Don’t Believe the Bigots – Trans Rights Aren’t a Threat to Women

The efforts of those in power to demonise marginalised communities make it harder to see things clearly.

by Ash Sarkar

15 June 2021

Like a lot of people, getting my head around trans rights – access to healthcare, access to public space, protection from discrimination – wasn’t necessarily instinctive. At university, fuelled by an undergrad’s sense of righteous certainty when it came to race, class and a clumsy kind of feminism (‘being a girl is kind of hard, but also awesome and powerful???’) transphobia was almost invisible to me. I was ambiently aware of the existence of trans and non-binary people, but what that might mean in terms of institutional and interpersonal discrimination may as well have been molecular biology: sure, it’s important to somebody, it’s just not for me to think about. And as with most sins of obliviousness, it turned occasionally into unkindness.

I airily waved away a petition in support of providing more gender neutral toilets on campus, unable to even imagine that between me and the guys whose aim rapidly deteriorates after the second pint was the right of trans and non-binary people to go to the loo without fearing harassment or worse. But it gets harder to maintain a determined state of not-knowing when you share a bit of your life with someone who’s directly impacted by the consequences of your callousness. I became friends with a trans woman after she was the only person to stick up for me in a feminism discussion group for trying to talk about race and class to an audience of hideously bourgeois humanities students. It’s not like she sat me down and gave me a seminar in Trans Rights 101; that’s not a fair expectation of anyone from a marginalised group, and in any case, I probably would have said something boneheaded and extinguished any hopes for friendship we might have had.

But simply hanging out (deciding where to link up on campus or which cafe to gossip in) got me to see a bit of what I’d been excluding from my field of vision. It was implicit rather than anything that had to be said out loud, but we found ourselves meeting mostly where there were gender neutral toilets. We didn’t go to football pubs. Trans people aren’t teachable moments for clueless cisgender heterosexuals, but through the quotidian stuff of being mates, I started to understand a little of how institutional exclusion and the fear of transphobic violence shaped my friend’s life.

There was an invisible map of trans-friendly infrastructure, and a sense of where might not be safe to go – and these considerations regulated where she could go. Being trans didn’t exist in a separate universe from how I experienced gender: it was like there was an extra layer of decision-making on top of the fraff we both shared as women, like routes home after dark and keeping an eye on your drink. I felt embarrassed of how ignorant I’d been before, of all the myriad ways I’d participated in making the lives of people in a marginalised group more difficult. I know being supportive of trans rights when you’re not yourself transgender is often scoffed at by its detractors as ‘virtue-signalling’, but what’s wrong with that? I’d spent a lot of time signalling that I was an arsehole.

The narrative that pits “women” against transgender people perpetuates the myth that trans people – in particular trans women – are predatory and threatening.

– @AyoCaesar on #TyskySour pic.twitter.com/JljUn1fE3G— Novara Media (@novaramedia) June 30, 2020

Over time, I learned that the exclusion of trans and non-binary people goes far beyond toilets and changing rooms: it’s at the heart of all the other issues I derived my political identity from caring about. A quarter of trans people have experienced homelessness at some point in their lives; one in eight trans employees have been physically attacked by colleagues or customers in the last year; 40% of trans people, and over half of all non-binary people, adjust how they dress to avoid discrimination or harassment. It’s become fashionable amongst both the opportunist right and the reactionary left to frame trans issues as oppositional to ‘real issues’ faced by ‘real working class people’. But from domestic violence to workplace rights, there isn’t an area of social or economic justice, which doesn’t also touch on the lives of transgender people. Just by expanding my reading a bit, I realised how limited my politics was in its failure to acknowledge the impact of institutional transphobia on people’s lives.

In the past 12 months, 16% of transgender women have experienced domestic abuse by a partner.

For ‘feminists’ to insist that refuges and rape crisis centres should actually exclude one of the most vulnerable demographics to this particular form of violence is utterly shameful.

