David Graeber Was Right: A Debt Free World Is Possible

Mass debt cancellation isn't a myth; we're already doing it.

by Andrew Ross

30 August 2021

At the beginning of this summer, Juneteenth was finally designated a US federal holiday to commemorate the liberation of enslaved African Americans. It had long been celebrated in Black communities as Jubilee Day. When Frederick Douglas spoke of emancipation as the “trump of jubilee”, he was invoking the custom referred to in the Book of Leviticus; once the jubilee trumpet is blown (every 50 years), slaves and prisoners are to be freed, debts are to be forgiven and land is to be returned to its original owners.

Debt: The First 5,000 Years, David Graeber’s paradigm-shattering 2011 book, alerted a new generation to this ancient tradition. When a jubilee was observed in near eastern societies, upon the inauguration of a new ruler, the mass act of forgiveness was often presented as an expression of royal magnanimity. But, as Graeber pointed out, it was really a way for high elites to wrest power back from the creditor class, and to free the populace from working off their debts so that they could work for the glory of the state.

A people’s jubilee.

Shortly after his book’s publication, Occupy Wall Street declared war against the banks that had enjoyed a jubilee of their own when they were bailed out. Graeber was on hand to supply a rich political and historical framework for activists to issue their counter-call for a people’s jubilee.

Previous jubilee campaigns had been aimed at eliminating sovereign debts. In the 1980s, the Jubilee South movement sprang up to pressure rich northern countries and banks to write off the external debts of Global South nations caught in the ‘debt trap’. In recognition of the Great Jubilee – the celebration of the year 2000 in the Catholic church – the movement eventually succeeded in abolishing as much as $130bn of debt.

What was different about the jubilee movement that Graeber helped launch through Occupy in 2011, and in which I have played a role, was that it was aimed at erasing personal, or household, debts. Now, debt relief was framed as an act of justice (abolition), not one of charity (forgiveness), and it was rooted in an anarchist moral economy best summed up in a reversal of payback mentality; we owe the banks nothing, we owe each other everything.

Building a movement.

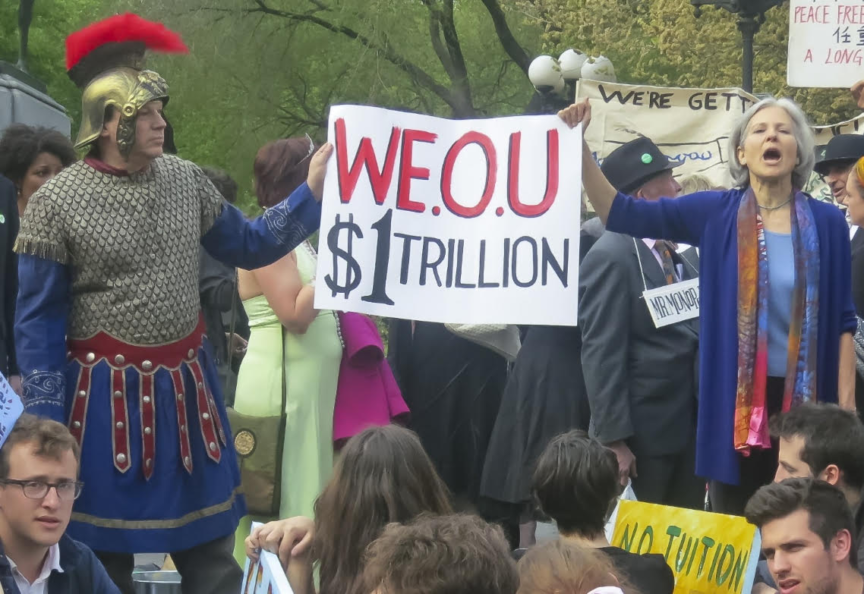

Our first initiative was the Occupy Student Debt Campaign, organised to persuade one million student debtors to default and put pressure on banks and federal lenders. For all sorts of reasons, we fell far short of the goal, but many of the principles and rituals of the debt resistance movement were forged in the course of that campaign. Strike Debt, the successor organisation, formed in the summer of 2012, looked beyond student debt to medical and housing debt, and grew chapters all across the US.

Graeber had a strong hand in Strike Debt’s two best-known achievements. The first was the collectively written Debt Resistors Operations Manual, which provided valuable information, in plain English, about how to negotiate your way out from under a debt burden. It circulated widely, and is still being downloaded and used today.

