Workplace Struggles and Plans for Government Must Go Hand in Hand

Taking unions "back to the workplace" is a good thing - so long as national political demands don’t get left behind.

by James Meadway

7 September 2021

Sharon Graham’s decisive victory in the Unite leadership election last month – defeating both the favourite, current assistant general secretary Steve Turner, and the darling of the union right, Gerard Coyne – has understandably provoked arguments amongst the left. While some have welcomed Graham’s distinctive workplace-first, ‘syndicalist’ approach to union politics, others have been much more critical.

While the specifics of the candidates’ campaigns and the union’s internal politics have already been well-covered, it’s important to put this election in its wider context. Most notably, like the 2019 general election defeat, Graham’s victory in the Unite election marks the end of a decade or so of relative success for a particular kind of left strategy. Coyne’s defeat is a victory for the left, of course – and whatever happens next, it’s clear the labour movement isn’t turning to the right. But this wasn’t a victory for the left that has dominated Unite almost since its formation.

Since Len McCluskey was first elected general secretary in 2011, Unite has followed a very clear and overtly political strategy: that crucial to the success of the union movement was winning a Labour government that would support it. Fundamental to this were attempts to shape the Labour party so it supported union and left demands more generally, which meant Unite using its influence as the largest affiliated trade union to support favourable parliamentary candidates, push for pro-union and socialist policies inside the party, and support leaders that were aligned with them.

Of the many strategies pursued by different branches of the British left since its heyday in the 1970s, this has been the most successful by some distance. The left faction inside the parliamentary Labour party was, under Jeremy Corbyn, the biggest it had been for years. Labour’s default setting across a range of domestic economic issues is still solidly to the left of Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband. And most notably, neither the leadership elections of Miliband nor Corbyn (twice!) would have been possible without Unite’s support.

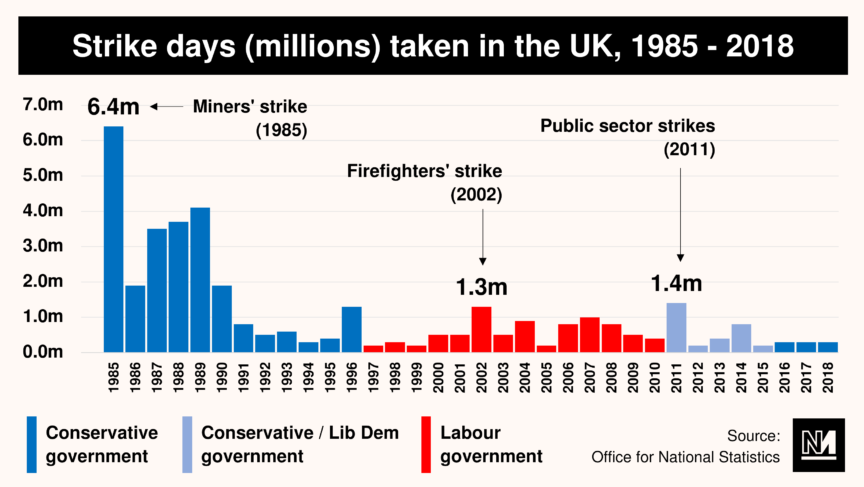

But there was always a significant contradiction in this strategy, as can be seen in the graph below showing the number of strike days taken in the UK from 1985, the last period of the miners’ strike, to 2019. Once the 1990s hit – bringing recession, further anti-trade union legislation, and, under pressure of defeat, a further shift to the right inside both the Labour party and the trade union movement – strike action fell off a cliff, never to recover. In this respect, we are very much still living in the long 1990s.

A ‘political’ strategy for a union, like that which Unite pursued under McCluskey, can be seen as a reaction to this: that if union organisation is weak in workplaces, it can still assert itself in the political sphere. But this strategy was then itself bounded by the weakness of unions in their core function of providing workplace representation and bargaining power for workers. There were limits to how far the politics could run ahead of industrial reality. Once Unite’s political strategy ran into the brick wall of the 2019 general election defeat, provoking rows and splits inside the dominant Unite left faction, some sort of correction back to industrial reality was always likely. Coyne’s gamble was that this would snap back to the right. Graham’s bet was the exact opposite – and it paid off.

At the same time, however, there is always a risk in seeking to depoliticise union issues: at some point, your demands in the workplace start to run into some hard facts presented by either the operation of the law or government intervention. The Labour party itself was set up precisely in recognition that neither of the two favours worker organisation. Right now, under the conditions of Covid-19, that risk – that workplace struggles end up dragging in the government – looks more immediately pressing than it has done for many years.

Let’s take a moment to assess the current situation more closely. Covid-19 has pulled the government further into economic questions on a number of fronts. The decision to implement furlough, for example, was taken under pressure from and in consultation with the union movement, with Unite playing a key role. Despite government efforts to subcontract the distribution of furlough payments to employers, decisions about winding down or continuing support, or changing the kind of support given, are necessarily political. Union organising itself, however, runs rapidly into a legal minefield, with extraordinary obstacles barring union activity – obstacles that Unite had, notably, become good at working its way round, but obstacles nonetheless. Decisions about procurement for PPE are political. The decision to nationalise a ‘strategic’ steelmaker is not only political, but turns the government into an employer. And all the signs point to continuing government intervention in the economy as neoliberalism recedes.

This contains a danger on the government’s side. Whereas neoliberalism (and particularly classical liberalism) would make a great show of government being a neutral arbiter in any labour dispute, this pretence is harder to maintain if the government is literally the employer, or directly subsidising or paying for some economic activity. It is politically easier for governments to detach themselves from employers’ actions; it is economically becoming harder for them to avoid doing so.

And if, as suggested, the conditions of employment under Covid-19 continue to produce tight labour markets – with labour shortages driving up wages and increasing workers’ potential bargaining power – the conditions for an upsurge in workplace organisation are in place. There is some evidence this is already happening: union membership continues to rise from an all-time low, and strikes may be picking up. But these conditions will hold for as long as Covid-19 holds, and, notably, restrictions are necessary. Whilst it’s obvious Covid-19 isn’t going to go away, the argument over how and when work can be performed safely is, by itself, already a route to politicising any workplace dispute and more liable to involve the government in some form.

Where does this leave the post-Corbyn left? I’d make three observations. First, if the government is intervening economically in a big way and these interventions work to the benefit of employers, there should be greater caution about government intervention as such. We must become better at defending basic civil liberties and so-called ‘liberal’ values, and look for wide political alliances in doing so.

Second, independence should be a watchword: independence of workplace organisation on one side, with unions able to organise freely without employer or government interference (implying, incidentally, that their rights to do so need to be significantly expanded – such as in dropping the daft postal ballot requirements for strikes); and independence of the left itself. We need self-funded institutions, as far as is possible, notably in sustaining a viable left media ecosystem.

Third, hopes of national political leadership can’t get left behind. Ultimately, the left can and should be aspiring to not just gripe about how rubbish everything is, but to run the country. To do this we have to show, continually, that we not only have better solutions, but that we are serious about wanting to implement them. In Britain today, that means having a relationship to the Labour party, and making calls as to what its leadership should be doing whether we think they will or not. What Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams called ‘folk politics’ is always a lure: that if we just concentrate on local activities, or workplace organisation, the big political questions will resolve themselves. In practice, this means ceding ground to the right. It’s only when political issues are expressed in the form of national political demands, and ultimately in a programme for government, that they move from mere complaints towards attempts to seriously reshape the world. It would be a historic strategic error to now retreat from that aspiration in favour of workplace organisation alone.

James Meadway is an economist and Novara Media columnist.