Universal Credit Is a Symptom of Britain’s Broken Jobs Market

People on UC have jobs, they're just crap ones.

by Andrew Fisher

9 July 2021

The government has announced its plans to cut £1,000 from the annual income of six million households on universal credit this autumn, despite the fact that many receiving the benefit are already living below the breadline.

The decision, which the Child Poverty Action Group has estimated will push more than 300,000 more children into poverty, shines a light on the precarious, degrading and fundamentally inadequate nature of the UK’s social security system.

During the pandemic, the universal credit benefit was made marginally more humane when the demeaning and punitive sanctions regime was halted, and a temporary uplift of £20 per week was introduced.

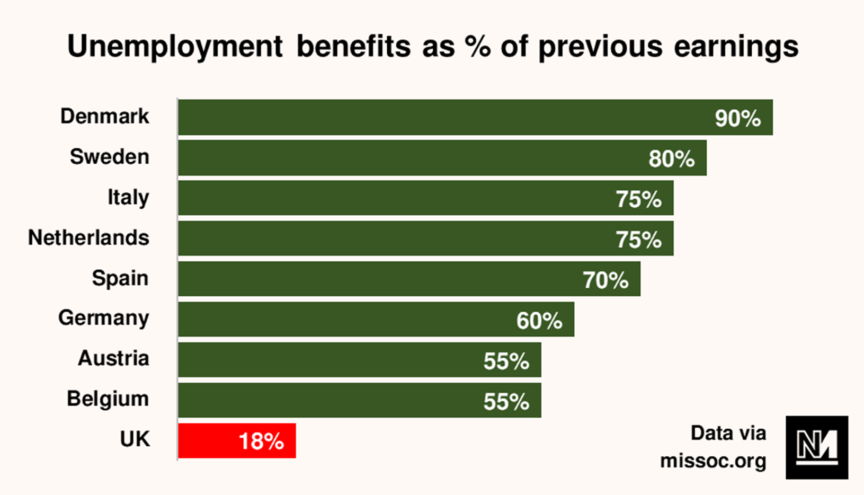

That said, a £20 increase is by no means enough to lift people out of poverty, with the standard rate of benefit increasing from just 14% to an only slightly less meagre 18% of average earnings. Compare those figures to the rest of western Europe, where unemployment benefits are generally worth over half of a person’s previous income, and it becomes clear that the UK’s social security system is seriously lacking.

Case in point: in Ireland, if you lose your job and apply for social security, you’ll most likely get around £183 per week; in the UK, it’s just £74 – although with the temporary uplift, that figure has risen to £94.

Coincidentally, at the start of the pandemic, the then health secretary Matt Hancock was asked if he could survive on statutory sick pay (SSP) of £94 per week. In an uncharacteristic display of honesty and openness, he admitted he could not. Despite Hancock’s admission – coupled with the fact that the country was in the grip of an economically fraught global pandemic – the SSP benefit was not increased, instead remaining at a level that government ministers themselves conceded a person could not survive on.

As a result of such inadequate support during this time of crisis, thousands of workers weren’t able to afford to self-isolate and were thus forced to drag themselves into work. What’s more, millions of low paid and self-employed workers were excluded from claiming SSP at all.

The temporary £20 top-up only applies to those on universal credit, excluding the nearly two million disabled people who receive Employment and Support Allowance – the basic rate of which is only £74 per week.

Universal Credit isn’t just an unemployment benefit, it’s not just a in-work topup benefit either.

Barely anyone has mentioned it’s the main income for hundreds of thousands of disabled people unable to work.

They can’t just get a job.

— Alex Tiffin (@RespectIsVital) July 7, 2021

In a rare bit of policy clarity – and to the credit of shadow work and pensions secretary Jonathan Reynolds – Labour has said that the £20 top-up should be made permanent and extended to those on legacy benefits.

Good morning. I am still smiling today but will shortly be on your TV to tell you that the UK has more households in receipt of Universal Credit who are about to lose £1000 a year – 6m – than the entire population of Denmark (5.8m)

I say #ItsComingHome but let’s #cancelthecut pic.twitter.com/mbFvHOJquT

— Jonathan Reynolds (@jreynoldsMP) July 8, 2021

But this is only the first step in creating a social security system that actually provides genuine security. For all the talk of a new Conservative philosophy under prime minister Boris Johnson, who declared the end of over a decade of Tory austerity, the government maintains a harsh and punitive approach to social security.

In February 2021, in the midst of a nationwide lockdown, 200,000 families had their benefits capped – that’s 122,000 more than at the same time in 2020, just prior to the pandemic. Any spike in post-pandemic unemployment is likely to usher in a new round of social cleansing; as universal credit is capped, people will be forced out of their homes into cheaper parts of the country.

Johnson has attempted to distract from the brutal reality of the Tories’ social security regime by appropriating the language of progressive movements, declaring his intention to “build back better“. But after years of broken promises, it’s become increasingly clear that this is the stuff of fantasy.

The @G7 showed that the world’s democracies are ready and able to address the world’s toughest problems.

