Generation Left Might Not Be That Left After All

16-24-year-olds want spending cuts over tax increases.

by James Meadway

22 July 2021

However dire the situation has looked for the British left since the 2019 general election, young people’s unwavering support has served as a real beacon of hope.

Indeed, “Generation Left” – a term coined by sociologist Keir Milburn to describe those born roughly since Margaret Thatcher’s first election in 1979 – seem to be united in their support for a more socialist kind of politics, overwhelmingly backing the Labour party in successive elections, and seemingly being deeply opposed to capitalism. A new report by the free market Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) revealed that 75% of those under the age of 40 specifically blame the capitalist economic system for climate change and the housing crisis, amongst other social ills. Judging by this research, anti-capitalist beliefs and attitudes seem to be remarkably strong amongst younger people in Britain.

Despite the rightwing media’s despair at this apparent insurgency of “Millennial Socialists”, it would be a dangerous illusion for the left to take these reports at face value. Generation Left’s commitment to the ideas and programmes of the left rests on rocky foundations. In understanding why, we should look to Milburn’s account of how this group was formed.

According to Milburn, the seeming commitment of Generation Left to socialist ideas is a consequence of their experience of the economy over the last decade – an experience in which the 2008 financial crisis played a vital and devastating role. While homeownership – a key factor in people’s economic security – peaked just before the crash, the aftermath was a horror story: wages plummeted (furthest for young workers) and zero-hour contracts exploded. Over a decade later and the average pay rate has still not recovered to its pre-crash level. House prices, on the other hand, have continued their upward march, meaning that many people now have even less money in real terms but it’s even harder to buy a house – and young people have of course been hit hardest by this.

Young can’t afford to get on housing ladder, have huge amounts of debt, will rent longer than ever, can’t save for pensions or having kids, have endured a 10 year economic downturn & won’t enjoy same welfare state as parents & grandparents.

Defend our young people @Keir_Starmer!

— Aaron Bastani (@AaronBastani) July 16, 2021

Where we might typically view the divides in attitudes between the young and old as ‘generational’ and related to age, Milburn argues that such a divide is, in reality, a reflection of class and how it has changed in Britain. This new, young working class, who entered the post-crash labour market, have been deprived of much of the material security that their older counterparts enjoyed – like secure housing, or secure work. This also applies to very large numbers of younger workers who went to university. With 50% of 18-year-olds attending university, education is no longer a marker of class in the way that it was two or three generations ago.

Milburn’s description of how age and class relate to one another is a world away from the usual, superficial accounts of the generational divide, which mistake having a university degree for being middle class, or imply that millennials are idealistic youths – the oldest are now entering their forties, with families of their own. Having a proper understanding of this relationship is essential to understanding of Britain’s political landscape today.

Shit material conditions don’t equal socialism.

There are two conclusions we might draw from the emergence of Generation Left. The first is more optimistic: since capitalism is failing to deliver for most young people and arguably shows no real prospect of being able to do so in the near future, their continued support for the left is all but guaranteed. By this logic, over time, young people will end up comprising the majority of the population and will thus dominate and shape the political future.

The views of “Generation Left” are “a preview of what will be the mainstream opinion in Britain tomorrow.”https://t.co/jqdaZY3l3H

— The London Economic (@LondonEconomic) July 12, 2021

The second conclusion, however, offers a much bleaker picture. If Generation Left’s anti-capitalist attitude is rooted in material experience, then there is no reason to think that their experience of capitalism alone will lead them towards embracing left-leaning politics. They could recognise how bad things are for themselves, but draw decidedly anti-left conclusions. Think, for instance, of the different ways in which someone might understand why they are unemployed. You could argue that the reason you can’t get a permanent job is due to bosses chasing profits at the expense of their workers. But you could also argue that it’s because there are too many migrants. Both arguments offer an explanation for these material conditions. Sure, one is rooted in fact and one is totally unsubstantiated, but there is no guarantee that from material conditions alone a person would reach the sensible conclusion. The last two hundred years of capitalism ought to tell us that economic circumstances alone are no guarantee for socialist politics.

Historically, there have been a number of vital institutions which have acted to generate, transmit and reproduce a version of anticapitalist thinking on a mass scale. Trade unions, along with socialist and social democratic parties like Labour in Britain, acted as a repository of working class ‘good sense’, reaching across generations and functioning as an imperfect but meaningful counterpoint to the mainstream political discourse, which has invariably been dominated by less radical ways of understanding the world.

