The Gas Crisis Is Exposing the Lie in Britain’s Decarbonisation Strategy

It's time for the government to break up with natural gas.

by Lauren Van Schaik

11 November 2021

As Boris Johnson apes green statesman at COP26, Britons brace for a cold winter of energy insecurity, exacerbated by the UK’s continued reliance on a precarious fossil fuel economy and a ‘green revolution’ that uses polluting natural gas as a cheat code.

It’s only November, and already stratospheric gas prices mean National Grid is bringing the UK’s mothballed coal-fired power stations back online. Meanwhile, Britain’s poorest households are being forced to decide between heating their homes and buying groceries. The gas crisis is unravelling both the UK’s green credentials and our very economy – and all as we play host to the world.

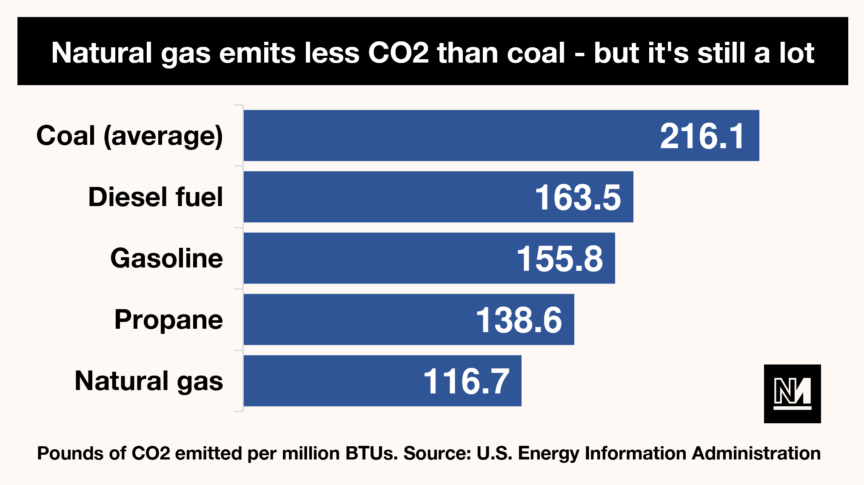

Of course, eradicating fossil fuels from our power, heating and industry would have spared the UK this chaos. But our government has built its decarbonisation gains on natural gas – a fossil fuel that’s cleaner than coal, but still heavily polluting.

Natural gas is also deeply embedded in the government’s future decarbonisation plans – which rely on dirty carbon capture and storage (CCS) and blue hydrogen – thereby guaranteeing the UK is chained to fossil fuel producers and volatile hydrocarbon markets for decades to come.

Spiralling gas prices spell chaos.

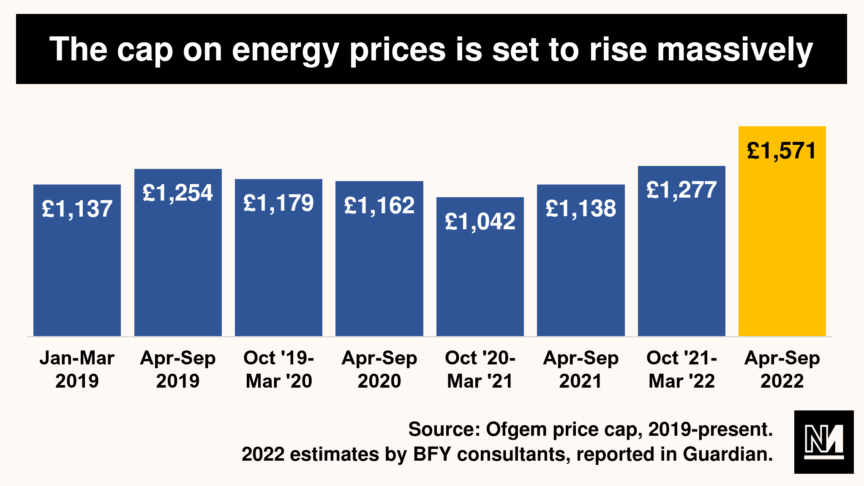

While the direst forecasts of power cuts and three-day work weeks as a result of the crisis — 1970s hardships that the right cites to smear industrial action and state ownership of the energy system – may not come to pass, the UK is guaranteed economic disruption this winter. Energy bills are already the highest they’ve been since 2013, with the price cap slated for an even more punishing £400-600 hike in April.

Meanwhile, 20 energy suppliers have collapsed since August, leaving more than 2m households to be shunted to other firms, often with their fixed-rate tariffs reneged on and bills hiked overnight.

These failed companies also owe hundreds of millions of pounds to their customers and green energy funds — debts that will be distributed across the market, ensuring bills will be high for years to come. Chris O’Shea, the chief executive of Centrica – which owns British Gas, one of the few suppliers likely to survive the crisis – warned a House of Lords select committee last month that households will each pay at least £100 and possibly up to £200 simply to cover the cost of these suppliers failing.

Spiralling energy costs could also push inflation up to five percent by April – according to Bank of England forecasts – and are already contributing to higher prices for everything from food to paper. The crisis may also cost us jobs: manufacturers in energy-intensive sectors, such as steel, ceramics and brickmaking, warn that untenable energy prices could force them to halt production.