We have solutions to defeat Covid, minimise the risk of another pandemic, and build back better, fairer and greener, for the benefit of all. pic.twitter.com/SgeCK0ydfn

— Boris Johnson (@BorisJohnson) June 16, 2021

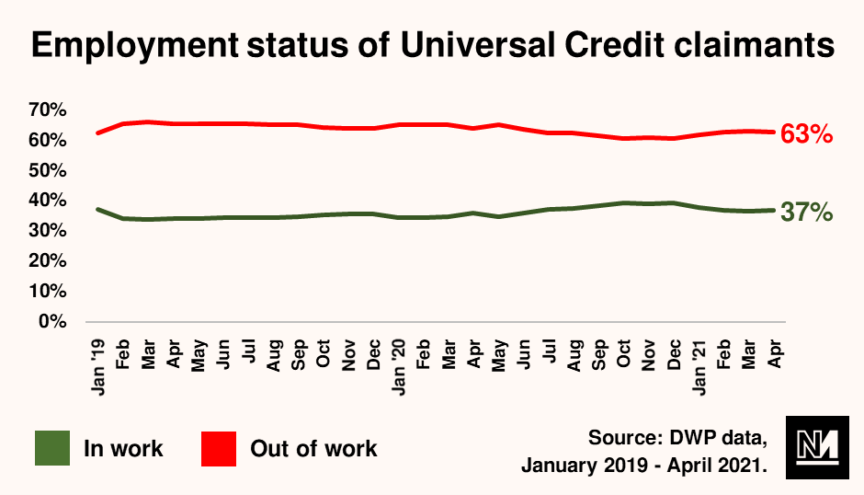

When asked by MPs earlier this week about the potential for making the £20 uplift permanent, Johnson replied: “If you ask me to make a choice between more welfare and higher paid jobs, I’d choose higher paid jobs”. Indeed, if you ask unemployed people if they’d like to live on £74 per week or have a highly paid job, they’d say the latter too. This, however, is a false dichotomy, not least because 37% of people on universal credit are in work – and only claiming benefits to top-up low pay and insufficient hours.

This, of course, is the Conservatives’ doing. The current Tory government has not only cut social security, but overseen a rise in low paid, insecure work. There are now more than a million workers on zero-hour contracts, up 20% in the last five years alone.

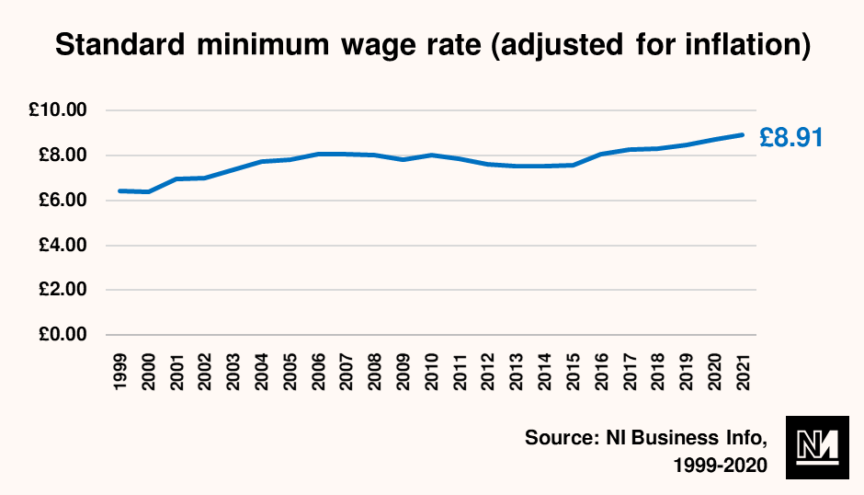

In 2015, the then chancellor George Osborne promised a £9-an-hour minimum wage by 2020. It’s now 2021 and the minimum wage is still below that level, at just £8.91 – and even then that’s only for over-25s.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak was dispatched to TV studios yesterday to echo the prime minister’s spin. “The best way to help people is to help them into work and then to make sure those jobs are well paid,” he told a depressingly credulous media.

But universal credit is paid to millions of workers precisely because too many jobs are low paid with insecure hours. One in every eight workers is currently living below the poverty line – an increase of two million people since 2010.

And so much for that other Johnson soundbite about “levelling up” prosperity outside of the South of England. The £20 cut in universal credit will disproportionately impact those in the Midlands and the North, affecting one-third of households, compared to the one-fifth it will affect in southeast England.

Cutting the £20 uplift exposes the government’s empty rhetoric and is a kick in the teeth for millions of people in the UK. That said, even if the uplift was to remain, it would still be insufficient in terms of actually helping people out of poverty.

Indeed, if the government is actually serious about that (spoiler: it’s not), there are three things it would do:

1. Strengthen the UK’s trade union rights – the most restrictive in Europe – and allow workers to organise effectively to push up wages.

2. Cap rents to stop workers’ wages subsidising the property portfolios of corporate landlords.

3. Introduce a minimum income guarantee to ensure no one was left in poverty, whether they were in or out of work.

These are simple, moderate demands that will help provide genuine social security in a country marred by rising levels of poverty and low pay, thanks to a deregulated labour market. It is vital we make these demands a new common sense: in our workplaces, our communities, our unions and in the Labour party.

Out of the rubble of World War II, with the country in twice as much debt as it is today, that government really did build back better, creating the NHS, a social security system and a mass council house building programme. Where Clement Attlee had ambitious and liberating policies, Boris Johnson and his government have only empty and divisive rhetoric.

Andrew Fisher is a freelance writer and policy consultant. From 2016 to 2019 he was the Labour party’s executive director of policy.