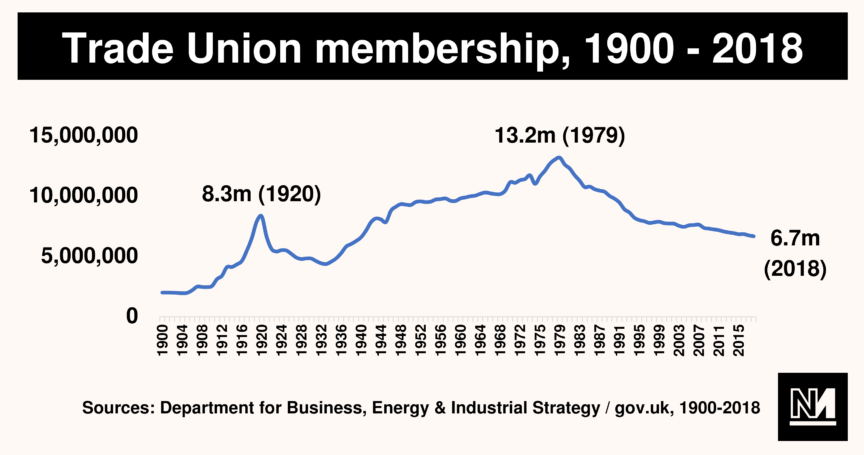

The decline of these institutions over the last four decades (or, arguably, longer) is crucial to understanding the electoral weakness of the Labour party today. Official figures show a decline in union membership from almost 50% of employees in 1979 to just 24% now. But even this substantial decrease disguises the true scale of the problem, since the majority of remaining trade unionists are in the public sector, leaving most of the workforce outside of the unions’ immediate reach.

The statistics are bleak. In 77% of all private sector workplaces, there is not a single union member present. Half of all employees have never been in a union, compared to just 20% in 1985. And what’s more, the movement is ageing: 38% of trade union members are over the age of 50, with just four percent younger than 24. An entire generation of the working class in Britain largely sees trade unions and the labour movement as relics of the past.

We have, then, a situation in which the material conditions of the young have the potential to lead them towards a radical critique of capitalism, but the traditional institutions that would have helped inform such a critique have been largely removed. In the absence of such important infrastructure, the ideas themselves can become rather free-floating – a pick-and-mix of whatever is available to help make sense of the world.

The internet further reinforces this unmooring of ideology; it’s possible to find any opinion imaginable from just a quick Google search. And, of course, the algorithms these websites use are designed to keep feeding you agreeable content, creating feedback loops and echo chambers that reinforce whatever opinion you started out with.

Brits have never really backed neoliberalism.

Meanwhile, the legacy media still frames politics around neoliberal supposed truths, from the promotion of entrepreneurship to an insistence that the market is the best way to organise society, echoing and reinforcing the messages propagated by successive governments over the last four decades. Consequently, the space for dissenting viewpoints is seriously constrained. Under these circumstances, what’s really impressive is not that younger Britons are on the left, but that more of them aren’t stridently rightwing.

That said, despite neoliberalism’s total dominance over government thinking, along with its squeezing out of basic social democratic arguments from mainstream discourse, the ideology has gained surprisingly little hold in the wider population.

British political beliefs have remained stubbornly (if weakly) collectivist throughout that entire 40-year stretch of neoliberal governments. The British Social Attitudes survey consistently finds that around a third of the population – even at the peak of Thatcherism – is always resolutely social democratic in their attitudes: always wanting more redistribution, always wanting more public spending. But with both Labour and the Tories committed to a version of neoliberalism from the mid-1990s onwards, this solid base of support was consistently denied real political representation.

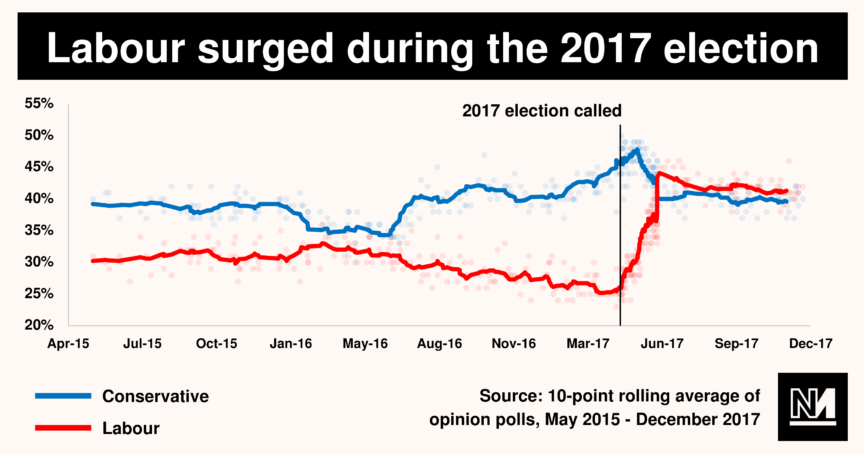

It wasn’t until Jeremy Corbyn became Labour leader in 2015 that the left was able to successfully draw on this buried support for basic socialist ideas. The surge in support for Labour during the 2017 election really shocked the establishment because the discourse it was drawing on had been so excluded from mainstream discussion. At its peak, Corbyn was also able to capture a more diffuse anti-elite sentiment, expressing a deep cynicism about the running of the country – a sentiment that the rightwing Vote Leave campaign also managed to successfully coopt.

