Yes, China’s Debt Bubble Might Burst – But the Government Has Far Bigger Problems

Turns out spectacular growth comes at a spectacular price.

by James Meadway

11 October 2021

Evergrande, the world’s most heavily indebted property developer, is teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. Having missed two payments to its creditors last week, trading in Evergrande’s shares has been suspended, as Chinese authorities move to try and contain any potential economic damage caused by its financial woes. Meanwhile, in a sign of wider trouble for the $52tr Chinese property market, luxury developer Fantasia Holdings Group Co. defaulted on a $205m loan earlier in the week.

Many have drawn parallels between China’s current financial woes and the 2008 financial crisis. When Lehman Bros, then the third-largest investment bank in the US, filed for bankruptcy on 15 September 2008, it set off a wave of further financial failures, igniting a global economic crisis and a subsequent recession.

Some economists now fear that the potential bankruptcy of the Shenzhen-headquartered Evergrande could trigger a similar wave of defaults among its creditors, in the event that the debt bubble explodes, pulling international lenders down with it.

The cash crunch faced by property developer China Evergrande Group in recent weeks has drawn comparison to the 2008 financial crisis https://t.co/kY9Ap7S3ta

— Bloomberg Opinion (@bopinion) October 8, 2021

While China’s leadership has previously overcome financial crises – the stock market bubbles of 2013 and 2015, for example – the next few weeks will be a critical test of the government, led by president Xi Jinping’s, ability to contain the fallout of Evergrande’s failure.

That said, Evergrande’s impending collapse is part of a far bigger problem, after a decade in which borrowing was allowed to mushroom, fuelling China’s growth but at the cost of astronomical debts piling up across the economy. Extricating itself from this model is thus now a top priority for the Communist party.

The high price of exponential growth.

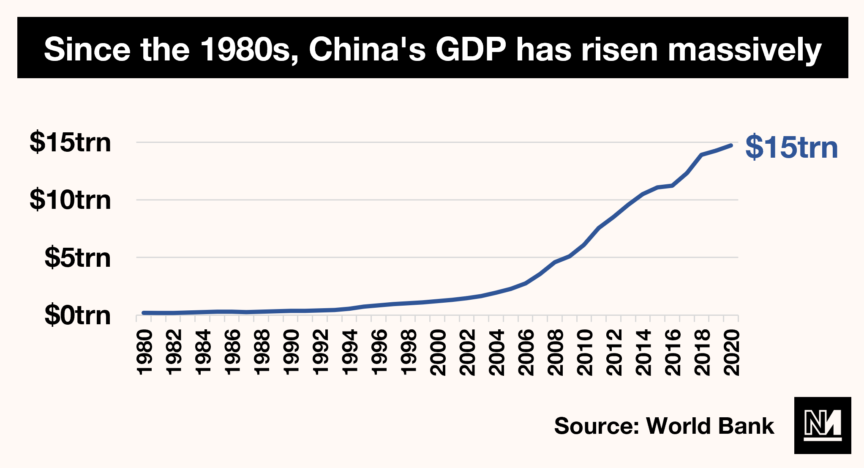

China’s economic growth has been reliably spectacular for the last 40 years, with the government turning what was a huge but poor country into the world’s second-largest economy, lifting millions of people out of the worst forms of poverty, and sparking panic amongst the US elite, who fear a challenge to their own global dominance.

This growth, however, has come, at an equally spectacular price. With thousands of factories opened, mega-cities constructed, and coal power plants put into operation, the country’s ecological footprint has grown enormously. Pollution in China’s cities has sparked environmental protests, whilst its leadership has started making big promises to reduce the economy’s environmental damage.