— Ash Sarkar (@AyoCaesar) March 3, 2020

There are a lot of people on telly and on the internet who’ll tell you that this process of learning is impossible. Rightwing talking heads disdain the idea that anyone can authentically care about anything at all: addressing trans and non-binary people by their preferred names and pronouns is at best progressive posturing, and at worst a grotesque infringement on freedom of speech. This position, frankly, is as weak as Laurence Fox’s singing voice. Whatever you might think of gender and its relationship to biological sex, the right to free expression does not override the rights of trans and non-binary people to live free of harassment or discrimination. Genuine mistakes are one thing, but deliberate deadnaming and misgendering (i.e. calling someone their pre-transition name, or referring to them by anything other than the gender they identify as) is a way of asserting your control over someone. It’s saying that ‘I have more power to determine who you are than you do; I can curtail your freedom to live authentically at any time.’

It is testament to many people in the newspaper industry’s lack of self awareness that they don’t realise their industry is dying and anti-trans bullshit is actively alienating to the potential younger readership they badly need

— shon faye. (@shonfaye) June 7, 2021

But there are also those who exclude transgender people – in particular, transgender women – in the name of feminism. There are a variety of purported justifications for this, from the idea that transgender women pose a threat to cisgender women in spaces like public bathrooms or changing rooms, to believing wombs determine gender and that’s all there is to it. At the heart of the so-called ‘gender critical’ perspective is an insistence that the rights of cisgender women and the rights of transgender people are irreconcilable: that somehow, the right of my friend to live as who she is takes something away from my safety and selfhood. But the handful of trans people who have posed a threat to others is far outweighed by those who have been victims of abuse and discrimination; indeed, most feminists would cry foul were the actions of a minority of female abusers used to detract from the pervasive problem of violence against women.

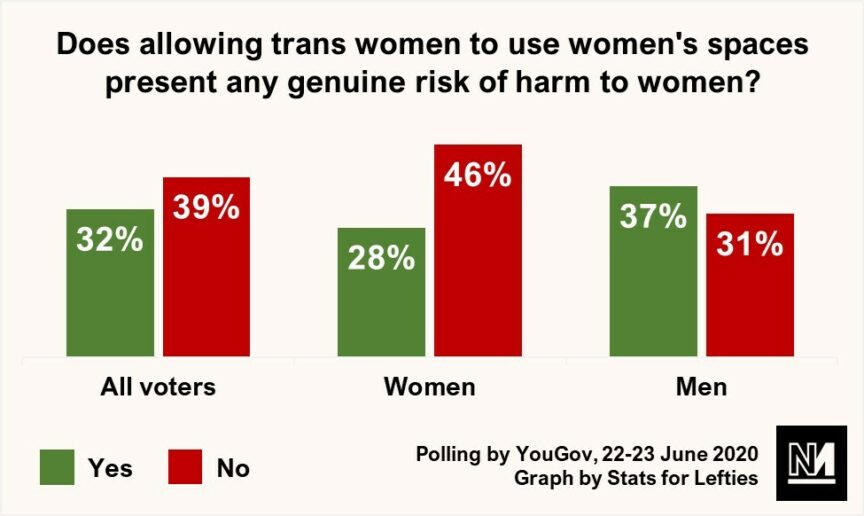

Nobody is born knowing everything about politics, and indeed, the concerted efforts of those in power to demonise marginalised communities make it harder to see things clearly. The overrepresentation of unsympathetic or even bigoted voices in the media means that we’re denied a realistic view of issues facing trans and non-binary people (as Shon Faye notes The Times and The Sunday Times wrote nearly 300 articles about trans people in 2020 alone, almost all of them from a hostile perspective). But despite the prevailing narrative in trans-hostile media, more women than men are likely to accept a trans person’s chosen gender, and it’s men who are more likely to believe that allowing transgender women to use female facilities would put women at harm.

The fact is that trans people and cisgender women have more in common when it comes to vulnerability to patriarchal violence than they have opposing interests – and most women recognise this.

Ash Sarkar is a contributing editor at Novara Media.