But residual support for social democracy, and a great deal of cynicism, are not enough for the left to win back power. Cynicism, in particular, can cut in many different directions. The Johnson regime’s own combination of anti-austerity and “levelling up” rhetoric, combined with a brazen cynicism about the distribution of government funds – dishing out contracts to their friends, and targeting spending on Tory marginal seats – is one way that this kind of strategy could play out.

In other words, if a great chunk of Generation Left is currently looking leftward, it would be a big mistake to think that such an outlook is guaranteed. Compare, for example, the ideological positions of young people in France and Britain. While housing is less of a chronic problem in France, insecurity, low pay and a lack of future prospects certainly are. But despite British and French young people sharing a common material experience, the political conclusions being drawn by those in France are radically different, with Marie Le Pen’s far right National Rally party topping the polls. Material differences alone are therefore not enough to explain the divergent political outcomes.

Young people are more likely to change their minds.

Indeed, digging deeper into Generation Left’s attitudes and ideas, we start to see just how potentially fragile their support for socialist ideas really is. The IEA’s survey is an apt example of this. While, on one hand, there are clear majorities in support of anti-capitalist ideas (“capitalism heightens racism”: 70% agreement; “capitalism causes climate change”; 75% agreement), there are also similar majorities for completely opposite perspectives (“Racism has existed in all economic systems. There is no reason to believe that there would be any less racism under socialism”: 70% agreement; “capitalism can help deal with climate change”: 65% agreement). Majorities within this same group believe both that, “Capitalism encourages selfishness, greed, and materialism,” and that “The profit motive is good for society”.

It shouldn’t be all that surprising that people often hold contradictory ideas – and, of course, the wording of the questions play a part, leaving little room for nuance. The same clashes also exist on directly counterposing policy questions: there are, for example, majorities for raising taxes and majorities that argue taxes should not be raised for fear of irresponsible government spending. Similarly, there are majorities for rent controls and majorities for removing housing market restrictions.

All of this points to a substantial amount of fluidity in people’s ideas, with young people more likely to be less fixed in their views. The harsh reality is that young people’s attachment to any given set of socialist or even social democratic ideas and policies is rather weak.

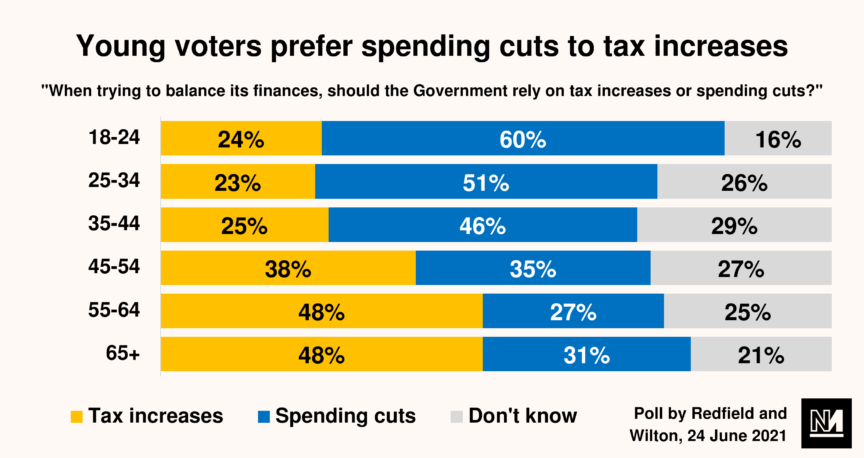

Case in point: a more recent poll by market researchers Redfield and Wilton Strategies, which asked how the government should “balance its finances”, found that 16-24-year-olds are overwhelmingly in favour of spending cuts over tax increases. While the framing of the question – centred on the need to “balance government finances” covid debts – is diabolical, it still reinforces the point that, when presented with a constrained choice, younger voters will not automatically opt for the more socialist solution. This is likely due to British people’s profound lack of faith in government, following ten years of brutal Tory austerity.

Alongside this clear support for entrepreneurial policies, polling also consistently finds that there is a real appetite among young people for starting their own businesses. In a recent survey, 82% of 16-24-year-olds said that they were “interested” in the idea; while the number of teenagers actually starting their own businesses has risen from 500 to 4,000 a year over the last decade.