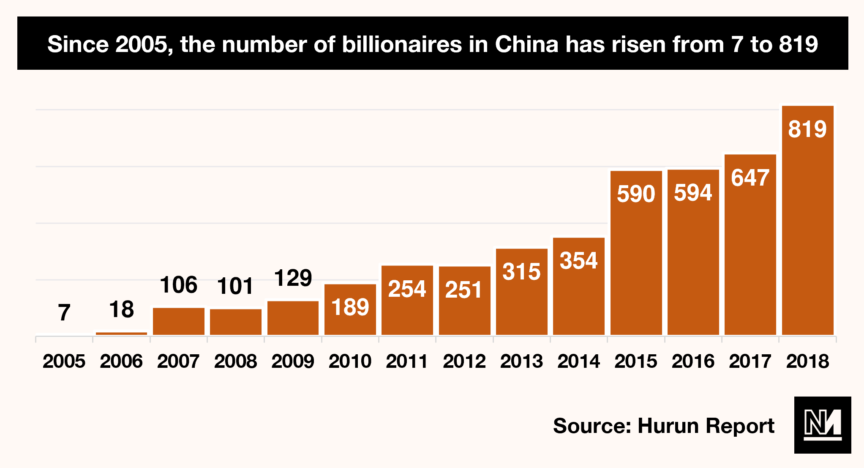

Meanwhile, inequality in China has skyrocketed. Although some 400m people now earn more than the World Bank’s one-dollar-a-day definition of absolute poverty, millions still earn very low wages, especially in rural China. Despite this, the country has still managed to create record numbers of billionaires. While the country’s economic growth has been fast enough to create some prosperity on a wide scale, it has ultimately benefitted a very elite few far more than it has ordinary Chinese people.

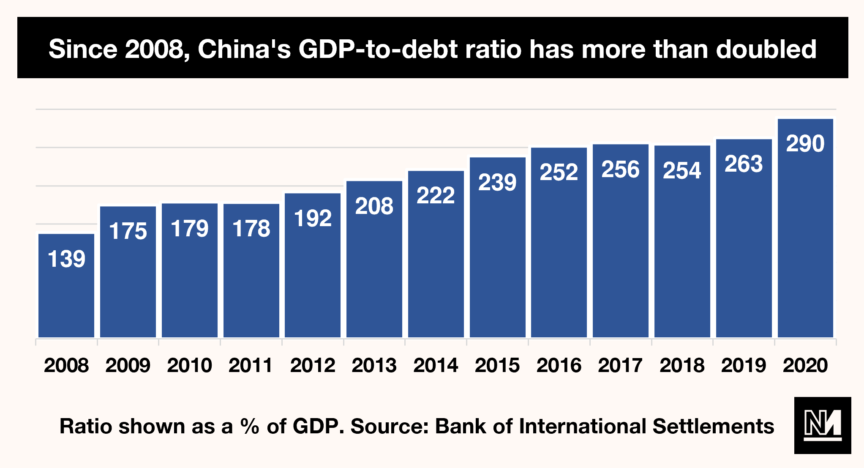

Less visible, since the 2008 crash, has been the growth of a debt bubble within China’s economy that is now larger than those of notoriously debt-heavy countries, like the US or the UK prior to their own bubbles bursting. China’s total debt to GDP ratio, which measures the size of the debt of everyone in the country relative to the size of its economy, now stands at 270%.

That said, China’s bubble has marked differences from the US and UK’s in 2008. China’s household debt is now worth 52% of household income, which is significantly below the levels reached by the UK (150%!) or the US before the crash – but a big jump on previous years. Where US households held most of the country’s debt in 2008, in China’s case, this debt is largely held by Chinese local government and other semi-public bodies as a direct result of the efforts made by China’s leadership to insulate the economy from the global recession following the financial crisis.

A short-term fix.

As the global recession unfolded over 2009 and beyond, China’s government moved rapidly to support its domestic economy, launching an impressive Keynesian programme of public spending to support jobs and – it should be clear – to exploit the relative weakness of western economies.

In the short term, this worked incredibly well: China powered through the recession, maintaining a high rate of economic growth, at over nine percent a year – which, incidentally helped to support the global economy, by providing a growing market for countries across the world to sell their goods and services into.

However, this rescue came at a price. First, there was the classic capitalist problem of ‘overproduction‘. While government support helped to sustain domestic demand for essential industries like steel – production of the metal increased 12-fold in 25 years up to 2016 – steelmakers chasing profits meant they produced more than China’s domestic market could buy. This, in turn, provoked the government-approved ‘dumping’ of cheap steel on global markets, undermining producers across the world, and leading directly to the closure of a steel plant in Redcar in England.

The closure of SSI Redcar steelworks in 2015 led to 7000 job losses and devastated local communities. Our post-Brexit trade defence regime must stop this ever happening again: https://t.co/wxKE2MWkAU pic.twitter.com/olrUqtHjt1

— Trades Union Congress (@The_TUC) May 22, 2018

Secondly – and perhaps even more importantly – there was the problem of the debt issued to provide money for additional spending, notably on infrastructure. Alongside this increase in government spending, restrictions on private-sector borrowing were also loosened.

