Whoever Wins the Green Leadership Race Must Seize the Moment

Play their cards right, and we could see another Green surge.

by Matthew Butcher

13 August 2021

There’s rarely been a Green party leadership race quite like the one which begins on Tuesday. With Jonathan Bartley stepping down and Sian Berry deciding not to stand for re-election, this will be the first election since 2012 with no incumbent and no clear favourite.

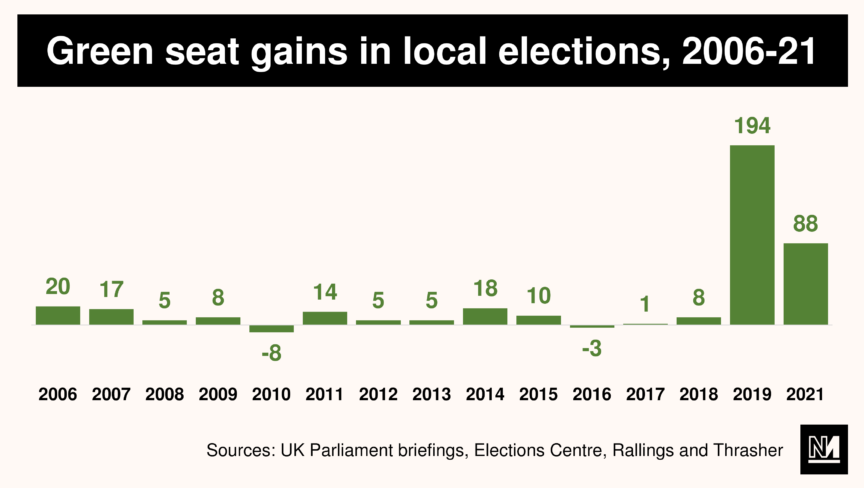

It’s not just likely to be the most competitive leadership election ever for the Greens, but it takes place at a time when the party has the opportunity to take some serious steps forward. The leader will inherit a party with a record number of councillors (477 across 141 councils) – a testament to a targeting strategy spearheaded by the party’s secret weapon, Chris Williams – and thereby a ready-made army of canvassers. But electoral success hasn’t just been about this clever targeting strategy – it’s also because the public is increasingly voting Green. As Ell Folan observes, the party is flying higher in the polls than it has at any time since 2015. The Greens tend to do better when other social democratic parties are perceived to move to the centre – and Labour under Keir Starmer is well and truly feeding that perception, with appeals to imagined ‘red wall’ voters taking precedence over building on the base Jeremy Corbyn so successfully mobilised in 2017.

But that’s not all. The Greens also do better when the environment is a top issue for voters – which it currently is. We are now firmly in the grip of the climate crisis, and it’s hitting communities here in Britain as well as across the world. From water pouring into our homes to our elderly relatives dying from heat waves, climate breakdown is now a part of what we’re seeing and hearing every day in Britain – and it’s increasingly an issue that influences how we vote.

The environment will continue to be a major issue as long as the government keeps talking about it, which they are being forced to by climate activists and campaigners. And the more the government makes climate-related policy announcements, the more the Greens have space to demand better than what’s on offer. As a study for Democratic Audit shows, “major party pro-environmental statements tend to benefit the Greens”.

So the scene is set for success for the Greens. But what might a new leader do to grasp the moment?

The first thing is to jump at the opportunity presented by Starmer’s leadership of the Labour party. The votes to be gained from Labour’s political shift are from those who care about the climate crisis but also want a party that offers economic radicalism and unequivocal support for marginalised groups. This means the Greens should keep talking about the environment, of course, but also push popular policies like a wealth tax, and continue to publicly back the rights of trans people – like the majority of the British public and young people in particular.

If Starmer is going to keep pitching Labour as the party of policing and patriotism, the Greens should be talking about drug law reform and popular democracy. There is also a glaring space in British politics at the moment where big ideas should be.

Despite huge wins amongst 18-24s in 2017 and 2019, Labour’s support amongst young people has fallen back – with the Greens surging.

📊 by @LeftieStats pic.twitter.com/fC9UMRp8Nq

— Novara Media (@novaramedia) June 17, 2021

The important point here is that the new Green leadership must ignore those who at every leadership election say the party must talk more about its core issue: the environment. It did this at every general election until 2005, and singularly failed to win any seats and, frankly, not many votes at all. If the environment is a salient issue, the Greens do well – but they’ll win more votes when they show they have a serious policy platform. Recent research commissioned by the party points to the fact that the public knows, understands and rates the Greens’ environment policy, but as one insider told me, “they need to hear from us on where we stand on social justice”.

If the public need to hear more from the Greens on non-environment issues, then the mainstream media will be key in doing so. Even an inarticulate and unimpressive leader of the party will likely see a good few years ahead of them, but being able to land media appearances with impact is what the leadership can offer. Caroline Lucas, still by far the most recognised person in the party, has shown how possible it is for Greens to perform in the media. And Natalie Bennett’s performances of 2015 – blamed all too often on her as a person and not on the lack of any proper party support – showed how the party’s credibility can fall fast.

And if the Greens are going to seek more representation in the media, then they must quickly address the serious and long-standing lack of diversity in its top team and across its elected councillors. This is both a matter of principle and strategy, as the party can’t seek to represent communities who are so sorely missing from its mostly white, mostly middle-class upper echelons.

The big electoral challenge for the next leadership will be to do what’s never been done: win a second parliamentary seat. This is a tall order. In 2019, the Greens lost their number one target seat – Bristol West – to Labour by a 37-point margin, albeit with a much improved vote share. But if the flight of young, left voters from Labour is to materialise anywhere for the Greens, it will be there. Gaining almost 50% of the vote in the constituency in the last council elections will give them hope, as will them being the joint biggest party on the council.

💚 We’ve taken Bristol City Council into No Overall Control after a whopping 13 GAINS!

✊ We’re now the joint biggest party on the council.

📈 Our vote share in Bristol West was a whopping 48%!

▶️ https://t.co/N7IGRtbLK6 pic.twitter.com/RKz1lZKDTl

— The Green Party (@TheGreenParty) May 9, 2021

There is a model for parliamentary success for the Greens, and you don’t have to look far to find it. The Scottish Greens, led by charismatic leaders, recently won a record number of seats on a genuinely progressive manifesto, and after a showdown against anti-trans voices in the party. Of course, in Scotland the Greens have the gift of a fair electoral system – but the party nonetheless performs well in a crowded field (alongside both the SNP and Labour) and is increasingly powerful.

Perhaps what matters most about this election for the new Green leadership is turnout. Only 16% of members voted last time – such a feeble percentage that it only reinforced the idea that leadership elections don’t really matter anyway. This time there’s a likely showdown between a number of serious candidates. Amelia Womack and Tamsin Omond have confirmed they are running on a joint ticket, and Cleo Lake has said she is considering it, while Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay are tipped to be in contention for the role. This won’t just be good for the party, but more importantly in my view, good for the wider left. A thriving Green party pushing to the left of Labour matters. It should do a reverse-Ukip, and drag the debate towards discussion of the systemic change we so desperately need. Labour will listen when the Greens threaten electorally, and additional Greens in council chambers and parliaments tend to bring focus to issues that are otherwise ignored.

Whoever wins the Green party leadership race has a unique opportunity ahead of them. The candidates’ first task is to seriously set out their stalls, making clear how they’ll do what the Greens do best: be a voice for social movements within the electoral system.

Matthew Butcher was formerly a press officer for Green MP Caroline Lucas. He now works for the non-party aligned New Economy Organisers Network.