The second was a mutual aid initiative called the Rolling Jubilee, which crowdsourced funds from small donations to buy up debt cheaply on the secondary market and eliminate it. Over the course of a year and a half, we raised about $750,000 and bought up $32m of debt. Sure, it was a drop in the ocean, but it was also a highly symbolic act for its fans who cheered on the widely-publicised spectacle of debts being wiped out through a popular hack.

In 2012, we bought over $32 MILLION worth of debt for just PENNIES on the dollar. But instead of collecting it––we abolished it! This is how debt cancellation became a big thing!

Here’s why debt is so cheap & how we pulled off such a big stunt that we called “Rolling Jubilee.”

— The Debt Collective (@StrikeDebt) November 11, 2020

For us, the Rolling Jubilee was a way to expose the workings of the secondary market, and let people know that the collectors pay only pennies on the dollar for the debts they try to extract in full from us. It was also what we called a proof of concept – evidence that collective action can produce results in a financial domain long controlled by creditors. That principle lay at the core of Strike Debt’s successor, the Debt Collective, a more ambitious effort, launched in 2014, to form the first-ever debtors union. Organising around debt is not easy, but we see it as necessary and inevitable in a world where capitalism has come to favour predatory lending over productive investments.

Once the Debt Collective had acquired members prepared to organise and strike, the fruits of that collective action began to appear. Channelling that energy through legal mechanisms that we helped to devise, we succeeded in winning more than $1.5bn of debt relief for students from for-profit colleges. The larger goal now is full cancellation of the $1.7tn student debt burden. The Debt Collective recently provided the legal argument showing that the president has the executive authority to discharge these debts, especially the federal loans.

NEW: President Biden can cancel all federal student loan debt with a simple executive order. So, we wrote the entire executive order for him. All he has to do is sign this piece of paper.

>https://t.co/GezjStOQS8 pic.twitter.com/CtWZXQj6Z2— The Debt Collective (@StrikeDebt) June 14, 2021

To that end, earlier this year we launched the Biden Jubilee 100 debt strike to put pressure on the White House. At the time of writing, Biden, a long-time friend of the finance industry, is resisting the entreaties of senior Democrats like Chuck Schumer and Elizabeth Warren to do the deed. But even if only a portion of the burden is lifted, it will still be the largest jubilee since emancipation abolished chattel property.

Debtors’ unions are the future.

It’s been ten years since Graeber first promoted the jubilee concept in Occupy circles. Over the course of that decade, it has travelled from utterly left-field margins to the very forefront of debate among policymakers and the public. Some commentators have taken the pragmatic view and argued that large-scale debt relief is just the kind of economic stimulus that’s needed as the pandemic recession rumbles on. We see it on a much bigger canvas. Resistance to illegitimate debts – racked up for access to social goods like education and healthcare – is shaping up to be one of the frontline conflicts of the 21st century.

Just as the struggle over wages was (and still is) key to an industrialising economy, hard bargaining with the creditor class over debts is a requisite response to the financialisation of today’s economy, where the lion’s share of profits is extracted from people’s need to borrow to survive. We live increasingly in a creditocracy, a kind of advanced capitalist society that requires people to take out loans to access their basic needs, and where the accumulated debt can never be entirely paid off. In a creditocracy, the profit model is one of lifelong extraction in the form of debt service.