Thanks to China’s system of local property taxation, in which rising property values could be captured through local taxes, local and regional authorities were heavily incentivised to direct this flood of capital into property development – a move which helped steer lending from the wider financial system into local development, with local authorities hoping to capture future property taxes from new buildings.

Because of all this, China’s property boom has been – even by its own superlative standards – extraordinary. Accounting today for an estimated 25% of its economy, by 2011, the Chinese construction sector was building the equivalent of a city the size of Rome every two weeks.

And what’s more, The rapid pace of economic growth itself encouraged greater borrowing; if part of an economy is booming, it creates a big incentive for other investors to try and pile into that sector, or else risk losing out on potential profits. So for a time, the expansion of a bubble is self-sustaining – in China’s case, because property prices are going up so much, more investment is attracted into the sector, helping further fuel its expansion and a further spike in prices.

But the problem is, by taking on more debt, developers also now have to pay a lot more in interest. This is exactly what’s happening in China, with property developers now having to repay $54bn of loans this year – a massive increase, on last year’s $25bn repayments. Thus, heavily indebted property companies are the major weakness in China’s economic system today, with Evergrande at the top of this wobbling pile of property-related debt.

A property Ponzi scheme.

Evergrande’s on-balance sheet $300bn debt is equivalent to about two percent of China’s entire national economy. Meanwhile, a further one percent is estimated to be tucked off-balance sheet in the country’s ‘shadow banking system’ – its vast, $13tr system of unofficial and unregulated lending.

Even so, Evergrande itself only accounts for four percent of the total Chinese property market, which is heavily fragmented into many thousands of developers. This splintered market further boosts the bubble, since – given the fierce competition between them – each developer has a major incentive to try and get ahead of its rivals by building more, and taking on more and more debt to do so – or risk being pushed out of the market.

Evergrande is quite large in China, holding total assets of over USD 367bn, or over 2.3% of China’s 2020 GDP. However it is far smaller than Lehman in scale, which held USD680bn of assets (amounting to 4.6% of US 2008 GDP) when it failed.

Source: DBS— Prashant Mahesh (@PrashantmET) October 7, 2021

Typically, a property developer will sell its unfinished properties as quickly as possible, and then use the cash from the sale to borrow more money and build even more properties. This is the business model – or, if you like, the Ponzi scheme – that Evergrande has relied on for the last decade.

Bigger picture, bigger problems.

But while the risk of Evergrande’s failure is very real, the greater concern is that this failure would drag other heavily indebted finance and property companies down behind it – with the developer’s failure to make payments on its loans in turn pushing its lenders into crisis as their expected income disappeared.

This is the worst-case scenario for China’s financial regulators, with the possible explosion of the debt bubble threatening to derail the plans of China’s current leadership. Xi’s accession to ‘paramount leader’ in 2012 was initially greeted by many in the west as a return to ‘liberalisation’ in China – meaning both more democratic freedoms, but also more free market reform.

However, the stock market crash of summer 2013, which threatened to impoverish smaller savers and undermine domestic political stability, seriously spooked the Communist party. In response, the government acted quickly to prop up the market and bail out some savers. Since then, it has made a pronounced turn against more free market-led approaches.

Under Xi’s leadership, the government has promoted the expansion of high-technology manufacturing and domestic demand (sloganised as “dual circulation”), and has claimed to be reigning in China’s inequality (and corruption) in the interests of boosting middle-class living standards (sloganised as “common prosperity“).

In a recent essay, Xi railed against the ‘inflated growth’ of the property bubble, arguing that bubbles, and the instability they cause when they burst, are a direct challenge to the party’s long-term economic plans, and to the country’s overall political stability. With that in mind, the government’s aim with Evergrande is to, as far as possible, contain the damage of its collapse – much as, after watching Lehman Bros fail in 2008, governments across the west then rushed to prop up and bail out failing banks.

In the longer term, China’s property market was always likely to subside. It was the growth of China’s working class, expanding rapidly as it was integrated deeper into the global economy, that in turn pushed demand for exceptionally rapid urbanisation.

