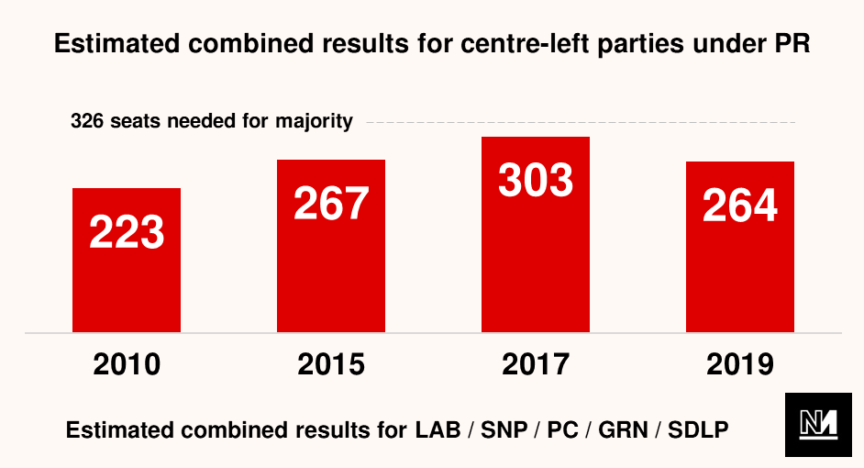

The table below shows what the UK seat results would have been since 2010 if party-list PR had been used.

PR is not a miracle cure.

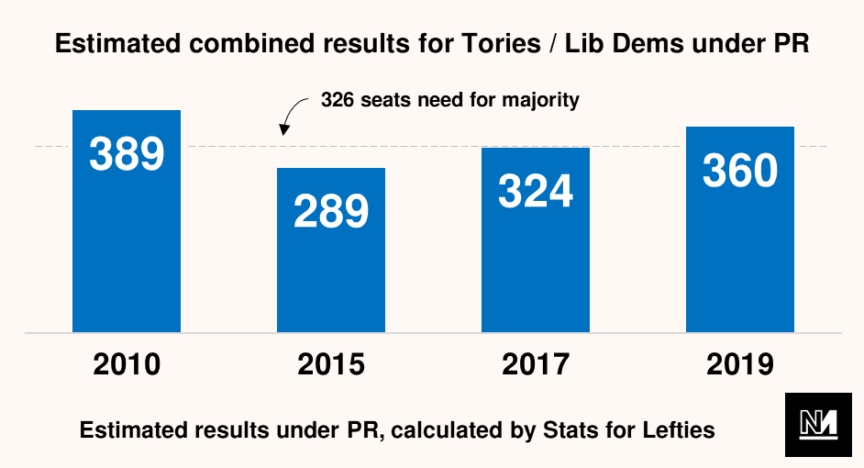

As the charts above show, the Conservatives would not have won a majority under PR in any of the past four elections. Many supporters of PR argue that the system would thus mean an end to Conservative government. But as you can see in the graph below, centre-left parties would not have won a majority either.

In practice, the big question of PR is: what would the Lib Dems do? As we’ve seen over the past decade, when offered the choice between a Labour-led government and a Conservative-led government, the Lib Dems will back the Conservatives. And my estimates suggest that a Tory/Lib Dem coalition would have had a majority in 2010, 2017 and 2019.

While PR would benefit leftwing parties like Labour, it would also benefit rightwing parties. Ukip, which won just one seat in the 2015 general election, would have won 79 seats under PR.

In short, it would be a mistake to assume that PR would automatically lead to a Labour-led government. 2010, 2017 and 2019 would have left the Lib Dems holding the balance of power (and they tend to back the Tories); the 2015 election, meanwhile, would have resulted in an overall majority for rightwing parties. Only 2017 – when Labour won 40% – would have resulted in the left being close to forming a government (the left would have been just 19 seats short of a working majority).

Ultimately, no matter what the system is, Labour will struggle to form a government in Britain without winning a substantial number of votes (ideally 40% plus).

First-past-the-post holds the left back.

However, FPTP does disadvantage the political left, and it is still worth changing the system. Since Labour was founded, the Conservatives have won a clear majority on less than 50% of the vote a total of thirteen times. Labour has done so just five times.