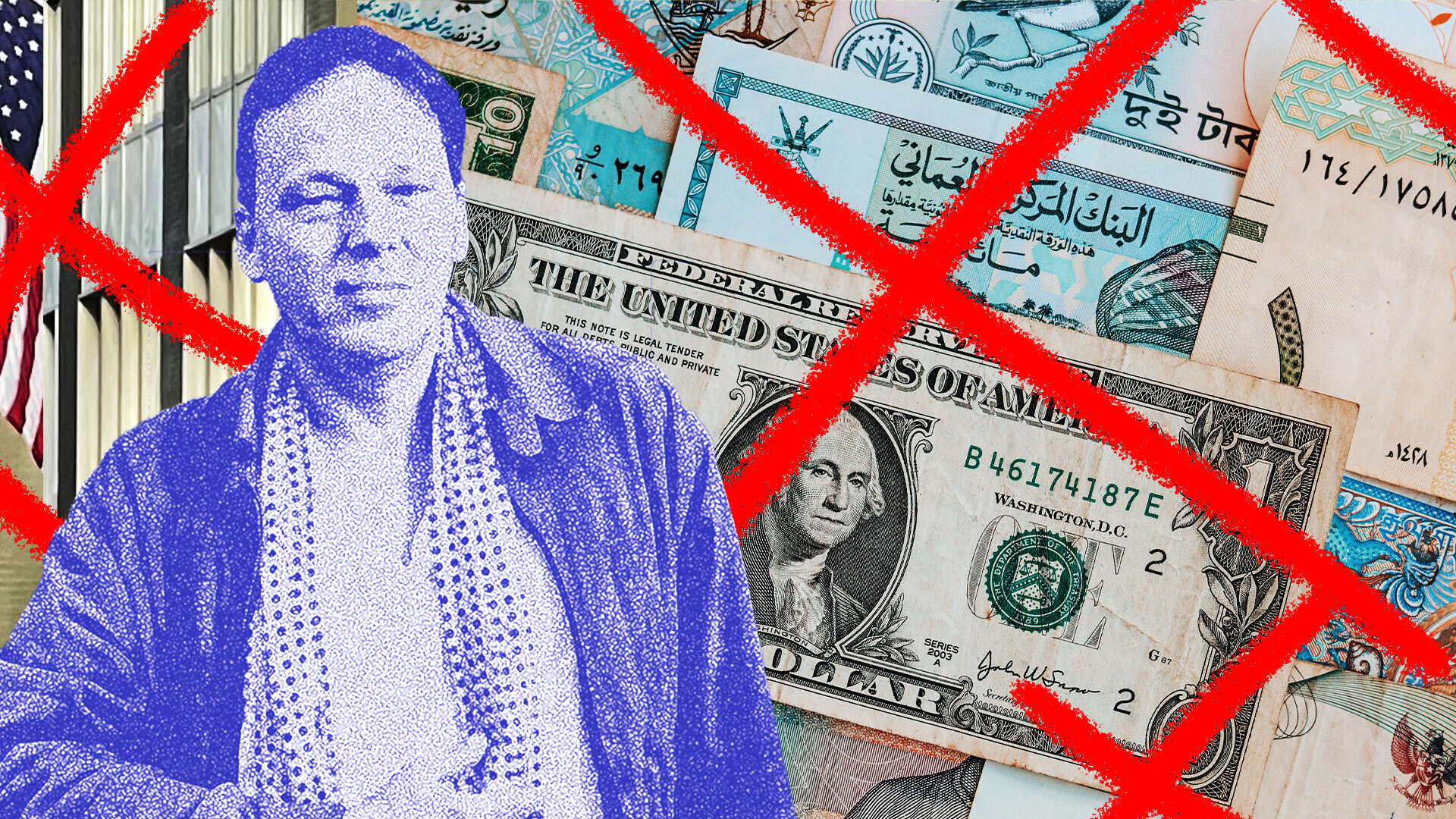

Successful resistance can only come from collective action. After all, the door is always open for individuals to renegotiate with their creditors. Even sovereign nations can petition the Paris Club – a group of officials from wealthy northern creditor countries whose role is to find solutions to the payment difficulties experienced by debtor countries – but they are not permitted to join together in requesting debt relief. In response, Thomas Sankara, the revolutionary then-president of Burkina Faso, proposed in 1986 a counter-bloc of debtors called the Addis Ababa Club, and was assassinated for the audacity of his vision.

Thomas Sankara: “Debt is a cleverly-managed reconquest of Africa.” pic.twitter.com/ciWRHCUt7Z

— Jacobin (@jacobin) December 21, 2018

Bankers themselves are all too aware of this threat to their power. As J. Paul Getty put it: “If you owe the bank $100 that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100m, that’s the bank’s problem.” Mass mobilisation, through debtors’ unions, is vital in shifting this balance of power and bringing about much bigger settlements. Not only is this a form of redistributive politics, but it also possesses utopian grandeur when it comes in the form of a jubilee.

Under this recalibration of power, debt will not disappear, but predatory lending will. People will still need credit, for all kinds of reasons. Financial institutions will need to be reconstructed to serve public and communal needs, and so they will only offer socially productive credit. This is not a pie in the sky. Our experience over the last ten years shows that such a world is possible. But, as with every other struggle in history, it will only come about through cooperative energy and action. Debtors of the world unite! You have nothing to lose, not even your credit scores.

Andrew Ross is an NYU professor and social activist. He is the author of Creditocracy and the Case for Debt Refusal, among other books.

This is the first instalment in our series exploring the life and ideas of David Graeber on the first anniversary of his death.