For many households in the UK already living on a financial knife-edge, this winter’s disruption will be catastrophic. The National Energy Action charity forecasts that 1.5m more households could slip into fuel poverty in 2022, with a cascade of ill effects, including worsening physical and mental health and increased pressure on the NHS.

Chief Executive of National Energy Action warns further price rises could be coming in the future, pushing more families into fuel poverty. He calls for more help for people in the budget to survive the rising prices. pic.twitter.com/9Urlv7h30T

— Good Morning Britain (@GMB) October 11, 2021

The UK is uniquely vulnerable to overheated gas markets.

The recent explosion in gas prices is not unique to this country, but a global event, with many of its causes external to the UK. The coronavirus pandemic is a major factor: lockdowns paused gas exploration and delayed mine and pipe maintenance, which has strangled supplies in the present.

Reopened economies rebounded quickly, their natural gas demand exceeding forecasts. This was especially true in Asia, where a new appetite for liquified natural gas (because of its slightly greener profile—catching onto the UK’s trick) is drawing tankers away from Europe. Furthermore, last winter was long and frigid across the Northern Hemisphere, depleting gas stores that countries struggled to replenish over the summer. As a result, wholesale gas prices have climbed to record highs in France, Germany, Spain and Italy.

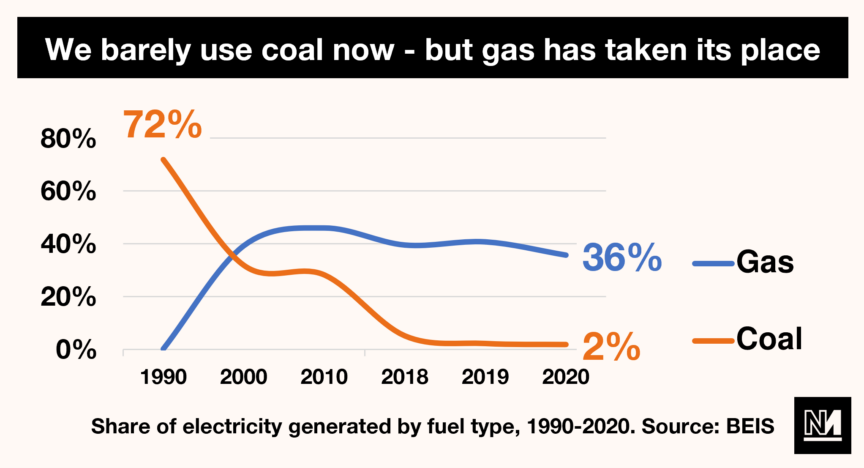

But while the crisis has impacted many countries, the UK is uniquely exposed to it because successive Tory governments piloted a short-sighted decarbonisation path, fixated on easy, headline-grabbing wins, such as eliminating coal from the power grid, and shied away from the more painful challenge of reducing natural gas use in electricity generation, homes and manufacturing.

While UK representatives at COP26 smugly tell the world that our emissions are down 44% since 1990 – the steepest reduction in the G20 – most of these cuts are from replacing coal with more efficient and only marginally cleaner fossil fuel gas in electricity generation. Indeed, while coal’s share of generation plunged from 72% in 1990 to 1.8% last year, gas’ share shot from negligible to 35.7% over that same period.

Gas shortages now mean the UK faces a winter of tight electricity supplies – and to keep the lights on, National Grid has turned to coal-fired power stations. Indeed, far from being phased out, all three of Britain’s remaining coal plants have been running during COP, generating upwards of five percent of our electricity.

UK Prime Minister @BorisJohnson has said he does not want to see more coal in the UK.

When I pressed him on whether his government would take action to stop a proposed coal mine in Cumbria, he demurred: “We’ll do what we’re legally able to do, but this is a planning decision.” pic.twitter.com/j4XSxuNHWv

— Christiane Amanpour (@camanpour) November 2, 2021

One of these stations is Drax in North Yorkshire. Once the third-largest coal plant in Europe, its coal units technically closed to commercial generation in March. However, as a result of the gas price spike, it’s now been brought out of semi-retirement, with the plant likely set to burn coal beyond its intended September 2022 hard stop date.

Underinvestment in electric heat leaves the UK out in the cold.

A top-down overhaul of electricity generation was always low-hanging fruit. Transforming heat on the other hand requires costly intervention in every home – an investment a string of Tory governments have been unwilling to make. True to an ideology that pins the blame for climate change on individual choices, the Conservatives have relied on households themselves funding new, low-carbon heating systems.

But with incomes stretched and low-carbon heat pumps costing anywhere between £6,000 and £18,000, few Britons have made that investment. Indeed, recent figures from Greenpeace reveal the UK sells the fewest heat pumps per capita of 21 European countries; proportionately, we’ve installed five times fewer than Lithuania and 30 times fewer than Estonia.

To address this gap, the government announced last month that starting in April 2022 it will offer households in England and Wales £5,000 grants to offset the cost of installing electric heating systems. This sounds promising, however, the scheme will fund only 90,000 heat pump installations over three years – a drop in the ocean when 25m gas boilers need to be replaced, and the prime minister’s own Ten Point Plan calls for 600,000 annual installations by 2028.