Although it is not yet clear how and where this burgeoning entrepreneurial spirit will fit into the left’s basic economic programme, outright opposition to those wanting to start a business seems unwise if the left is serious about trying to build a broad coalition of support.

Young people want security.

In the wake of the June 2017 election result, rightwing thinktank The Legatum Institute found that 18-34-year-olds were notably more pro-business in their attitudes than their older counterparts. The researchers even noted that “Opposition to capitalism is often presented in the media as a preserve of millennials, but it is in fact those aged 35 and over who are most opposed to capitalism”.

Another priority for young people is homeownership, with 91% of under 35-year-olds “aspire” to own their own home; 70% of those, however, believe this is now an impossibility.

Historically, the left has failed to address this demand directly, preferring to focus on the expansion of council housing – which could very well be a route to homeownership, but tends not to be framed in this way. The Tories have been similarly bad at capitalizing on this strong pro-homeownership sentiment, notoriously failing to build even a single one of the 200,000 starter homes they promised in 2015.

Even so, it remains a risk that the Conservatives will devise a popular and radical housing policy in the future and begin to drag Generation Left to the right. Proposals floated by Tory-leaning thinktanks have included a partial ban on the overseas ownership of homes and the creation of a ‘Right to Buy’ for renters. And what’s more, prime minister Boris Johnson is clearly prepared to challenge at least some traditional Tory beliefs around the economy.

Young people’s desire to own a business or to own a home is completely understandable given how many of us are stuck in increasingly precarious situations; both involve holding wealth in some form and look like a guarantee of future security. It is more obvious to those who have never – in their adult lives – experienced a relatively generous government, have enjoyed significant rights at work, or have been in a trade union, to look for forms of security centred on ownership, than it is to look to classic leftwing solutions to insecurity, such as increased government spending, labour market regulation or expanded trade union membership. Generation Left clearly believes in some version of all three, but these beliefs sit alongside other priorities and visions of the future.

So, how does the left win back power?

The slipperiness of Generation Left’s beliefs means that the efforts of organisations like The World Transformed to ensure that people are armed with leftwing political discourse have been vitally important over the last few years. Small as they still are, the fact that these groups are helping to create a space where a distinctive leftist analysis can be developed, transmitted, and reproduced is absolutely critical in winning broader support for socialist ideas. The various strands of leftwing media also perform a similar function.

Of course, none of this is happening on a scale that would secure the kind of profound, widespread change that is needed; much has to be rebuilt in the wake of the ousting of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader. Indeed, the simple fact of having a leader who was willing to communicate a socialist political analysis, and had the support of over 500,000 members, did more to shape the wider political discourse than almost anything else the left has done in a decade. Corbyn’s absence undeniably means that the cause of socialism has weakened.

But this is the ultimate weakness in the left’s position – the one that underscores everything else. Notoriously, ‘socialism’ is a highly contested term. The form of socialism that has come to dominate British politics, at least since the second world war, has emphasised action by a strong central government, whose job it is to redistribute resources and create universal, often free services. The NHS is an outstanding achievement of this ideological model, but much of its legacy has been dismantled over the last few decades. Thatcher privatised nationalised industries, Tony Blair undermined universal provision through means-testing, and David Cameron and Theresa May’s austerity programmes profoundly weakened the provision of public services.

If all you’ve received from your government is spending cuts and increasingly precarious labour and housing situations, it’s hardly surprising that many people look to more individualised solutions. When cynicism about government is so widespread, it becomes critically important that the left is able to meet people’s real needs and demands. The opportunity is clearly there for the right to regroup and offer its own ‘solutions’ to Britain’s ongoing economic failure. And there is no reason to assume that genuine and positive solutions will win out over the fake.

So long as the left commits to a socialism that stresses historical democratic solutions instead of directly addressing the material conditions of Britain’s young people – and in terms they can easily understand – it will remain wide open to attack.

Ultimately, if it wants to keep Generation Left on its side, the left must focus on clearly and directly addressing young people’s need for material security. This means thinking creatively about meeting the specific demand for ownership in its different forms. Universal Basic Income is popular across the population, but even more so with the young. This is a perfect example of the kinds of policies the left needs to be pushing; it is a clear and simple demand, with immediate benefits.

And on housing, the left must be less squeamish about meeting the demand for ownership – whether through a tenants’ Right to Buy scheme, cheap, local authority mortgages, or countless other methods. It should also be championing community wealth building programmes like the Preston Model – which Labour might just be doing – not only stressing their importance in meeting social and environmental goals, but, crucially, how they can support small businesses and worker ownership too.

The political landscape has changed over the last decade. The left must recognise this and respond in kind. If not, it risks handing a generation to its political enemies.

James Meadway is an economist and Novara Media columnist.