However, that underlying demand for urban space is now easing off, as China’s population ages, and population growth slows. As a result, the pattern of Chinese development over the last two decades – of mass urban growth driven by mass production for export and the employment of cheap labour – is reaching its limit.

Abandoning the growth model.

It is in recognition of these limits that the government is seeking to build up the domestic market, supporting a mass-consumption middle class and overseeing comparatively rapid wage rises. China’s most recent Five Year Plan, covering 2021-2025, talks of supporting a “new development stage” of “quality development” in its place.

But building up this new, wealthier domestic market means extricating itself from the growth model it has upheld for the last 20 years. Over-indebted speculators like Evergrande need to be taken out of action, but, like defusing a bomb, this has to be done with exceptional care.

Allowing Evergrande to fail risks a Lehman-style conflagration – Lehman itself failed when the US government refused to offer the bank assistance. But propping up developers merely pushes the problem into the future and creates a ‘moral hazard’ – or, what is known in economics as the ‘spoiled brat’ problem; when failing to punish someone for doing something stupid and antisocial simply encourages them (and others) to be even more antisocial and stupid because they know they can get away with this.

A good example of this is the US’ comparatively successful $3.65bn bailout of the failed hedge fund Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) in 1998, after it bet heavily on the Russian rouble, fed the false sense of security amongst financiers that sufficiently large and stupid bets would always be bailed out, thereby helping to produce high-risk idiocies like the collateralised subprime mortgages that blew up a decade later in the 2008 crash.

A risky game.

As Michael Pettis argues, for the last three decades, China’s financiers have acted in the belief that, at some point, the government will always bail them out, encouraging them to take bigger and bigger risks – particularly in making wild bets on property markets. When growth was rapid and apparently unlimited, this didn’t matter too much – and at various points in the last decade, the government intervened to support markets.

But, of course, even now the Chinese government doesn’t mind some of the risky investments failing, since those failures serve to discipline the market – which, in turn, fits in with its broader mission to turn away from a model of risky, debt-dependent growth. That said, it is crucial that it stop those financial failures from spreading, Lehman-style, into the wider financial system and then the wider economy, outside of property and finance.

So far, the government is attempting to walk this tightrope – allowing speculative investments to fail, and containing the damage when they do. In practice, this has meant it moving in to support Chinese small savers, and those who bought homes from Evergrande. 1.6m home buyers are estimated to have placed deposits with Evergrande for homes that are yet to be built, and Chinese regulators have made clear they consider them a priority.

Maggie Hu said the sight of half-built homes has likely scared off many investors and home buyers — and reduced their confidence not only in Evergrande but other Chinese property developers. https://t.co/tbxTMupagB pic.twitter.com/tuQxs4cA01

— Insider Asia (@InsiderAsia) October 8, 2021

But this also means letting Evergrande’s creditors see their loans to the company fail if necessary. As a result, creditors in the rest of the world, who loaned Evergrande money in the expectation of high returns, are particularly exposed. Evergrande’s largest foreign creditors include UK investment fund Ashmore, US asset managers Blackrock, and international banks UBS and HSBC.

Few, in China or outside, will shed tears for their losses – who would, given their far from exemplary track records? – and larger institutions will be able to absorb the losses. But there is still some risk of the crisis spreading if those failed Chinese bonds are held by smaller and heavily indebted institutions outside of China.

Fixing a broken system.

While it’s unlikely – though not impossible – that we’ll see a second Lehman-type crisis from Evergrande’s failure, with bad debts stacked up across the Chinese economy, and the impacts of both the pandemic and the energy supply crunch – from semiconductor shortages to spikes in gas prices – continuing to be felt, smaller financial failures are highly likely.

Chinese property firms may face a wave of defaults next year if China Evergrande’s deepening debt crisis shuts access to a key source of funding https://t.co/M1hYd19tpU

— Bloomberg (@business) October 8, 2021

And with so much combustible debt scattered across the country, even a small spark can start a wider conflagration. Firefighting by financial regulators can only mitigate the problem for so long.

Fundamentally, China’s unbalanced financial system needs a clear-out of bad debts before it can operate without the risk of explosion. And what’s more, if its domestic economy is to stay up and running, it is vital that power and wealth be taken out of the hands of China’s elite and put back into the hands of its ordinary citizens.

James Meadway is an economist and Novara Media columnist.