It could also turn out to be just as shambolic as its predecessors, including the Green Homes Grant (GHG), which was advertised at its launch last September as a key engine of the green recovery from the coronavirus crisis.

GHG was intended to install energy-efficiency measures including heat pumps in 600,000 properties. It was greeted with public enthusiasm: in a YouGov poll, 62% of homeowners expressed interest in the vouchers of up to £5,000 to cover two-thirds of the cost of eco-friendly home upgrades. However, its implementation was “nothing short of disastrous”, a parliamentary select committee found. A costly, time-consuming accreditation process dissuaded tradespeople from participating, and applicants struggled to find local builders to do the work. Payments through the scheme were then so delayed that a third of participating tradespeople said the viability of their businesses was threatened, according to research from industry associations. GHG was ultimately axed a year early and having delivered just 41,300 upgrades.

Another policy failure -UK govt scraps £1.5bn green homes grant after six months.

Is there anything that this govt can organise – PPE, test/trace; crackdown on bank frauds, money laundering, tax avoidance, poverty, inequality; improve nurses’ pay ……https://t.co/js1dBOU3rB— Prem Sikka (@premnsikka) March 28, 2021

85% of UK homes continue to use gas – among the highest in Europe and an increasingly costly, tenuous way to keep warm. The government is also still digging the hole, given that it will permit homebuilders to install gas boilers in new properties until 2025 and not outright restrict the sale of all gas boilers until 2035.

A disingenuous approach to decarbonisation.

Despite this autumn’s turmoil, there is little credible sign the government wants to break this reliance on natural gas – although it attempts to disguise this.

Last month, ministers accelerated the target date for a zero-carbon electricity grid from 2050 to 2035. Promoting the revised timeline, Johnson spoke of the “advantage” of not being “dependent on hydrocarbons coming from overseas… the risk that poses for people’s pockets”. Significantly, however, this zero-carbon grid won’t be fossil fuel-free; in the same press release, the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy vowed to “double down” on investment in a “new generation of technologies… including Carbon Capture and Storage [CCS]”, and said that gas generation will “play a critical role in keeping the UK electricity system secure and stable”.

Given all this enthusiasm about CCS – last year’s spending review included £1bn in public investment for its development – you’d be shocked to learn that the technology is largely a pipe dream. Just 26 CCS plants operate worldwide, often at colossal expense, and with real-life carbon capture rates as low as 65%.

Carbon Capture and Storage is the latest industry greenwashing tactic that risks prolonging the life of the oil and gas.

CCS is a dangerous distraction from the real work of fairly transitioning away from fossil fuels & boosting renewable energy. https://t.co/YYJBlejpTZ

— Friends of the Earth Scotland 🌎 (@FoEScot) July 10, 2021

Under government plans, CCS may also be deployed to spuriously clean up the production of hydrogen from natural gas. Hydrogen gas is mooted as a clean alternative to natural gas in heating, cooking, and heavy industry. While it can be produced cleanly with the renewables-powered electrolysis of water (‘green hydrogen’), the government has adopted a “twin-track” hydrogen strategy that also supports the dirtier ‘blue hydrogen’ created from natural gas, with emissions theoretically contained by CCS.

While blue hydrogen is heavily promoted as environmentally friendly by fossil fuel companies, such as BP and Equinor, it’s actually another highly polluting shortcut – and one that will allow these firms to continue drilling for fossil fuels for decades. Friends of the Earth Scotland estimates that using blue hydrogen as a replacement for natural gas in the UK would annually produce 6-8m tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, the equivalent of running 1.5m petrol cars.

You know where Blue hydrogen comes from? Fracked gas. Blue hydrogen has worse emissions than coal, locks in more powerful climate destruction than what we’re doing now.

Blue is bad. (Grey too)

Guess which one bipar bill finances? Blue. So we need to mitigate that BIF alone harm

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) October 28, 2021

Far from being a panacea, CCS is a duplicitous way to continue drilling for fossil fuels, and burning gas and dubiously carbon-neutral (but heavily subsidised as renewable) biomass. Indeed, heavy investment in CCS is typical of the Tories’ lurching, disingenuous approach to decarbonisation.

It’s this approach that has led to freezing homes, ballooning energy bills and spiralling prices this year. These are the immediate effects of fossil fuel dependence, felt even in the relatively comfortable UK. Climate catastrophes like famines, rising sea levels and wildfires still seem remote here – the peril of the Global South and holiday destinations. But with fossil fuel dependence impacting both our wallets and our thermostats, more of us may start to see through the Tories’ counterfeit decarbonisation strategy.

If the government was actually serious about unshackling the UK from hydrocarbon markets, it would implement a national retrofit strategy for homes, directly funding heat pumps and insulation for many households. It would also halt new gas boiler installations immediately, not years in the future; and spend the money allocated for fanciful carbon capture schemes on renewables. Until then, this winter’s chaos might become routine.

Lauren Van Schaik is a London-based journalist and writer.