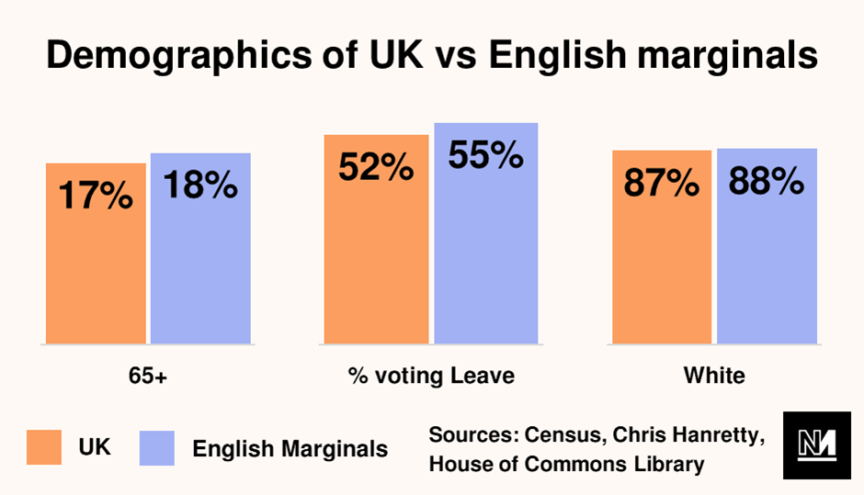

But FPTP holds the left back in other ways too. Because marginal constituencies in England determine who forms the government, politicians focus on appealing to voters in these areas. And at the moment, the most marginal constituencies in England (i.e. majorities of less than 5%) are on average older, more pro-Brexit and whiter than the rest of the country.

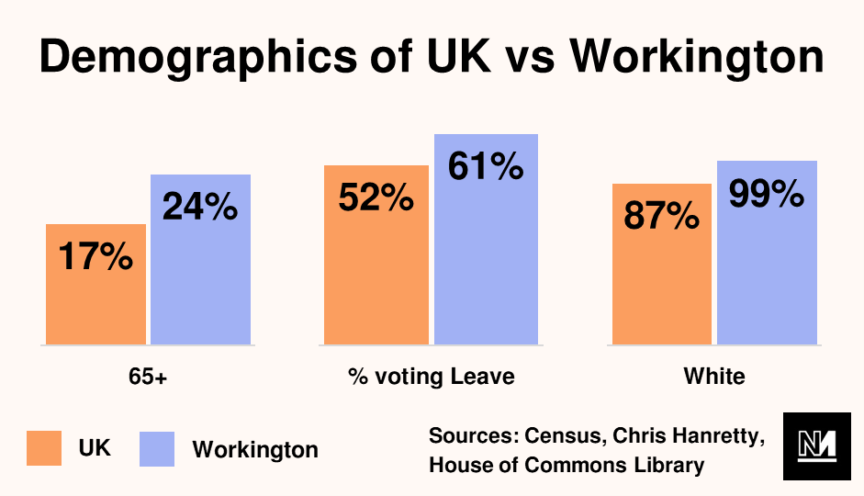

As a result, leftwing policies that are popular with the majority of voters end up being vetoed by a small minority of socially conservative retirees who happen to live in the most marginal seats. For example, one key constituency that helped determine the 2019 election was Workington: a seat that is substantially whiter, older and more pro-Brexit than the rest of the country.

But perhaps the most concerning impact of FPTP is that it allows a party to win an overall majority of seats even whilst losing the popular vote. This is, famously, what Donald Trump achieved in the 2016 US election; but it also occurred in the UK in 1951 (Conservative victory) and in England in 2005 (Labour victory). My seat estimate model currently suggests that Labour would still come second in terms of seats in 2024 even if it won the popular vote by 1-2 points.

Last week’s elections, which saw Labour lose in Hartlepool, Tees Valley and the West Midlands, suggest that the party is falling far short of winning the 40% plus that it needs to form a government. Given this context, it is unsurprising that many Labour activists are focusing on PR.

As I have demonstrated, PR is not a magical solution. PR would strengthen rightwing parties too, as well as resulting in Tory/LD coalitions most of the time. However, PR would prevent the Tories from winning majorities and would allow Labour to focus on appealing to the whole country.

I think that PR would be the better system, both for the UK and for Labour. But I also think that focusing on systems, instead of on developing policies, would be a mistake. Whatever the system, Labour needs to win more votes than in 2019. I hope this is what Labour focuses on.

If not, we can expect to see more defeats like Hartlepool in 2024.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties and a columnist for Novara Media.